This article marks the launch of the fourth edition of the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index produced by the Americas Society/Council of the Americas and Control Risks. Click here to read the 2022 CCC Index report.

Every time somebody declares the anti-corruption efforts in Latin America dead or in retreat, along comes reality to suggest otherwise. Consider last Sunday’s elections in Colombia, where voters ranked corruption the country’s most pressing challenge—ahead of poverty, crime and unemployment. The runner-up ran on the slogan “Don’t steal, don’t lie, don’t cheat and zero impunity.” The winner, Gustavo Petro, also made the issue a centerpiece of his platform, vowing to create an independent, UN-sponsored anti-corruption body similar to the one that led groundbreaking investigations in Guatemala last decade, among other initiatives.

Indeed, we see variations on this story throughout much of Latin America today. Despite the widely held view that corruption has been relegated to a second-tier issue by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising inflation and the continued backlash against investigations in countries such as Brazil, anti-graft efforts have remained a key element of the region’s politics. Just last week, Peruvian President Pedro Castillo appeared in front of prosecutors as part of an investigation into whether he led an alleged criminal conspiracy involving bribes for public works contracts (Castillo denies wrongdoing). Ecuador’s President Guillermo Lasso issued a decree in May creating an Anti-Corruption Secretariat that will be a Cabinet-level position. Corruption is also expected to be a major issue in elections in Argentina and Paraguay next year.

This continued mobilization forms the backdrop for the 4th annual edition of the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index, released Wednesday. Rather than measuring perceived levels of corruption as other studies do, the CCC Index evaluates and ranks 15 Latin American countries based on their ability to detect, punish and prevent corruption. The index, which is jointly published by Control Risks and the Americas Society/Council of the Americas (which publishes AQ), draws on publicly available data as well as a proprietary survey that asks in-region experts to assess a variety of factors including the independence of courts, the strength of democratic institutions and the freedom of investigative journalists.

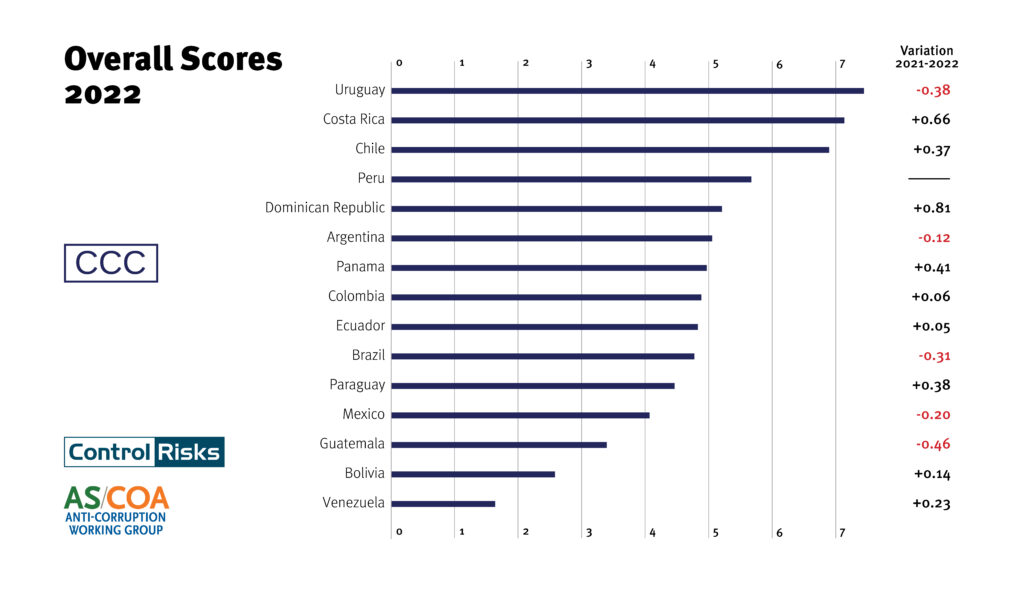

This year’s index paints a mixed picture, in which some Latin American countries made progress in improving the anti-corruption environment, while others, including the region’s two largest countries Mexico and Brazil, saw new setbacks for key institutions.

Indeed, both Mexico and Brazil have seen significant cumulative declines in their scores since the index was first launched in 2019–by 13% and 22%, respectively. Presidents Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Jair Bolsonaro, while different in many ways, have in practice both taken steps to undermine independent institutions that are key to preventing graft, preferring instead to emphasize what they bill as their own personal rectitude. In Brazil, continued scrutiny of the perceived abuses of the Lava Jato investigation in the late 2010s, and the political revival of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-10) after corruption charges against him were overturned or dropped, have made anti-graft efforts a comparatively minor issue in the campaign for October’s presidential election. Guatemala showed the biggest decline in score, as several prominent anti-corruption figures fled the country, alleging they were being persecuted for their work.

Elsewhere, though, there were stories of resilience and progress. Peru retained its relatively high ranking, as courts and investigators continued to show independence even after investigating multiple presidents in recent years, including the current one. The Dominican Republic showed the biggest increase in its score, up 18% since 2021, as President Luis Abinader proposed a law to promote greater transparency in public contracts, among other reforms. Uruguay remained the country with the highest overall score in the ranking, despite a relatively minor decline, followed by Costa Rica and Chile. Although Argentina again scored below the regional average in key variables like the independence and efficiency of anti-corruption agencies, its strong performance on indicators measuring the strength of civil society, investigative journalism and overall quality of democracy allowed it to retain a relatively solid position in the overall ranking.

It’s interesting to examine why the issue has refused to go away. Some have argued that the focus on anti-corruption in Latin America is destructive and pointless, contending that it tends to produce unqualified outsider candidates who, once elected, make little progress against graft, and often end up undermining democracy as a whole. Some point to Bolsonaro as an example. But this strikes us as an overly fatalistic view that unfairly discounts the possibility of progress in Latin America. It would be a disservice to ignore the efforts of prosecutors, judges and others who have successfully strengthened institutions and the rule of law since democracy returned to most of the region in the 1970s and 1980s. Many in the current generation are bravely pushing back against the authoritarian winds blowing again in some countries today. And they retain the support of the general public in many places.

Indeed, the same factors that led to the rise of the anti-corruption push in the mid-2010s–the spread of democracy, the changing values of a rising middle class, and the prominence of social media–are still present today. Perhaps we will look back on the COVID-19 pandemic as a temporary disruption in the anti-corruption trend, rather than a permanent change. Even in Brazil, where there are some disturbing signs of graft schemes resurfacing, and some companies are more closely scrutinizing spending on compliance programs and teams, the overall business and regulatory environments are still clearly less tolerant of corruption than they were prior to Lava Jato. As so often in Latin America, progress can be halting, and even experience extended periods of retreat. But progress does occur–and politicians, executives and others forget that at their own peril.

__

Aalbers is a partner at Control Risks

Winter is the vice president for policy at AS/COA and editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly

Sweigart is a policy manager at AS/COA and an editor at Americas Quarterly