It’s decision time for Chile’s proposed new constitution.

After a year of often contentious drafting, Chile’s constitutional assembly delivered a finished draft of the charter to President Gabriel Boric in a ceremony on July 4. Attention now turns to a September 4 “exit plebiscite,” in which Chileans will vote to determine whether the charter will replace the current 1980 version, written during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

The document is long and complex—running to 388 articles—leaving many Chileans and outside observers alike unclear about its contents and just how thoroughly it would transform Chile’s economy, politics and day-to-day life.

Defenders champion the document’s progress on indigenous rights, social guarantees and decentralization of power, which they say will address society’s demands for a more egalitarian society, following large street protests that swept the country in 2019. Critics allege it is a maximalist, unwieldy and divisive charter that would damage the country’s political stability and economic dynamism of past years. During the last plenary meeting of the assembly in late June, communists exchanged barbs with conservatives and one representative remarked: “We are more divided and radicalized than when we started a year ago.”

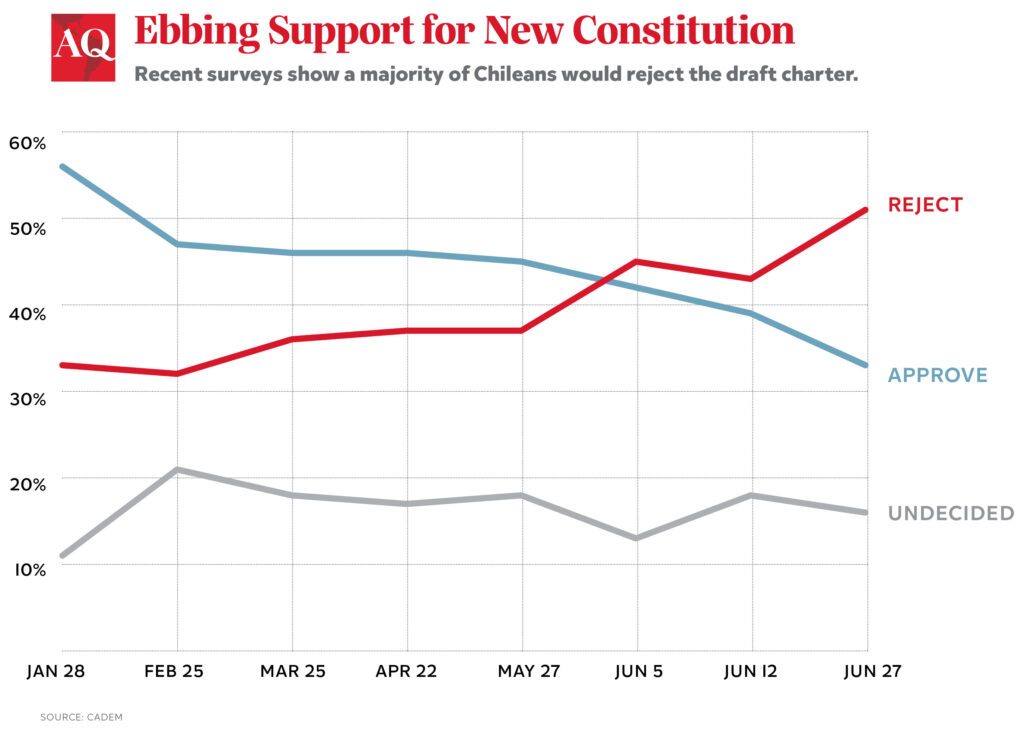

Recent polls suggest the proposed constitution is at risk of being rejected in the plebiscite. If the document is approved, it could take several years to implement all of its provisions, some observers say, due to the need for so-called enabling legislation to turn its provisions into reality. Crucially, it is the current Congress, which is considered more moderate than the constitutional assembly, which would be tasked with that responsibility.

With input from several leading analysts, AQ has produced this overview of seven key points in the proposed constitution, and how they might in practice change Chile if the document is approved.

1. The end of the Senate

The most visible change to Chile’s constitutional structure is the end of the upper chamber of the legislature, which would be replaced by a “Chamber of Regions.”

The change was motivated by a sense by some drafters that the Chilean Senate is an elitist chamber where reforms tended to stagnate. Many of the constitution’s drafters wanted a single chamber, which could pass legislation more efficiently, while others complained that this would erode checks on power. The resulting compromise was “asymmetric bicameralism”—transforming the Senate into a somewhat diminished body representing Chile’s regions.

Javier Couso, professor at Diego Portales University and at Utrecht in the Netherlands, notes that the draft charter provides that the Chamber of Regions must be consulted on changes to the constitution, as well as all tax and budgetary matters.

But in practice that would still be less influence than the Senate currently has. “Whoever wins both the executive and the (lower) house would have a lot of power,” said Rodrigo Delaveau, a lecturer in law at the University of Chicago.

Some observers worry that having a diminished second chamber would make policy more unstable, leaving the other chamber susceptible to frequent changes in ideological makeup and thus different sets of laws. But others emphasize that countries such as Costa Rica have a unicameral system without destabilizing policymaking.

The plan is to transition slowly away from the current arrangement—the Senate would continue to function until 2026, meaning all but the most recently elected senators would serve out their terms.

2. Decentralization of power

Decentralization is a longstanding demand in Chile, where power is unusually concentrated in the capital despite the country’s spanning 2,600 miles from end to end. (Until 2021, regional governors were appointed by the central government, not elected.) The new constitution draft proposes to deliver on this demand, supplying new powers to regions, communes and indigenous territories.

Some fear for the integrity of the state, wondering if the central state will maintain authority in indigenous areas. This concern is taking shape against a backdrop of a worsening security situation in the heavily indigenous south-central regions of Araucanía and Biobío, where deadly clashes over land rights and extractive use are pitting indigenous groups against forestry and mining companies.

“There is one unitary Chilean state, but there will be certain kinds of autonomy,” Jennifer Piscopo, a professor at Occidental College, told AQ in response to these concerns. She added that “a lot of the details are still going to have to be worked out.”

The idea of powers of taxation for the regions unnerves some, who think of how some Argentine provinces infamously issued their own currency during the 2001 economic crisis, and have since contracted large amounts of debt. But in part for that reason, Couso said, the current draft stipulates that enabling legislation will heavily restrict the conditions under which the regions will be able to take on debt.

3. A socially and environmentally conscious state

The draft document describes Chile as a “social state,” and mentions the state will provide a healthcare service and ensure housing and quality education. Nature is also accorded rights, and new state organs are set to take up the task of protecting it.

It’s a clear move away from the principle of subsidiarity embedded in the current constitution, which provides that the state avoid involvement in realms that the private sector could address instead. That principle’s applications to healthcare and education make the 1980 charter one of the most conservative constitutions in the world.

No one disputes that the draft constitution would increase the size and scope of the Chilean state, as it provides more services to citizens and takes a more prominent regulatory role on environmental issues. But observers disagree about exactly how much it would expand, and how that might affect the country’s business climate, which produced growth rates above the Latin American average for many years.

The answer depends in large part on how the constitution, if passed, is implemented in enabling legislation.

“We’re going to have the creation of a whole bunch of new institutions that are going to be expensive to administer,” said Paula Schmidt, a professor at the University of the Andes, citing fears for the fiscal impact. Others saw the shift as a potential opportunity given an increasing focus on environmental, social and governance issues in investment.

“I think there’s no doubt this will be a less business-friendly environment than what the Chilean entrepreneurs are used to,” said Couso. “But Chile will never be like before the uprising of 2019. That marks a world that ended, and those who are more able to adapt to new circumstances will see that there’s (still) good business opportunities.”

4. Doubts remain over mining

Many investors were relieved after a proposal failed to switch Chile’s current concession model, embedded in the 1980 constitution, to a system of temporary, revocable permits. But the lack of specific language governing mining in the draft charter itself could still mark a sea change in the regulatory environment—although the exact contours will remain unclear pending enabling legislation.

“There’s a general rule (in the current constitution) that every substance or mineral is available for concession and only a few of them are reserved to the state,” said Delaveau. But the draft constitution would leave that to be determined by normal statutes. The concession system might be kept, or might be replaced by revocable permits—and these rules could change as successive legislatures enact different laws, adding uncertainty.

It’s also unclear who will give permission to mine under the new constitution. It might remain the task of the judicial system, as under the current constitution; or it might be done by new administrative organs of the state.

One specific change is in the terms of compensation for expropriations. The current constitution specifies the “actual damage”—the market value, more or less—as the standard for setting the amount of compensation, while the new draft would change this to a “fair price,” a standard seen as more open to a judge’s discretion, Delaveau told AQ. Unlike the current constitution, there’s no default rule for how compensation should be awarded if the parties can’t come to an agreement.

5. Greater weight to indigenous issues

One aspect of the new constitution that attracted particular attention are provisions dealing with legal and land issues for indigenous people. The new constitution defines Chile as a plurinational state and proposes to consider customary law for indigenous people, which has spurred criticism that it provides for a parallel justice system or special treatment.

This perception could be damaging for the charter’s electoral prospects. Some believe the charter “doesn’t put [indigenous people] in the same group as everyone else, but above,” Schmidt said.

But others emphasized parallels to methods of handing indigenous issues in Canada, New Zealand and Mexico, suggesting the Chilean justice system would retain supremacy.

Language requiring the consultation of indigenous groups on affairs affecting them met with contrasting interpretations. Some say this handed indigenous groups a dangerous veto on a broad range of topics, while others argued it required consultation only on a limited set of issues restrained to indigenous territories. The convention rejected language that aimed to clarify the matter, leaving its implications unclear.

6. Changes to water rights

Chile at present is the only country to declare water private property in its constitution, and the highly privatized water rights system was a lightning rod of protest in 2019. With drought conditions having lasted for more than a decade, the water issue has taken on new urgency as the capital introduces a rationing scheme, lakes have dried up and the use of water by extractive industries like mining and forestry is increasingly controversial.

The new draft constitution declares water rights incomerciables—roughly, “unsellable”—but no one knows precisely what that means, or how it will be put in place legally. “The specialists don’t understand the implications of this,” said Pía Mundaca, a political scientist at the Catholic University of Chile. “It will be one of the topics that we need to organize.”

That creates uncertainty which may affect the economy. “In the absence of understanding how it’s going to work, (companies) may hold off on investment,” said Kathy Barclay, who leads Asesorías KCB. “I think it’s very wide open, particularly on water.” It’s not clear what the exact implications are for the country’s secondary market for water rights.

7. Moving beyond gender parity

The draft constitution’s defenders are quick to argue that most of the provisions in the document are not radical experiments and have precedents in constitutions around the world. But on one point, they’re eager to acknowledge that this document goes further than any other: gender parity. The draft constitution mandates that all public institutions—from ministries to semi-public corporations—have at least 50% of their members be women, meaning men can be a minority, but women cannot. That goes further than laws in places like Mexico that mandate a precise 50-50 parity in the legislature and other state organs.

Some feared that, like indigenous issues, it might shape the document into something that divided Chilean society instead of unifying it. “More women, I’m super in favor of it, but I don’t think establishing constitutional gender parity is (the best way to) get to the objective,” said Schmidt.

But there’s been less public criticism over this aspect than about others, in part because the constitutional convention itself was elected on a gender parity basis. (In fact, some women who would have been elected had to be turned away to meet its 50-50 criterion.)

“Gender parity is the most tested of all the new innovations of this constitution,” said Couso.