MEXICO CITY — Inside Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s decision not to attend last week’s Summit of the Americas has sparked a flurry of hand-wringing over the future of the country’s relationship with the United States. Will President Joe Biden retaliate against the perceived slight? Would business and commercial ties between the two neighbors ultimately suffer?

Some analysts argued the repercussions have already begun: U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken denounced violence against Mexican journalists on June 7, just a day after AMLO communicated his final decision not to travel to Los Angeles. The U.S. Trade Representative, Katherine Tai, issued a complaint against Mexico regarding labor rights two days afterward.

But such concerns suggest an anachronistic, zero-sum vision of the bilateral relationship. The reality is that in today’s changing world, the United States and Mexico are so deeply interconnected that they can disagree and even criticize each other without causing a major, enduring crisis.

This is partly due to a global dynamic that goes well beyond Mexico. As many other analysts have observed, the world order is currently being reconfigured in a way that is more multipolar and reflects a relative decline in U.S. power. We saw this most notoriously during the Donald Trump administration and its move away from traditional U.S. leadership, especially during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the U.S.-Mexico relationship has survived—and even thrived—during this otherwise difficult period. With Trump in office in the U.S., when AMLO won the Mexican presidency in July 2018, many observers anticipated a very tense relationship and even a rupture. But AMLO’s pragmatism prevailed, and the administrations negotiated a new trade agreement, the USMCA, while the two presidents maintained a friendly public relationship. This has not changed with Joe Biden’s administration. Perhaps the main novelty is that U.S. Ambassador Ken Salazar maintains a more direct and frequent dialogue with the president than his predecessor. All of this should put to rest the traditional notion that Mexico should always retreat in its dealings with the United States, or that Washington always wins by trying to impose its will.

There are signs that, in practice, a more mature and stable relationship is already taking root. Blinken was not the first U.S. secretary of state to speak up about security challenges in Mexico—Hillary Clinton even spoke in 2010 of Mexican organized crime groups as an “insurgency,” and compared the country’s security situation to that of Colombia. On trade, meanwhile, Tai’s complaint represented the fourth such intervention by the U.S. through channels established through the mechanisms of the USMCA free trade agreement. It was planned in advance and would have gone out whether or not AMLO had decided to attend the summit—meaning it wasn’t intended as a reprimand.

Salazar seemed to sum up Washington’s position in an interview on June 16. “I’m not always in agreement with President López Obrador,” he said. “But we have good dialogue.”

And in fact, Mexico has long shown that it can distance itself from the U.S. on multilateral issues without harming the bilateral relationship. For example, in 2003, Mexico departed from the U.S. stance on the war on terrorism and the invasion of Iraq, but it cooperated on bilateral issues, such as migration and combating drug trafficking. In a recent interview, Mexican Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard mentioned Mexico’s 1962 vote against expelling Cuba from the OAS, arguing that there have long been differences between the U.S. and Mexico on the subject of the island nation. He told me something similar in an interview for N Más on June 15.

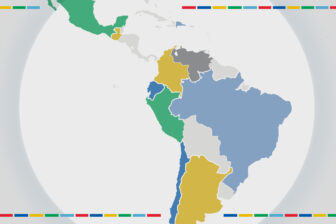

Now, Mexico has questioned the U.S. position on excluding countries from the summit—adhering to what Ebrard, who did attend the gathering in Los Angeles, calls the “López Obrador Doctrine”: a recognition that the balance of power has changed in the Americas, with more countries embracing leftist governments and the rhetoric of national sovereignty, and especially that U.S. influence, both globally and hemispherically, is in decline or at least changing.

But Mexico is still cooperating closely with the U.S. on issues like migration. For example, despite the Mexican president’s absence from the hemispheric gathering, the major announcement on migration launched there contained commitments by Mexico to create a new temporary labor program, expand existing border worker programs and integrate 20,000 refugees into its labor market over the next three years. In fact, AMLO’s government is paying a domestic political cost for stopping migrant caravans, retaining thousands of migrants and policing Mexico’s borders with Central America and with the U.S.

Nonetheless, Mexico’s government is also advancing its soft power agenda for Central America. At the summit, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris announced $1.9 billion in private sector investment in Central America in hopes of combating the root causes of migration. Ebrard has repeatedly asked for more American investment in the region and has made similar requests to his European counterparts.

Two big signs that the U.S.-Mexico relationship remains healthy and productive are, first, the next meeting of the “Three Amigos” (Mexico, Canada and the U.S.), which is to be held in Mexico at the end of 2022, and second, AMLO’s upcoming visit to Biden in Washington in July. In fact, the latter was one of the first things Marcelo Ebrard highlighted on his Twitter feed after arriving at the summit. “Talking about the next meeting between Presidents López Obrador and Biden in Washington,” he wrote on June 8, seeming to convey Mexico’s eagerness to look past the summit and focus on the next milestone.

AMLO will be hoping to win public embrace from Biden, which would help him make the case that the most important relationship for Mexico in the world is alive and kicking, and that the U.S. sees Mexico as a partner and equal rather than its “back patio.” AMLO is also looking for more trade, investment and better treatment of Mexican migrants who are already in the U.S.

U.S. observers of Mexico who claim that Biden looks weak by “rewarding” AMLO with a visit should ask themselves who they would rather have as chief mediator between the U.S. on one side and Venezuela, Cuba, Bolivia and other “rogue” governments in the region on the other. On both sides of the border, there should be an acknowledgment that, for both countries, no other relationship in the hemisphere is as important. And finally, AMLO’s visit to Washington, D.C. before the midterm elections in November could help Democrats with Latino voters in the border states. (Of course, Florida is a different story.)

What is clear is that if skipping the summit represented a real disagreement between the U.S. and Mexico, it’s a disagreement in the context of a broad, close and complicated relationship that features more than enough cooperation to keep it moving along.