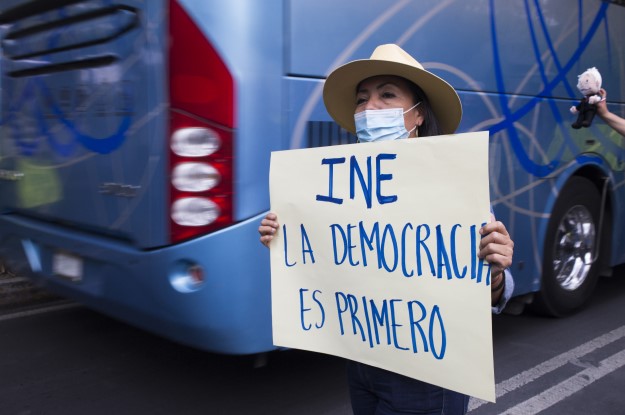

MEXICO CITY — Mexico is months away from the largest elections in its history, and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has already begun throwing public jabs. Alarmingly, many of his critiques have been directed not at opposition parties, but at the National Electoral Institute (INE).

“I have no confidence” in the INE, López Obrador, known popularly as AMLO, said on April 13. A day before, the president said the electoral body was “at the service of antidemocracy” and on the same day, he did not offer immediate condemnation when his ally and former gubernatorial candidate Félix Salgado Macedonio threatened the INE’s president at a protest against the institute.

Such antagonism toward Mexico’s central electoral authority comes at a time when tensions and stakes are especially high. A midterm election in June will see some 93.5 million voters fill over 21,000 government posts, a historic number that includes all 500 seats in the lower house of Congress. There are fears the president’s recent attacks could dampen faith in the election and in an electoral institution that has been foundational to Mexico’s democracy.

AMLO’s recent ire toward the INE stems from two resolutions that the president has interpreted as deliberate attempts by the institute to weaken his party MORENA’s hold on power. The first enforced a constitutional limit on a party’s representation in Congress, which had been often flouted using loopholes. The second resolution, however, has proven especially problematic for the president. The INE canceled the registration of 49 candidates, including 43 MORENA candidates, for failure to submit mandated pre-campaign financial reports. By doing this, the INE effectively quashed the candidacies of two important gubernatorial candidates in the states of Michoacán and Guerrero. The latter candidate, the aforementioned Salgado Macedonio, had made headlines for accusations of sexual assault, though he had until now managed to keep his candidacy alive. AMLO has lambasted the resolution, even though Mexican electoral law states that failure to submit financial reports will lead to the cancellation of the corresponding candidacy. INE’s council ratified their ruling on the candidates’ registration on April 13.

With roots in Mexico’s transition to democratic elections, the INE has for decades helped fortify Mexican democracy. The body’s predecessor, the Federal Electoral Institute, was created in 1990 after opposition parties protested fraud in elections two years prior, ultimately challenging the passive consensus around the then-hegemonic Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Opposition parties were able to pressure the ruling party to sign a series of political agreements that would establish an independent electoral body, an essential element in guaranteeing free, fair and competitive elections.

The result? Since the PRI lost its majority in Congress for the first time in 1997, federal, local and municipal elections have led to consistent transitions in power. According to a recent survey on civic culture, the INE rates as the most trusted Mexican institution apart from the military.

Unfortunately, today the INE is confronted with a president and party set on maintaining their majority even if it risks weakening electoral institutions. Since winning 53% of the votes in the 2018 presidential election and a 61% majority in the lower house for his coalition, AMLO has concentrated power in the executive, strengthening his control over public energy agencies, restricting market competition in strategic sectors and shrinking bureaucratic agencies. AMLO’s “austerity” measures serve to shore up resources for popular social and poverty alleviation programs as well as visible infrastructure projects like the Mayan train line, the Santa Lucía airport and the new oil refinery in Tabasco, the president’s home state. Civil society organizations, academic institutions and independent newspapers, meanwhile, have seen public funding reduced across the board as the president paints them as opposition groups.

AMLO’s political project is far from complete, however, and should MORENA lose its majority in Congress, the president will find the second half of his term much more difficult. Indeed, MORENA’s very future as a cohesive political organization may be at risk. The group’s diverse factions and the contrasting political backgrounds are held together by AMLO’s personal leadership and grip on power. A compromised majority could result in internal fragmentation, undermining its position ahead of the 2024 elections.

With this risk on the horizon, AMLO has locked his sights on the INE as a check on his power. The INE’s recent resolutions show that its electoral counselors have chosen to defend the institution’s independence even if it means appearing to stand in opposition to AMLO’s project. In doing so, they have received broad support from civil society.

The ongoing conflict, however, may stoke fear or indifference among voters, negatively impacting voter turnout in an outcome that would ultimately benefit the majority party and the use of clientelist political mobilization. If allowed to heat up in the coming months, the public spat could undermine trust in the electoral system. As campaign season begins, both AMLO and the INE should take this moment to step back, allowing candidates and parties to present their proposals and engage in debate with the public. The future of Mexican democracy stands to benefit.

—

Peschard is a Mexican sociologist and professor at UNAM, where she specializes in political and electoral systems. She is a former counselor to the National Electoral Institute.