This article has been updated.

Standing in front of a vast field in Argentina’s Chaco province, President Alberto Fernández greeted the crowd with an enormous smile: “Good morning, amigos, amigas y amigues!” Fernández’s use of the gender-neutral word amigues (friends) is an example of inclusive language, which is increasingly becoming a hot-button issue in the so-called culture wars raging throughout much of Latin America.

Young, left-leaning Gen-Z activists have been spearheading the movement for inclusive language—like the use of phrases such as “todos, todas y todes”—to, they say, stop language from marginalizing women and nonbinary people. This kind of language has been discussed in progressive circles since the feminist movements of the 1970s, but its current use came into vogue during the 2018 pro-choice protests in Argentina.

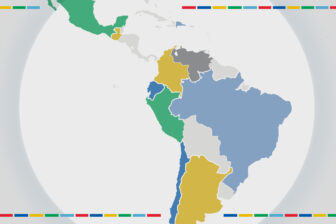

Now, it has swept across the region and into politics, often brandished by politicians on the left and pilloried by those on the right. While the general public frequently shrugs at such controversies, they have still proven a tempting wedge issue at a time when many politicians are eager to deflect attention from rising inflation, stagnant economic growth and other pressing challenges.

In March, for example, a social media firestorm ensued after Colombian vice-presidential candidate Francia Márquez used gender-neutral language in her first remarks as Gustavo Petro’s running mate.

Congressional representative Margarita Restreppo tweeted, “Mayores y mayoras, nadies y nadias, personas y persones ¡Dios salve a Colombia!” and former representative Álvaro Hernán Prada tweeted in Spanish, “They do not know how to speak, they were not taught Spanish … they’re damaging the language.”

Other less strident critics brush off gender-neutral language as nothing more than linguistically incorrect political posturing. The Real Academia Española has repeatedly dismissed it, and the RAE’s director recently called the current push political nonsense. He said the RAE has encouraged the evolution of more inclusive language in the past—by changing, for example, the definition of words like jueza from “a judge’s wife” to “a female judge”—but that the new asks are “foolishness.”

Other critics are painting the use of inclusive language in public settings as part of a large-scale project of ideological indoctrination into pro-LGBTQ “ideologies.” Schools have become a major flashpoint. When a school in Porto Alegre, Brazil, sent students home with gender-neutral texts, some parents complained to school officials and local politicians, and right-leaning pundits helped amplify the event.

Across Brazil, at least 34 state-level bills have cropped up that would restrict the use of gender-neutral language in schools. “There’s a clear political strategy by conservative political leadership [in Brazil] to capitalize on this issue,” said University of São Paulo political science professor Rafael Cortez. He added that right-leaning politicians seize on identity issues like inclusive language to win votes from the rapidly growing, socially conservative evangelical electorate. President Jair Bolsonaro has made his position on the issue clear, declaring in front of the presidential palace that “the gays’ gender-neutral language” is “messing up our kids.” He said, “it damages young people… [making them] interested in those things.”

Similar bills focused on education have appeared across the region. In Uruguay, the far-right Cabildo Abierto proposed a bill that would ban inclusive language in the classroom, and in Nuevo León state in Mexico, a state bill would ban the use of inclusive language within the educational code.

While most relevant legislation in the region restricts rather than encourages the use of inclusive language, Argentina passed a law in 2021 that requires public media—and incentivizes private media—to conform with a series of guidelines meant to establish equity in gender and sexual diversity representation in audiovisual media. The guidelines include the “promotion of the use of inclusive language.” Compliant companies would receive an “equity certificate,” while non-compliance could lead to reduced access to publicity or scheduling from public entities.

The legislation attracted harsh criticism. For Argentine libertarian Javier Milei, “There’s no reason why the state has to put this oppressive boot on my head and force me to use something that even the Real Academia doesn’t accept.”

Yet despite the legislative sparring, polling in Argentina suggests that most people either vaguely favor inclusive language or don’t care at all. This includes even progressives and gender activists. “Today, the discussion [in progressive circles] is more focused on the acquisition of concrete rights, like being able to move freely and having greater equality for trans people, lesbian people [and] the LGBTQ+ collective,” said Gonzalo Olivares, an adjunct professor in sociology at the University of Buenos Aires and a consultant for Argentina’s Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity. “The debate over language just isn’t a priority right now, especially considering the very poor socioeconomic conditions the country is experiencing,” he said.

Cortez, of Brazil, pointed to a similar dynamic. “We cannot deny that step by step these new ideas are impacting the electoral arena … [but] issues like economics, unemployment and crime will still dominate this year’s elections.” He added that media outlets and politicians are giving inclusive language disproportionate attention, considering that Brazilians are much more concerned with a range of other issues.

As the debate over gender-neutral language spreads across borders, one constant remains: politicians and pundits seem more interested than the public.

This article was updated to remove a quote from a Colombian comedy group.

—

González Camaño is an editorial assistant at AQ, specializing in the cultural and ecological politics of the Southern Cone.

Brown is an editor and production manager at AQ.