This article was updated on June 4

In 1532, in Peru’s highland region of Cajamarca, the Spanish invader Francisco Pizarro captured the last Incan emperor, Atahualpa, in a surprise massacre that ensured the empire’s demise.

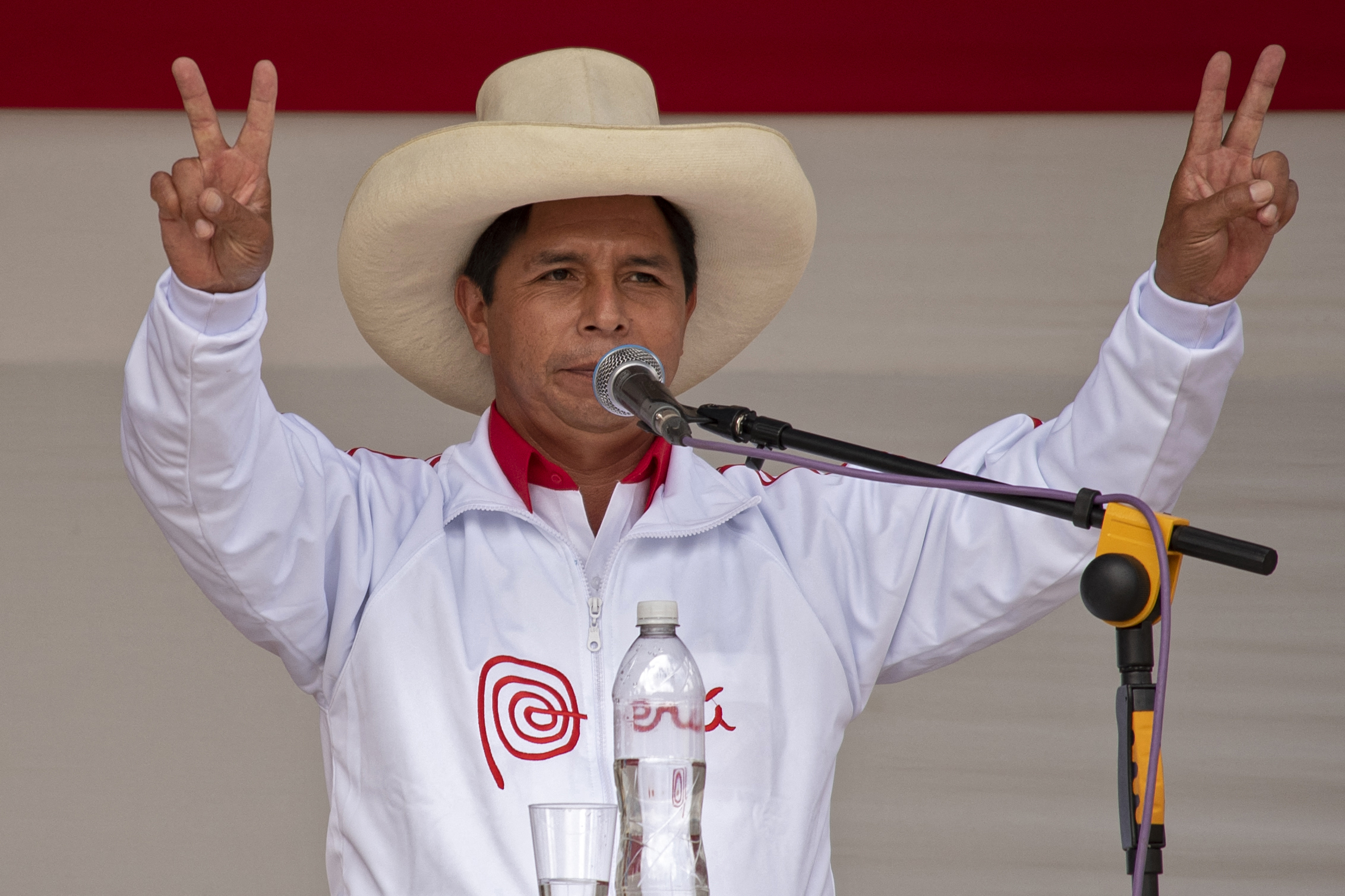

Today, Cajamarca may once again be the site of a historic turning point – as the home of Pedro Castillo, the leftist farmer and schoolteacher who has the edge in a June 6 runoff election to become Peru’s next president. His insurgent campaign has emphasized the vast gap in living standards between Lima and the countryside, a problem with roots going back to the conquest of the 16th century that has often periodically convulsed Peruvian politics ever since.

“This election goes way beyond this year,” said José Ragas, a Peruvian historian currently at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. “It’s an expression of a desire to rethink the historical exclusion and gap between the coastal areas and the highlands.”

A recent cartoon by the political cartoonist Carlos Tovar Samanez made the parallels with the past explicit. In the cartoon, Castillo leads an Incan defense on foot against an imposing Spanish cavalry symbolized by his runoff opponent Keiko Fujimori and the author Mario Vargas Llosa – both symbols of Lima’s conservative elite.

Castillo, whose huayno Andean dance moves at a campaign rally recently went viral, would be just the second president born outside of Lima to be elected since 1956. He finished first on April 11, with just under 19% of the vote nationally, but clearing 50% in three regions in Peru’s mountainous south: Apurimac, Ayacucho and Huancavelica. The regions are representative of what’s often called “Deep Peru,” a world historically and culturally marginalized from a capital where recent governments have been awash with alleged corruption, and where economic gains from industries like mining have not been fully felt.

Peru’s economy grew at an annual average of 4.3% between 1990 and 2019, according to the World Bank, well above the regional average of 2.6% and only slightly less than Latin America’s other “miracle,” Chile. Rural areas benefited greatly too – the share of the population living in poverty in rural areas fell dramatically from 67% to 41% just between 2009 and 2019, according to Peru’s national statistics institute.

But the positive statistics cover up vast differences in quality of life. Life expectancy in Huancavelica, for example, the region where Castillo received his highest share of the vote in the first round, is seven years shorter than in Lima. In Puno, where Castillo received over 47% of the vote, the infant mortality rate is almost three times that of Lima’s.

Historic disparities have been compounded by the health and economic crises brought on by COVID. Peru’s economy shrank 11% in 2020, according to the IMF, the worst in South America besides Venezuela. For months last year Peru had the world’s highest death rate, and a deadly second wave made April its deadliest month. Government aid efforts have been limited by one of the region’s highest rates of labor informality. Meanwhile, less than 3% of Peruvians have received a dose of a vaccine, according to Our World in Data.

“The pandemic and the rise in poverty provided the social conditions for a historic sentiment against the status quo to be expressed in an overwhelming way,” said Gonzalo Banda, a professor of social policy at the Catholic University of Santa María in Arequipa.

Peruvian history has long been shaped by a geographical and often racial divide. The country has elected Lima-born presidents in 11 out of the 18 democratic elections since 1919, though many rural indigenous voters weren’t able to vote until the 1979 constitution extended voting rights to illiterate people.

Peasant rebellions demanding greater rights to land date back to at least 1780, when Túpac Amaru led the largest such uprising against the Spanish in colonial times. Uprisings in the 1960s led by leaders like labor organizer Hugo Blanco were followed in the 1970s by the left-wing dictatorship of Juan Velasco Alvarado, who redistributed land ownership.

After democracy’s return in 1980, rural poverty and a weak state presence provided a foothold in the Andes for the communist terrorist group, the Shining Path. The country is still grappling with the scars of that period. A stigma equating leftist politics with terrorism, known as terruqueo, is common, and in recent weeks Castillo and his party, which espouses to be Marxist-Leninist, have often been conflated with the Shining Path.

Castillo has denied having ties to terrorism or the Shining Path, but his critics have alleged connections between members of the teacher’s union faction that Castillo leads with the Shining Path’s political arm. Castillo “needs to answer for” for these allegations, Ragas said, but they also “hide the real problems” of the country.

“For him it’s easier to fight these claims that he is a terrorist, which are easier to dismiss than to explain his program for the next five years,” Ragas told AQ.

Comparisons with the Shining Path are overly simplistic, and ignore that “in places where terrorism caused the most bloodshed, Castillo won by a lot,” Banda told AQ.

“This terruqueo, where you call anyone who is on the left a terrorist, really does not apply in the Chota area where Castillo is from,” said Orin Starn, a Duke University anthropologist. In Chota, Starn studied the rondas campesinas, traditional peasant-led patrol squads in Peru’s highlands that defended communities from the Shining Path.

Castillo has long been involved in the rondas, which the journalist Mitra Taj described as a “de facto judicial system in places where public institutions are weak.”

“The image of him as a rondero is helpful in a country that’s been beset by corruption,” said Starn. “The idea of an upstanding Andean villager who is going to be honest and bring justice is really appealing.”

Lima’s disconnect with the world of Castillo was clear in how it underestimated his campaign, which relied more on local teachers’ networks than a well-organized campaign apparatus. For example, “neither Castillo nor Perú Libre has a concerted social media strategy,” Peruvian journalist Jimena Ledgard wrote after Castillo’s first round win.

“We thought that social organizations didn’t have the power to mobilize,” said Ragas. “We thought that they had disappeared after the 1990s and the neoliberal reforms and neoliberal governments.”

Castillo also won a majority of the vote in 10 of the 11 provinces that are home to Peru’s largest mining projects, which have helped drive Peru’s economic growth but whose impact – on local economies and on the environment – has been debated and protested. Castillo has made conflicting promises about nationalizing mines if he were elected.

“The regions that provide those minerals that make Peru rich do not improve the living standards of the local communities,” said Hugo Ñopo, an economist and researcher at GRADE, a research institute in Lima.

“The Andean regions feel that they are left behind,” Ñopo said. “Many people perceive that the winners of these three decades are not them, but are the people in Lima and the big cities.”

—

An earlier version of this article misstated Arequipa as one of the regions where Castillo received over 50% of the vote.