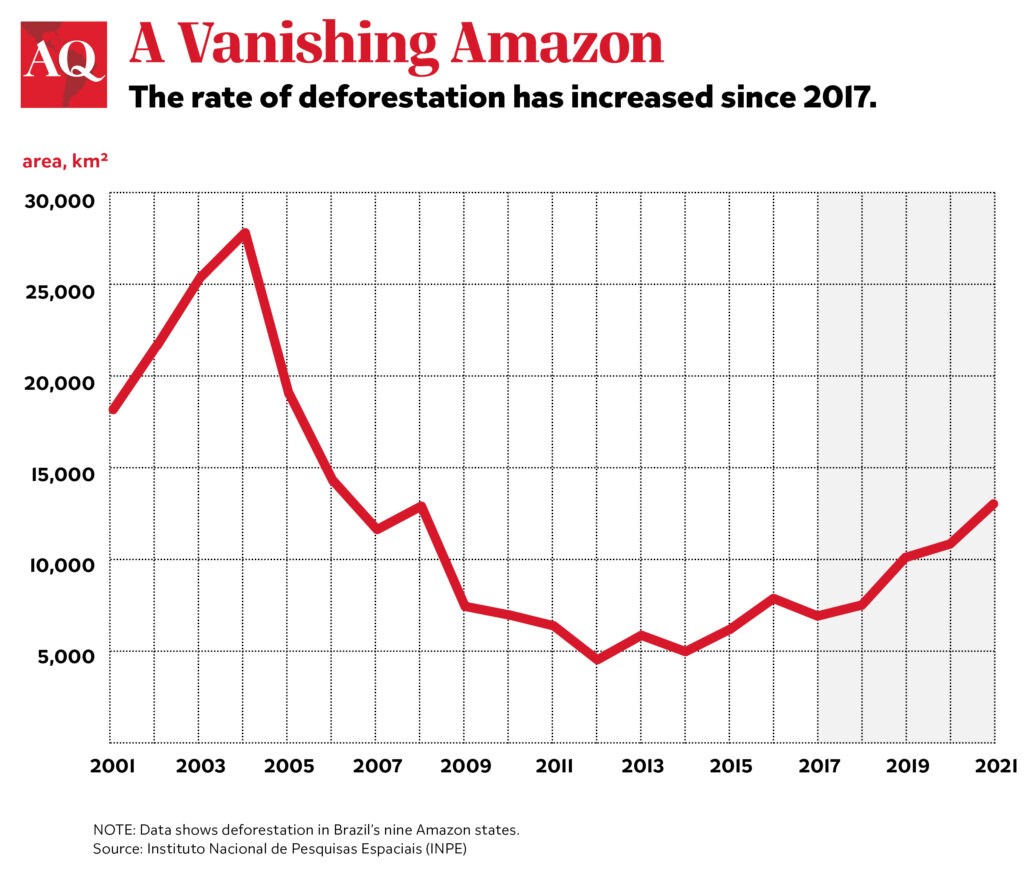

As the United Nations Climate Summit takes place in Egypt, climate issues are again in the global spotlight. And in Brazil, the incoming administration of President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva looks set to restore a focus on environmental concerns like global climate change, food security and deforestation.

But Lula can’t fight Brazil’s deforestation all by himself: He will need the support of the international community. Now it’s time for U.S. policymakers to consider how they can best support Brazil moving forward. That means seeking international support for policy that enhances sustainable development in Brazil while increasing the costs for those responsible for deforestation. And one crucial area of action is trade policy, where the U.S. can take action now to combat deforestation-linked trade.

This won’t be easy and has immediate political risks, as large segments of Brazilian society and major industries, particularly in the north, continue to support Bolsonaro’s slash-and-burn approach to the development of the Amazon region.

But U.S. policymakers can draw inspiration from two pieces of legislation in the United States and France to lead the private sector in the right direction, as well as encouraging other important state actors, such as China, to ratchet up their actions to end the trade of deforestation-linked commodities.

The first is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which prohibits citizens and entities from bribing foreign government officials to benefit their business interests. The acquisition of illegally produced commodities driving deforestation by U.S. companies may not necessarily require the payment of bribes, but it nevertheless involves undue advantage and criminal intent by disregarding local legislation that is meant to protect the environment. The FCPA could become a powerful tool to more closely monitor and address environmental crime and damage, especially relating to deforestation-linked commodities and trade.

The second example, involves a law passed in 2017 by the French government requiring companies with more than 5,000 employees to identify risks and prevent serious violations of human rights and environmental degradation resulting from business activities abroad. Based on these two precedents, the U.S. Executive and Legislative branches could either extend the reach and impact of the FCPA to include acts of environmental crime abroad, or clarify that the requirements set forth by President Joe Biden’s executive order to combat global deforestation should also apply to trade. Both branches are critical to cleaning up supply chains and underscoring global deforestation as a major priority for both political parties.

The Biden Administration could also consider and advocate for strengthening deforestation-free requirements of large loans provided to Chinese and Brazilian companies by multilateral banks. In this way, rather than waiting for the Chinese government to act more aggressively on deforestation, the U.S. jointly with the United Kingdom and European Union could make sure that their consumers, financial sectors, and companies are doing their part to protect the world’s forests and mitigate climate change. Getting greater support for climate action from China has however remained a difficult, albeit crucial task ahead.

Tackling Deforestation-Linked Trade

The linkages between international trade and deforestation have not gone unnoticed by the international community. France and the United Kingdom introduced new laws to tackle deforestation from agricultural imports, while a similar proposal has been approved by the European Union. In addition to the Biden Administration’s executive order in April 2022 aiming to combat global deforestation, U.S. Congress could also consider a bill on this topic as well. The main objective of these measures in the United States and Europe is to block the market entry of commodities resulting from deforestation and to ensure that the environment is protected in the countries of origin exporting agricultural products.

However, as trade in Brazilian agricultural products has shifted to Asia in recent years, the impact of U.S. and European measures may have a less influential impact. According to Brazil’s Ministry of Agriculture, the value of Brazil’s agricultural exports sold to the European Union, United Kingdom, and United States has declined to only 22% in recent years, whereas China alone is now responsible for 38% as a final destination of Brazil’s agricultural products. For some commodities such as soy, the figure grows even higher, representing 58% in 2021.

However, the U.S. could still deploy influential tools and economic statecraft to impact trade connected to deforestation, specifically as it relates to soy. In 2018, nearly half of the soy exported to China from Brazil was traded by an oligopoly of four large, U.S.-based companies. According to TRASE, the trade with China from those companies was responsible for 37% of the carbon emissions from deforestation linked to Brazilian soy farmers. Since more than 91% of deforestation from soy farms in the Amazon and 45% in the Cerrado do not comply with Brazilian Forest Code, it is clear that the private sector in the U.S. could be doing much more to lower its climate impact by both supporting and respecting local environmental laws.

The U.S. has an important leadership opportunity to transform these negative outcomes by implementing new trade policies that recognize the current climate crisis and role of deforestation. The private sector and environmentally responsible companies should clearly be given priority to operate and benefit from agricultural trade that is based in sustainable development. However, those connected to commodities driving illegal deforestation, exporting or representing trade transactions, or providing the financial backing and investment support, whether directly or via third-party ventures, must stop if we are to have any chance of meeting our climate goals and avoiding catastrophic climate change.

There is still time to act in a concerted effort to support Brazilian development that sees the challenge of climate change and food security as opportunities to create new partnerships and revitalize democratic governance within Latin America. The alternative, to allow the status quo of deforestation to persist, is a squandered moment where environmental degradation will inevitably lead to future instability. To avoid this scenario, U.S. trade policy can and should be revamped in the near-future to tackle deforestation head-on.

—

Rajão is a professor in the Federal University of Minas Gerais and fellow at the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program and Brazil Institute.

Beal is an associate in the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program.