In a massive decentralization experiment in the 1990s, governments in Central America established thousands of rural community-managed schools (CMS) in which communities elected parent councils to hire, fire and monitor primary school teachers as well as purchase school materials. Reforms implemented by the governments of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala not only promised increased accountability and transparency—but also more students in educational systems that until then had largely failed rural communities.

The conclusion: while the CMS model achieved some major successes, it also raised larger questions about teachers’ labor rights and states’ ability to promote genuine civic involvement in remote rural areas.

CMS helped radically expand education to rural children, many of whom until then had no nearby school to attend. In Honduras, where 25 percent of rural school-age children lacked primary education access during the late 1990s, the CMS program (Programa Hondureño de Educación Comunitaria, PROHECO) created more than 3,000 new schools, accounting for roughly 8 percent of total primary school enrollment by the mid-2000s. Guatemala’s CMS program (Programa Nacional de Autogestión para el Desarrollo Educativo, PRONADE) expanded coverage even more. Forty percent of Guatemalan children did not attend primary school in the late 1990s. By the mid-2000s, PRONADE created more than 6,000 schools, which covered 20 percent of total primary school enrollment.

Both programs relied heavily on World Bank funding, especially for the bulk of costs for program design and the initial CMS expansion. CMS fit the Bank’s agenda of decentralizing services to create accountability among governments, service providers and poor communities. In fact, in 2006, the Bank devoted almost 20 percent of its education funds to these and other similar programs worldwide.

Studies of CMS in the two countries suggest that they provide roughly equal—albeit low—quality education as traditional rural schools. CMS advocates argue that, because these schools cost less than traditional schools and target poorer communities, the model provides education more efficiently than the traditional system.

But no assessment has conclusively demonstrated the cost savings, and CMS fueled criticism due to teachers’ job insecurity and lower remuneration. “The price [of the model] included the violation of labor rights,” affirms Nery Barrientos, a leader of CMS teachers who organized (separately from the teachers’ unions) to gain the same status as traditional schoolteachers. Among the principal complaints: parent power over teacher selection and annual contract renewals undercut job stability and subjected teachers to the whims of fickle parents. Moreover, in Guatemala, reports emerged that many teachers had to pay parent councils to hire them. Even where foul play did not occur, critics questioned whether parents, who usually had little or no formal schooling, should be overseeing teacher performance.

In Guatemala, the experiment came to an end in early 2010 when President Álvaro Colom’s government finished transferring CMS teachers to the ranks of traditional system teachers. PRONADE’s reversal followed a similar experiment’s end in Nicaragua and preceded El Salvador’s announcement that it is considering overturning its CMS schools (the first in the region) to the traditional system. In Honduras, CMS has survived but in emasculated form. Patronage politics have captured the program, with party loyalties—rather than merit or parent choice—dictating teacher and field staff selection. This has continued under President Porfirio Lobo, whose Partido Nacional has already begun to systematically replace PROHECO staff with party loyalists.

CMS has both prompted political backlash—mostly from teachers’ unions—and reflected each country’s broader political legacies (e.g., patronage in Honduras). Its success in expanding education coverage and keeping teachers in the classroom has also brought into sharp relief the continued failure of traditional school systems to serve rural communities.

Job Security vs. Accountability

While Guatemala’s abandonment of CMS marked a victory for teachers worried about labor rights, it also undermined efforts to increase accountability in the education system and civic engagement in remote communities.

Extending lifetime tenure to former CMS teachers has focused attention on the shortcomings of the traditional system, where supervision remains minimal and teachers rarely receive sanctions for absences or abuses. The prospect of lifetime tenure troubles many parents in rural regions, where teachers in the traditional system have a reputation for missing work or arbitrarily shortening school days. Further raising parents’ ire in recent years, teachers’ union strikes over back pay and raises have consistently shut down schools for weeks or months at a time.

Here, CMS had the advantage. Studies show evidence of higher teacher attendance in these schools. Since teachers did not enjoy union protection and parents monitored them and paid their salaries, teachers showed up more often and worked full school days. In the words of Eduardo, a parent leader: “PRONADE worked every day, Monday to Friday. They complied with the schedule.” Since the phase-out of PRONADE, Eduardo and his neighbors have seen teacher attendance decline. Meanwhile, such problems have apparently not affected Honduras’s PROHECO schools, which have not faced the prospect of conversion.

The decline of parental participation has been the other major downside of overturning CMS in Guatemala and weakening CMS through patronage in Honduras. CMS proponents in both countries contend that these programs would, as a secondary effect, strengthen rural civil society. Arabella Castro, the minister of education under former-President Arzú, argued:

“The second reason we became excited to define PRONADE was that … we wanted [people] to have a voice, even if it was just in the education of their children … [PRONADE] was also an education for the country. It was a way to make people exercise their rights and exercise their obligations.”

In Honduras, CMS supporters also claimed that the program would strengthen civic participation and social capital. Proponents in both countries tapped into the discourse of participatory development, arguing that citizen participation in meeting development objectives would also strengthen democracy.

Of course, many hurdles confront efforts to stimulate civil society in remote communities. These include: lack of education, which limits parents’ skills and confidence to participate; material poverty, which constrains parents’ ability to contribute time and money to council efforts; geographic marginality, which makes communication and transportation for meetings or visits to government very difficult; and pervasive gender inequalities, which limits female involvement.

Yet survey evidence from over 2,000 parent council members in communities throughout Honduras and Alta Verapaz (the Guatemalan department with the highest presence of CMS), shows that these programs raised the level of civic engagement outside the school arena among a minority of parents. These “spillover” effects include learning transferable skills, gaining experience in making demands on government and increasing participation in other community organizations.

Spillover Effects

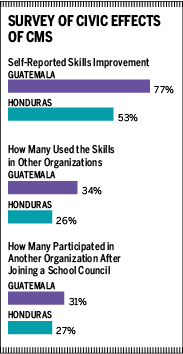

Among parent council members, a majority reported learning new skills, such as how to run a meeting or how to make a budget, after joining the council. Furthermore, over one-third of respondents in Alta Verapaz and one-fourth of respondents in Honduras reported applying those skills in other organizations [SEE TABLE]. Roughly 30 percent of each sample also reported increased participation in other organizations, suggesting a “thickening” effect on rural civil society—i.e., more participants in each community and possibly more organizations.

Among parent council members, a majority reported learning new skills, such as how to run a meeting or how to make a budget, after joining the council. Furthermore, over one-third of respondents in Alta Verapaz and one-fourth of respondents in Honduras reported applying those skills in other organizations [SEE TABLE]. Roughly 30 percent of each sample also reported increased participation in other organizations, suggesting a “thickening” effect on rural civil society—i.e., more participants in each community and possibly more organizations.

Case studies in both countries—conducted over 10 months between 2007 and 2010—confirmed that CMS participation gave certain parents valuable experience in running an organization and making demands on the state. Valerio, a former Honduran school council president, explained: “I learned to manage checks, to sign [checks and forms] better at the bank, to manage the funds for supplies, and to know how to take care of the school.” Rolando, a Guatemalan parent leader, recounted how participating in the council “took from me the shame I had of talking in front of everyone.”

Parent leaders have also used new skills to motivate others to participate. Jorge, another Guatemalan parent leader, described learning “how to organize the community, how to inculcate them to be participants in the community.” Some leaders also increased their capacity to advocate for community needs to state authorities. Edwin, a former Honduran school council president, asserted: “Everything starts with the school.” His uncle, Abelardo, also a former president, explained, “For a long time, [all the proposals from this community] began as AECO [school council] proposals…The AECO would manage whatever project came to the community.”

State support—especially training and field staff visits to support parent councils—proved critical to generate spillover effects. The higher frequency and quality of training in Guatemala provides the most plausible explanation for why more Guatemalan parents reported learning than their Honduran counterparts. Interviews in both countries confirmed that parents who received training were more likely to gain transferable skills, confidence and experience. Francisco, a former Honduran school council vice-president, recalled, “Our capacity increased because the trainings helped us a lot. [Before] I didn’t know how to organize a meeting.”

But how do these impacts affect the organizational life of rural communities?

At the community level, CMS did not substantially alter the landscape of participation. While parent councils often provided parents in remote communities with their first opportunity to participate in a formal organization and led many to join other groups, most of the fruits of participation were enjoyed by people with prior organizational experience.

Within communities, pre-existing leaders usually remained in charge of school councils and other organizations. This is especially true when, as in Honduras, training for new members was minimal. In many cases, CMS appears to have strengthened existing leaders rather than created new ones.

The nature of the organizations that parents later joined is also revealing. Like the school council, most other organizations (e.g., water committee, security committee) were formed because the state required the community to form a committee to obtain certain benefits. In some cases, organizations obtained legal standing to act autonomously of other organizations (e.g., to sign contracts), but they remained de facto community sub-units of state entities.

This raises the question of whether these are really civil society organizations at all.

Political scientists have long held that the state can help foster civil society, especially in resource-scarce areas, but it is another thing altogether for state-sponsored organizations to be the only game in town. Definitions of civil society typically include a provision that organizations remain at least “relatively autonomous” from the state. In CMS communities in Honduras and Guatemala, however, most organizations do not meet the “relative autonomy” condition.

When state-created organizations gain insider access for their demands, their relationship to the state makes it difficult for them to hold governments accountable. Strengthening democracy from below requires grassroots efforts to ensure public accountability. Increased demands on government without public accountability can also reinforce clientelism. If community organizations do not work together to change how government distributes resources, state institutions will continue to allocate funds along nontransparent and/or partisan lines, while public goods provision remains perilously low.

As a result of CMS, communities may have become more fragmented. Many communities separated from their former villages to obtain CMS schools, either because the government would not give two schools to one—albeit dispersed—rural community or because residents of the initial village did not prioritize a school. This separation likely undermined the capacity of communities to act collectively.

With limited autonomy, a restricted scope of action and strong odds against collective action, parents in these remote, rural communities sit on the sidelines of national, and even local, debates about the policies that affect them. They mostly remain on society’s margins with their hands outstretched for whatever small items (e.g., zinc for their roofs) politicians may bring them.

No Magic Bullets

CMS, then, is not a magic bullet for strengthening civil society.

All the same, these programs offered parents training in how to participate in organizations and, to a lesser extent, how to seek help for their communities. That has vanished with CMS’ demise in Guatemala. PRONADE provided training and technical support to parents several times each year. President Colom’s first minister of education, Ana de Molina, replaced it with a program called Mi Familia Aprende (My Family Learns) that provided training on values, nutrition and community participation. But, in late 2009, the minister resigned, and her successor discontinued the program. Parents in rural Guatemala currently receive no training and virtually no school supervision.

This year, schools opened one month late due to national strikes. In the past, PRONADE schools would have opened on time. The Guatemalan teachers’ union has welcomed ex-PRONADE teachers, and many of them joined national strikes over the education budget and back pay. Meanwhile, parents are worried about their loss of control. One former council member, Ventura, lamented: “Today, the teachers didn’t come, and we don’t know why.”

So far, no study has explored the impacts of PRONADE’s reversal on children’s education. But, with low supervision of teachers and weak sanctioning mechanisms, teacher attendance in ex-PRONADE communities appears to have declined. Roberto, a former parent leader, explained: “We don’t have much participation in the school any more because the teacher decides on his own what to do.” Without training and stripped of their monitoring role, parents feel less equipped to improve their children’s education and effect change in their communities.

In Honduras, patronage politics has similarly undercut parents’ roles in CMS, undermining accountability and potential spillovers from parental participation. In a country plagued by the two dominant parties’ clientelistic behavior, PROHECO has become a convenient way for the ruling party to reward its activists with field staff and teaching jobs. As Marlon Brevé, former secretary of education, acknowledged, “The promotores [field staff] are activists. And there’s no need to deny it—in both governments, from one party to another, they will be activists. They are someone who has worked on the campaign of a diputado or the president and is looking for a job.”

PROHECO’s personnel records reveal that only one of 190 promotores in 2009 held his job in 2006, when the previous government was in power. Staff turnover rates with the new Partido Nacional government appear similar. Pressured by ruling party patrons, promotores often ensure that parents sign teaching contracts for party loyalists. And, as PROHECO employees have taken away parents’ ability to select teachers, so too have many of these state employees become content for parents to just sign on the dotted line, undermining the “client power” that the CMS model promised.

For critics of CMS, including teachers’ unions, reducing the administrative responsibilities for poor parents signals progress. Time spent by parents at the school means workdays lost in the fields, and parents need to feed their families. Guatemalan parent leaders often spent more than 10 workdays per year dealing with school issues, and critics view CMS programs as an implicit regressive tax, under which the state makes rural parents forego income to obtain schools for their children.

But in many Guatemalan communities the prevailing sentiment among parents is resentment over what they perceive as abandonment by the state. As Jorge, a former council president, explained: “It’s true that it was hard, but we also learned. Now, we’re resting more, but things have gone a bit downhill.” The time required to participate in the school council exhausted some parents, but many more expressed their current frustration.

Parental disillusionment also exists in Honduras. In schools where patronage politics have stripped parents of the ability to choose teachers, parent councils have become mere administrative shells, assuming limited administrative responsibilities without compensation. Here, critics are right to suggest that parental participation has simply become a guise for the state to off-load responsibilities for administering social services to the poor. When the state gives parents substantive decision-making power and supports increasing parents’ skills and engagement in community affairs, it offsets this critique. In present-day Guatemala and Honduras, however, this bar is not being met.

Partial Success

These cases of CMS show that while participatory development programs can stimulate parents’ individual engagement in community life, they fall short of transforming how rural citizens organize and engage with the state. The absence of significant community-level impact suggests that states must do more than just pay lip service to increasing citizen participation; material support, especially for training, and allowing greater organizational autonomy remain critical.

Over the past several years, the Honduran government has pledged “citizen power” and the Guatemalans promised to “govern with the people.” Their treatment of CMS, however, suggests critical shortcomings in support for rural civic engagement. Instead, leaders in both countries have sacrificed support for parental participation to powerful interests (the teachers’ union in Guatemala and patronage networks in Honduras) that promise electoral gain.

The CMS model has always been problematic because of the lack of labor rights for teachers. But the removal or weakening of parental participation, in the absence of other accountability mechanisms, has brought new problems. It threatens to undo the only system that has formally introduced teacher accountability to rural communities, while also removing one of the few—albeit imperfect—forums for civic learning that these young democracies had managed to create in the countryside.