BUENOS AIRES – As a candidate for president in 2019, Alberto Fernández referred often to Argentina’s economic crisis of the early 2000s. He placed himself at the center of the country’s recovery in 2003 (he was cabinet chief at the time), but tended to make one crucial edit: The critical and prolific 2002 – the key turning point of the crisis – was swept under the rug.

Twenty years on, the legacy of that tumultuous year could hardly be more relevant. But Fernández, now president, appears again to be drawing the wrong lessons. Despite touting a supposed economic recovery from the pandemic and the difficulties that preceded it, the government’s approach instead is setting the country back on a path to decline. It is never too late to learn from the past.

An accidental model

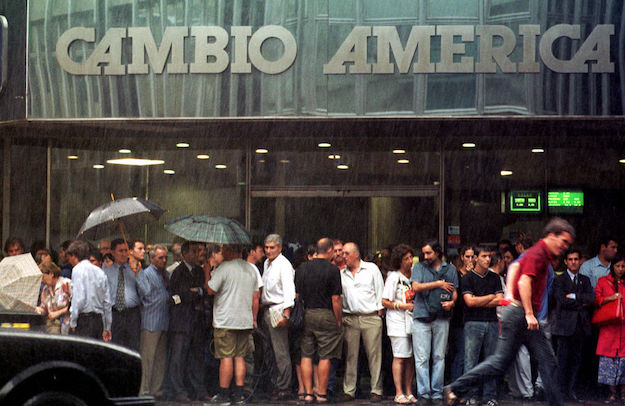

At about this time of year in 2002, a select group of government economists was meeting on weekends in Buenos Aires to plan for the day after the demise of Argentina’s 10-year-old currency board. This fixed exchange rate regime, under which the central bank could print money only in exchange for international reserves, had unwittingly led to a crisis of mounting unemployment and poverty, disgruntled depositors, collapsing banks, and spiraling exchange rate pressures. Weekends offered an illusory pause to the daily emergency – the only opportunity to prepare for anything beyond the next day’s crisis.

The semblance of a plan that grew out of these meetings looks, in hindsight, more deliberate than it actually was. In reality, the government’s reaction consisted of a mix of desperate defensive measures to contain a tsunami: a devaluation coupled with export taxes, a forced conversion of domestic dollar debts at the previous one-to-one parity, exchange and capital controls, a freeze on utility rates, tight monetary policy and a heavy reliance on public transfers as a Band-Aid for rising poverty.

Some of those measures were inevitable, some were influenced by intense lobbying, some were twisted by political compromise. But with the exception of monetary policy (which became more expansionary in 2003 and remained so for a decade), the consequences of the measures taken in those heated days of 2002 remain key features of Argentina’s economy today. Firms are still underleveraged, utilities continue to be subsidized, banks are de-dollarized and export taxes are a key source of foreign exchange.

Then and now

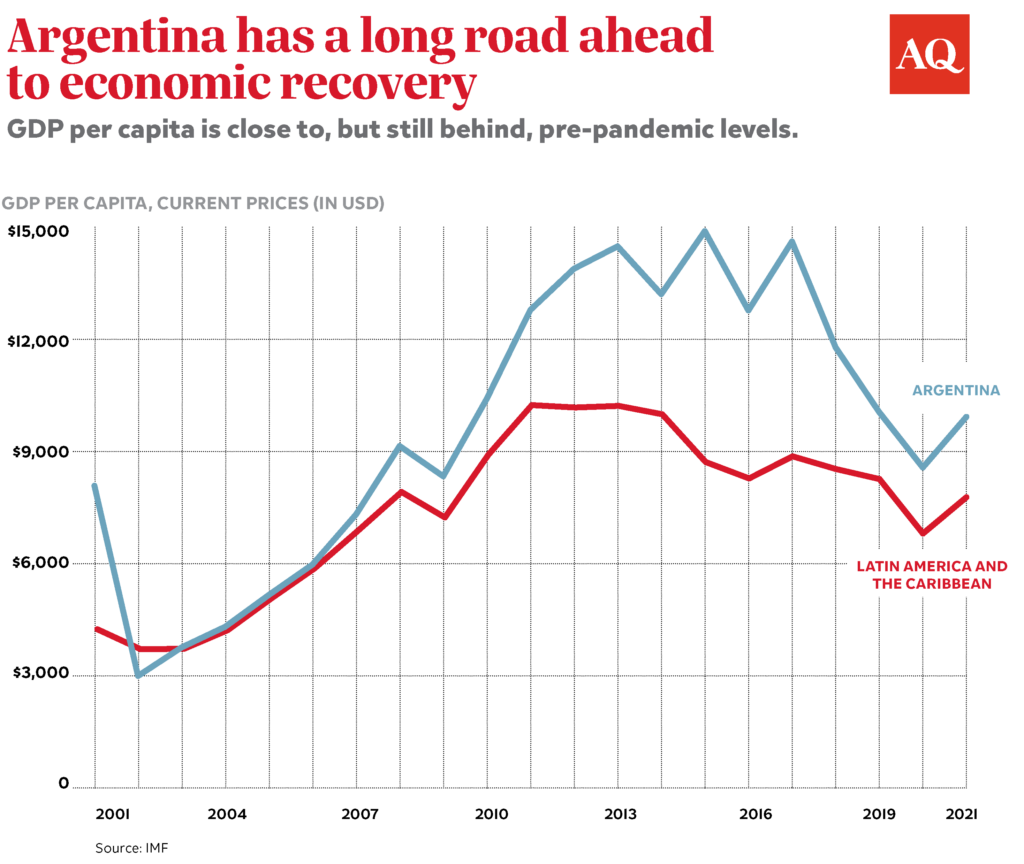

What does this mean for Argentina’s post-COVID recovery? For starters, a careful reexamination of the legacy of 2002 puts the government’s claims of a miraculous recovery from the pandemic on shakier ground.

Today the official line reads more or less like this: Despite a mess inherited in 2019 from the previous administration, the Fernández government managed a rebound in growth, employment and investment to pre-crisis levels while improving public finances thanks to dynamic economic activity, higher and more progressive tax rates on wealth and corporate income, and a successful debt exchange in 2020.

The most recently available figures, however, tell a more complicated story. Exports are still behind their corresponding 2019 numbers – with the exception of primary exports, which in 2021 benefited from a large backlog but are likely to decline in 2022. Imports outpaced exports because producers hurried to buy capital and intermediate goods at a subsidized exchange rate – at the expense of rapidly falling international reserves that in turn generate currency risk and capital flight. GDP is still yet to reach its pre-COVID mark; by year-end 2021 it likely recovered pandemic losses, as most other countries in the region did, but remained below its 2018 peak (Argentina’s crisis preceded COVID by two years). These figures look slightly worse when measured in per capita terms.

Argentina’s rebound has also been uneven. It has centered in sectors such as construction (a dollar substitute for exchange controls), or manufacturing such as cars, clothing and electronics, which are shielded from external competition by import barriers, and by a large premium between the official and the free exchange rate. While this premium may partly reflect speculative savers moving away from the peso, it is also fueled by a deliberate appreciation of the peso to repress (or, rather, postpone) inflation. This exchange rate misalignment, coupled with export taxes and surrender requirements (the obligation to sell export dollars), is already crushing one of the most competitive sectors of the economy: knowledge-based services.

Regarding the “improving fiscal finances,” a quick look at the composition and evolution of spending in 2021 shows that the lower primary deficit (an expected 2.5% of GDP, below initial official forecasts of around 4%) was reached mainly thanks to inflation that rose from 36% in 2020 to 51% in 2021. Because pensions and social transfers are indexed to past inflation and wages, they fall in real terms whenever inflation is high and accelerating (because past inflation is below current inflation). Thus, a decline in social spending partially offset an increase in utility subsidies to middle- and high-income households –hardly a progressive policy mix.

Sadly, this accounting alchemy cuts both ways. Fiscal spending increases in real terms if inflation decelerates and declines. There is little chance that this will be a factor in 2022: To accommodate IMF demands, the government will need to reduce utility subsidies and foreign exchange intervention, relaxing the two remaining inflation anchors. But sooner or later, inflation will have to come down and, in that event, its fiscal dividends will need to be replaced by some bona fide fiscal consolidation.

An elusive miracle

On the 20th anniversary of the 2002 crisis, there has never been a better time for the administration to turn to the past for some perspective on the country’s current predicament.

Perhaps the greatest misunderstanding of Argentina’s quick post-crisis rebound in 2002 is the belief that it was set off by the devaluation, via growing exports and more dynamic import substitution. Whereas the latter may have played a role, export volumes actually grew more slowly than under the currency board, and the global commodity price boom was still incipient when output hit bottom in 2002.

Instead, the main driver of recovery came from an unexpected – and politically unappealing – source: businesses. As it turned out, the crisis resolution package, by easing corporate debts (with the peso conversion) and operating costs (with subsidized utilities and depressed real wages), transferred public and private income to firms’ internal funds, which were reinvested domestically. This explains why investment revived even in the absence of a working financial sector. In turn, growth sped up job recovery and poverty reduction – and, together with new taxes and a commodity boom, created the fiscal and external surpluses that were used up in the fiscal spending spree of the late 2000s.

So it was not export-driven growth, as some observers imagined when recommending the “Argentina solution” to the euro crisis, that pulled the country out of trouble. Nor was it a state-driven Keynesian push, as some in the government may be inclined to imagine today. Another still-relevant feature of the post-2002 environment is the fact that the public sector is broke and, despite a “successful” debt exchange, excluded from international capital markets as if it were still in default.

The ideologically ambiguous nature of an inclusive recovery largely triggered by a regressive transfer to the private sector makes this version of Argentina’s accidental 2002 miracle somewhat less immediately attractive, albeit more real and more relevant to current conditions. While growth may not trickle down enough in normal times, private investment and growth may be the only option for recovery when the state runs out of resources.

The Fernández government seems divided – almost self-contradictory – on this front: it calls for more exports and investment behind closed doors, but continues to squeeze the private sector to fund an illusory consumption-driven recovery, including through inexplicable (and hardly green) subsidies on gas and electricity. It is also on the verge of extending its heavy hand to private activities, notably through regulation of the airline industry and its national airline management.

If the administration fails to take note of the real lessons of the past, it will prevent the kind of post-2002 recovery it hopes to emulate, deepening a crisis that has already been going on for too long.