This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the battle over fake news

A man washes up on a Mexican shore, dressed in 16th-century Spanish attire. Seconds later, an emblematic metal helmet with a flat brim washes up next to him: He is a conquistador. But as he begins to walk, he is confronted with contemporary scenery, signaled by a broken plastic cup. He is lost in time, finding himself unexpectedly in 21st-century Mexico, 499 years after the fall of the great Aztec capital Tenochtitlán.

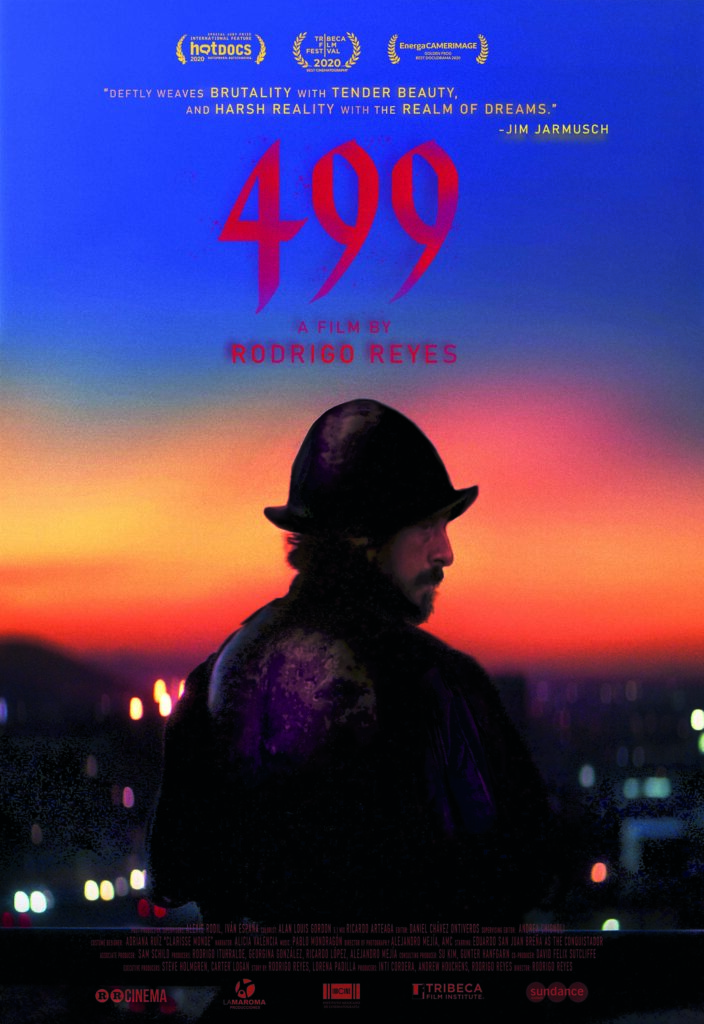

A fictitious, anachronistic conquistador faces real, unscripted people in this one-of-a-kind documentary hybrid film. Director Rodrigo Reyes uses every tool in the cinematographic toolbox to confront the viewer with a harsh reality: Almost half a millennium later, the Spanish conquest of Mexico is not over. As the conquistador retraces his steps from the coast of Veracruz through the Sierra Madre to Tenochtitlán, he encounters people and listens to their stories, muted, because his job now is to listen.

In his journey through a country experiencing historically high homicide rates—29 per 100,000 people—we see his defiant thoughts and actions slowly begin to unravel as he comprehends more of the contemporary aftermath of the conquest.

499

Directed by Rodrigo Reyes

Screenplay by Lorena

Padilla and Rodrigo Reyes

Starring Eduardo San Juan

Mexico

AQ Rating: (4/5)

The lost conquistador is at ease interacting with elements of early modern Spanish culture in modern Mexico: bumping into a horse, watching a bullfight or a traditional dance, even glimpsing modern guns (invented after his time but familiar nonetheless). Yet he is confronted with many types of violence experienced by the people he meets: violence against journalists and civilians, indigenous groups, women and girls, as well as displaced Central American migrants. The parallels to violence in 16th-century Mexico are emphasized by his internal dialogue, which guides us through the conquest.

The conquistador serves as a cathartic sounding board to real people telling their stories, an age-old figure of violence who is forced to listen, understand and experience the collective failings of his time. As his journey nears its end, the conquistador literally begins to lose his armor, piece by piece, starting with his helmet. He finally understands why he is here and why he’ll never go back to his own time. Try as he might, his penance is not enough. He is alive and well now, and will continue to be as much a part of 21st-century Mexico as any of the people he meets, just in a new guise.

__

Reina is a former editor and business and production manager at AQ