Social inclusion is a buzzword for politicians these days. Whether deployed as part of a campaign platform (as Ollanta Humala did in Peru last year) or used as a catch phrase to describe the root of malaise (as Barack Obama has done in the United States), the idea of promoting inclusion of disenfranchised groups has entered the public discourse, and, in many cases, become a goal in itself.

Yet social inclusion, defined as equality of opportunity for all groups (across socioeconomic, racial, gender, and sexual orientation lines) to participate in the economy and society, requires political inclusion to be comprehensive and sustainable. For example, the civil rights of racial, ethnic and sexual minorities cannot be viewed as secure if they have no representation in formal political processes. Neither can rights be enforced without legal mechanisms.

Similarly, groups at a chronic economic disadvantage are unlikely to overcome inequality without public policies that target the causes of that inequality, such as lack of access to education, health care, affordable housing, and labor markets.

In Latin America, conquest, slavery, economic feudalism, and racism have left a post-independence legacy of systematic exclusion of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples. Even today, despite recent improvements in tackling inequality, poverty lines still fall along racial and ethnic ones, with Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations disproportionately represented among the poor.

The transitions from military rule to democracy in the late 1970s and 1980s brought in their wake race- and ethnicity-based social movements, civil society groups and even formal political parties inspired by a newfound sense of civic participation. At the same time, growing public awareness of the needs of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples was fueled by international support—most notably, by Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO) on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. Assisted by institutional and legal reforms in individual nations, Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives began to formally participate in local and national politics. Today, the region boasts numerous elected Indigenous and Afro-descendant mayors, municipal councilors, state and national legislators, governors, and even presidents in the case of Peru and Bolivia.

But are representatives elected from Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities better at representing the demands and serving the interests of those populations?

To answer these important questions, we conducted field research in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Guatemala. All four countries have sizable Indigenous and/or Afro-descendant populations; experienced a measurable increase in elected national representatives from those populations; and approved a broad set of legal or constitutional reforms intended to expand political inclusion.

We found that there is a long way to go before greater numbers of Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives in national legislatures (“descriptive representation”) translate into legislation and policy outcomes that benefit their communities (“substantive representation”). In short, low levels of meaningful political representation persist. And as long as they do, so too will social exclusion.

A RISING TIDE

Today, self-identification by Indigenous and Afro-descendants in Latin America is at an historic high. In Central America and the Andes, Indigenous peoples make up a significant share of the population: 62 percent in Bolivia and 41 percent in Guatemala (although unofficial estimates put Guatemala at about 60 percent). In Ecuador and Colombia, Indigenous peoples represent a smaller share of the population (7 and 3 percent, respectively), but both also have substantial Afro-descendent populations (7 and 11 percent, respectively).1

The willingness of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples to self-identify is relatively new. Social and political identities began to shift during the 1980s and 1990s, bringing about corresponding changes in mobilization. Among Indigenous and Afro-descendant groups, there was a newfound awareness and willingness—pride, even—to self-identify.2 And the political environment and climate of democratic rights created by the transitions to elected governments provided a sustained, fertile ground for new voices and demands.

New constitutions in Guatemala (1985), Colombia (1991) and Ecuador (1998 and 2008) incorporated some recognition of the state as a pluri-ethnic entity, as did the 1994 constitutional reform in Bolivia. In Colombia, the new constitution established reserved seats for minorities (two in the lower house for Afro-descendants and two in the upper house and one in the lower house for Indigenous representatives).

By the late 1990s, the social movements of Indigenous peoples morphed into greater political participation, either in the form of ethnically defined parties or through the incorporation of social leaders into existing parties. In most cases it was a combination of both—assisted, in part, by the weakening of traditional party systems, the constitutional reforms described above and decentralization reforms that established local elections.

The Afro-descendant movement, which we examine in Colombia and Ecuador, developed later. They had suffered from greater fragmentation, a less clearly articulated sense of collective identity and a less coherent set of demands than the Indigenous movements.

Indigenous peoples in Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, and Guatemala have been largely rural. For many of the groups that emerged in the late 1980s and 1990s, popular and political identity were closely bound to the preservation of cultural and linguistic traditions and tied to ancestral lands. In contrast, Afro-descendant communities tended to be more dispersed across rural and urban communities.

As a result, by the time constitutional reforms were implemented in a number of countries, their Indigenous peoples had already mobilized sufficiently to participate in the constituent assemblies and help shape the resulting constitutions.

Bolivia

Historically, political identity for Indigenous peoples in Bolivia was structured more around the peasant agrarian struggle than around ethnicity. The pattern of internal migration from rural areas to urban centers in the 1970s and 1980s, however, began to shift the Indigenous discourse to a greater emphasis on land rights as a means of preserving cultural heritage, and eroded the foundations of traditional political parties.

Social movements emerged during this time as a tool to mobilize disparate ethnic and labor interests and give a political voice to their demands. Out of these movements and a 1990 March for Territory and Dignity came Evo Morales, an Aymara coca grower. Morales founded the Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement for Socialism—MAS) in 1995, which has become the banner for the majority of Indigenous representation in contemporary Bolivia. Morales has served as president of Bolivia since January 2006.

MAS is legally a political party, but operationally it is a confederation of social movements, labor movements and left-leaning intellectuals. In the 2009–2014 congressional term, all 43 members of the Indigenous delegation are from MAS, with many of them appointed directly by member social movements. However, given the heterogeneity of the Indigenous population in Bolivia—there are 36 Indigenous languages spoken in a country of nearly 10 million people—it would be a mistake to ascribe to MAS the role of the sole, uncontested party of Bolivia’s Indigenous peoples.

Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution, approved 27 years after the transition to democracy, changed both the name and the composition of the legislature to reflect the country’s plural identities. The new Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional (Plurinational Legislative Assembly) encompasses a 137-seat Chamber of Deputies with seven reserved seats for race- and ethnicity-based peoples, and a 36-seat Senate with four senators from each of Bolivia’s nine departments. The seven reserved seats are apportioned to the seven departments with the highest ethnic constituencies. The nominees are appointed by traditional customs but voted on by the entire department.

In our research, we focused on the level of Indigenous representation over four congressional sessions and found that it increased in each term, with the highest point achieved in the current Plurinational Legislative Assembly. At the same time, the tendency of Indigenous representatives to collectively support legislation that affects Indigenous communities also increased, from 50 percent doing so during the 1989–1993 congressional period—on one Indigenous-related bill that was introduced by a non-Indigenous representative—to 100 percent today. This occurred as Indigenous representation and its partisan differentiation increased. Although Indigenous representatives have never formed a bancada (caucus), they have tended to vote as a bloc.

National Congress, 1989–1993

The only bill proposed by Indigenous representatives in the 1989–1993 period was related to the protection of and respect for traditional Indigenous laws. The Indigenous agenda at this time was largely focused on respect for territorial claims and preservation of Indigenous cultures. In this regard, Congress in 1992 passed the Environment Law No. 1333. Although introduced in the congress by a non-Indigenous representative, Jorge Torres Obleas, it was a product of negotiations between then-President Jaime Paz Zamora and leading Indigenous groups at the time, following the 1990 March for Territory and Dignity.

National Congress, 1993–1997

The new congress, which took office shortly after Law No. 1333 was signed, included six Indigenous legislators. During this term, seven bills affecting Indigenous communities were approved, including the Law of Popular Participation proposed by then-Vice President Victor Hugo Cárdenas, an Aymara from the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Katari de Liberación (Túpac Katari Revolutionary Liberation Movement—MRTKL) party.

Miguel Urioste, a non-Indigenous deputy, introduced a bill in 1996 that created Indigenous-specific territories: tierras comunitarias de origen (communal lands of origin). The other five bills responded to issues connected with the constitutional reform process of 1994. Although they were submitted by non-Indigenous representatives, each one had been drafted by the Centro de Estudios Jurídicos e Investigaciones Sociales (Center for Juridical Studies and Social Research—CEJIS), which acts as a pro-Indigenous think tank—and was supported by the Confederación de Pueblos Indígenas de Bolivia (Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia—CIDOB). The proposals dealt with Bolivia’s multi-ethnic character, individual equality under the law, free interpreters and legal defense for Indigenous peoples, agrarian development for occupants of rural land, and respect for Indigenous practices in their communal lands.

National Congress, 2005–2009

The greatest achievement for Indigenous communities in this period was the passage of an entirely new constitution. Four articles of the new constitution were directly tied to the advocacy of Indigenous-oriented social movements—CEJIS, CIDOB, the Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia (Unified Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia—CSUTCB), and the Consejo Nacional de Ayllus y Markas del Qullasuyu (National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu—CONAMAQ).

In our study these articles are considered as four separate legislative projects. They cover the issues of: equality for all residents of the state (i.e., all genders, all Indigenous nations and all cultures); a decentralized society with a return to Indigenous self-determination; universal education incorporating discussion of decolonization; and recognition of traditional Indigenous law relating to ancestral land.

Plurinational Legislative Assembly, 2009–2014

The current bicameral congress convened a few months after enactment of the new constitution. To date, Indigenous representatives have proposed two ethnic-oriented bills and the sole Afro-Bolivian deputy has proposed one.

Two of the three bills have been approved by both houses and signed by the president, and relate to anti-discrimination and the harmonization of the national justice system with traditional Indigenous judicial norms.

The third initiative, which failed, dealt with protecting Indigenous language rights.

One other bill addressing Indigenous demands passed during this term was introduced by the non-Indigenous Minister of Autonomies, Carlos Romero, a MAS leader, former executive director of CEJIS and a member of President Morales’ cabinet. His bill established a new level of governance by granting autonomy to traditional Indigenous communities located in the original political divisions of departments, provinces and municipalities.

Colombia

The turning point for Indigenous and Afro-Colombian representation in Colombia was the Constitution of 1991, which recognized the nation as multiethnic and multicultural.

Despite its smaller overall population, the Indigenous movement was better organized than the Afro-Colombian movement in the 1980s, when the constitution was drafted. Two Indigenous leaders were elected to the Asamblea Nacional Constituyente (National Constituent Assembly)—the body that crafted the new constitution—and pushed for the inclusion of provisions that addressed ethnic and race-based interests such as communal land rights and political participation.

In response, Article 171 of the Constitution created two reserved seats in the Senate for Indigenous representatives elected in national districts. Law 70 of 1993 created two reserved seats for Afro-Colombians in the Chamber of Deputies. Later, Law 649 of 2001 granted Indigenous representatives an additional seat in the Chamber.3

These institutional mechanisms have produced greater visibility and representation for ethnic minorities. But the ethnically defined seats proved to be a double-edged sword, especially for Afro-Colombian voters and representatives. By establishing national reserved seats, the Afro-Colombian set-asides encouraged a dangerous level of electoral competition among Afro-related movements and parties. One result was political fragmentation: Afro-Colombians’ political weight on ethnic issues is weakened by their affiliation to small Afro-Colombian parties that command few votes in the case of reserved seats or, in the case of open seats, major political parties that do not prioritize ethnic issues.

The Indigenous fared better, thanks to the support of established social and political movements, particularly under the umbrella of the Organización Nacional Indígena de Colombia (National Indigenous Organization of Colombia—ONIC). Alianza Social Indígena (Indigenous Social Alliance—ASI) serves as the unofficial political arm of ONIC and elected the majority of Indigenous representatives to reserved and open seats in 1998 and 2010. Autoridades Indígenas de Colombia (Indigenous Authorities of Colombia—AICO) also elected a critical mass of representatives.

In all, 13 Indigenous and Afro-Colombian representatives served in Colombia’s National Congress—a 102-seat Senate and a 166-seat Chamber of Deputies—between 1998 and 2010.

National Congress, 1998–2002

From 1998 to 2002, Indigenous representatives sponsored 42 bills. Twenty-four of them were to modify the constitution. Their legislative agenda was dominated by social security issues (education, health, poverty, housing, protection for senior citizens, etc.).

One law, proposed by Indigenous representative Jesús Enrique Piñacué in 1999, guarantees the inclusion of Indigenous Colombians in the government-financed health care system. The Law of Culturally Inclusive Health Care states that Indigenous communities are entitled to health care benefits corresponding to their needs and cultural background. These benefits include the basic health care plan (Plan Obligatorio de Salud), a food subsidy for pregnant women and children, and emergency relief for victims of car accidents, catastrophic events and forced displacement by armed groups.

There were no Afro-Colombian representatives in this period because the reserved seats were ruled unconstitutional in a decision by the Constitutional Court, only to be reinstated in 2001.

National Congress, 2002–2006

All four Indigenous representatives in this period were elected from minority political parties, while all of the Afro-Colombian representatives came through traditional parties. As in the previous congressional session, Indigenous-related initiatives generaly met with little success. From 2002 to 2006, Indigenous legislators sponsored 41 bills—17 coming from the Senate and 24 from the Chamber. Of the 41, 18 related directly to Indigenous issues, but none of them passed. (Four bills not related to Indigenous issues were enacted as laws.)

Ten of the 33 bills sponsored by Afro-Colombian legislators were related to their community. None was signed into law.

National Congress, 2006–2010

Seven Afro-Colombian and Indigenous representatives served in the 2006–2010 congressional session. Indigenous legislators occupied their three reserved seats in both chambers, with only Orsinia Polanco Jusayú coming from a non-Indigenous party (Polo Democrático Alternativo). The three Indigenous representatives introduced a total of 31 bills—17 in the Senate and 14 in the Chamber. None of the 12 bills relating to the Indigenous population was signed into law.

Unlike the previous session, both Afro-Colombian representatives who occupied reserved seats in the Chamber—María Isabel Urrutia Ocoró (Alianza Social Afrocolombiana) and Silfredo Morales Altamar (Afrounninca)—were elected through Afro-Colombian political parties. Between 2006 and 2010, Afro-Colombian representatives authored 39 bills (33 from the Chamber). Fifteen bills related directly to Afro-Colombian issues and demands, though only two were approved. The first, sponsored by Urrutia, sought to allocate more federal resources to the Universidad de la Amazonía to provide financial aid to low-income students, especially internally displaced peoples and Afro-Colombian and Indigenous students.

The other bill was authored by Hemel Hurtado Angulo and recognizes “Petrónio Álvarez” Pacific Music Festival—a celebration of the traditions of Colombia’s largely Afro-descendant Pacific Coast—as a national cultural heritage.

Ecuador

Ecuador has had a unicameral legislature since 1979. Under its 2008 constitution, the legislature is called the National Assembly and has 124 members, with no reserved seats for Indigenous or Afro-descendants. During the 1996–1998 Congress and 1997–1998 Constituent Assembly, the state was asked to recognize plurinationality, as well as Indigenous justice and collective rights for the first time in Ecuador’s history.

The 2008 Constituent Assembly marked the first time Afro-Ecuadorians were visibly present in the political process. Seven elected representatives were in the Assembly, supported by more than 500 observers who attended the plenary debates and votes. We also look at the current legislative session, 2009–2013, as it is under the 2008 Constitution.

In the 1990s, Indigenous interests were largely represented by the Confederacion de las Nacionalidades Indigenas del Ecuador (Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador—CONAIE) and its political arm, the Pachakutik party. By the time of the 2008 Constituent Assembly and elections to the 2009–2013 term, representation of the Indigenous movement had dispersed among the Alianza Pais coalition, Amauta Yuyay, an evangelical Indigenous party, and others, in addition to Pachakutik.

In contrast to its Indigenous counterpart, the Afro-Ecuadorian movement has never been able to coalesce around a single political party. Its representatives in the 2008 Assembly and current legislative session came from Alianza País, Partido Sociedad Patriótica, Movimiento Popular Democrático, Partido Roldocista, and others.

National Congress, 1996–1998

In the 1996–1998 legislative period, only one bill relating to Indigenous communities was introduced. But the proposal—to create an Intercultural University of the Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador—failed to pass after the first debate. No Afro-Ecuadorian legislators participated in the 1997–1998 session of Congress.

Constituent Assembly, 1998

In drawing up the 1998 constitution, three bills relating to collective rights, plurinationality and land and territory issues were introduced by Indigenous representatives. Only the bill proposing the incorporation of the collective rights of Indigenous peoples, in accordance with Convention 169 of the ILO, was approved—though implementation proved elusive. Meanwhile, the only proposal specifically affecting the Afro-Ecuadorian community was made by an Indigenous representative, Nina Pacari Vega (Pachakutik), to recognize the “pueblo negro” as a distinct part of Ecuadorian society. Afro-Ecuadorian groups lobbied in favor of this recognition. It passed.

Constituent Assembly, 2008

In contrast to its strong presence during the drafting of the 1998 Constitution, CONAIE found itself in a moment of instability and internal conflict during the 2007–2008 Constituent Assembly.4 The relationship between CONAIE and other umbrella and grassroots Indigenous organizations was characterized by rupture and a lack of cooperation. Despite this, CONAIE introduced and secured approval of six articles in the new constitution: recognition of the plurinational character of the Ecuadorian state; interculturalism; land and territory of Indigenous peoples; the proclamation of Kichwa as an official language of Ecuador (as an official language of intercultural relations); Indigenous justice; and environmental rights.

Afro-Ecuadorians’ level of representation during the 2007–2008 Constituent Assembly was the highest in history. Nonetheless, they were only able to secure passage of one proposal—recognition of eligibility for collective rights, along with the Indigenous and Montubios (a coastal people of mixed descent). The same constitutional article criminalized racially motivated acts of violence—a notable victory for the Afro-Ecuadorian community, if only a symbolic one. It wasn’t until a reform to the code on penal procedures was approved—in March 2009—that the guarantee gained any practical implications or mechanisms for enforcement.

National Assembly, 2009–2013

In the 2009-2013 session of the National Assembly, Indigenous representatives have so far introduced seven legislative proposals, most of them having to do with formalizing cultural autonomy. One bill also proposes institutionalizing Indigenous judicial systems for coordination and cooperation with the established justice system. But despite the constitutional endorsement of the topic, and their numbers in the National Assembly, only one bill—to recognize “food sovereignty”—has passed (barely). The remainder have been “distributed”—accepted for debate and introduced to all representatives, but have yet to be debated.

The only bill currently under consideration that would benefit the Afro-Ecuadorian community is one proposed by the Corporación de Desarrollo Afroecuatoriano (Corporation for Afro-Ecuadorrian Development—CODAE), the body within the executive branch charged with promoting the development of the Afro-Ecuadorian peoples. The proposal, the Ley Orgánica de Derechos Colectivos del Pueblo Afroecuatoriano, defines the collective rights of Afro-Ecuadorians under the most recent constitution, and specifies mechanisms to enforce them.

Two legislative bills affecting Indigenous rights have been introduced by Rafael Correa’s government: a bill on water and a bill on mining. Although both adhere in principle to the constitutional norm of respect for environmental rights and prior consultation (consulta previa), they currently represent a challenge to Indigenous land rights. The bill on mining, for example, mentions the necessity for prior consultation of the Indigenous peoples but does not consider such consultation to be binding.5 The National Assembly ultimately approved the bill on mining, despite the opposition of Indigenous groups. But it shelved the bill on water pending consultation with Indigenous communities.

Guatemala

Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war had a dramatic effect on the country’s Indigenous population. The negotiation of the peace process in the early 1990s created an opportunity for Indigenous organizations to help shape post-war Guatemala. The Acuerdo de Identidad y Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas (Agreement on the Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples)—part of the Peace Accords signed by the government, Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity), guerrillas, and the UN in 1996—recognized Guatemala for the first time as a multiethnic, multilingual and multicultural nation. The following year, the Guatemalan government signed ILO Convention 169.6

Many of these legislative victories came about because of pressure from the Coordinadora de Organizaciones del Pueblo Maya de Guatemala (Coalition of Mayan People’s Organizations—COPMAGUA), an alliance of more than 200 Indigenous organizations and the first national Indigenous movement. COPMAGUA fought for: constitutional recognition of the Mayan people; legal recognition of Mayan forms of organization, political practices and customary law; participation in state institutions; and recognition of territorial autonomy on the basis of history and language.7

Responding to international pressure, the government of President Álvaro Arzú (1996–2000) carried out a popular referendum in 1999 to decide on 47 constitutional reforms agreed upon in the Peace Accords. During this process, Indigenous leaders formed the Comisión Indígena para Reformas Constitucionales (Indigenous Commission for Constitutional Reforms), which proposed 157 distinct reforms, most of them guaranteeing equal rights for Indigenous populations.

The resulting referendum was a centerpiece of the Indigenous movement, but the rejection of the reforms robbed it of much of its momentum. COPMAGUA disintegrated in 2000, and the massive political movements of the previous decade gave way to individual participation of Indigenous groups via party politics. Guatemala does not have formal laws or policies—in the constitution or elsewhere—to promote political representation of Indigenous peoples.

Since the transition to democracy in 1985, Indigenous populations have participated in great numbers as voters, but in low percentages as representatives in Guatemala’s unicameral National Assembly.

National Assembly, 1986–1991

The first general election under the new constitution was in 1985. Of the 100 representatives elected to the National Assembly, eight were Indigenous (all of them Maya). Seven were part of the Democrácia Cristiana Guatemalteca (Guatemalan Christian Democracy) party, while only Waldemar Caal Rossi was elected through the Unión del Centro Nacional (National Union of the Center) party. Ana María Xuyá Cuxil, elected from the electoral district of Chimaltenango, was the first Indigenous woman to hold the title of deputy. During this period, no laws affecting the Indigenous community were authored by the eight Indigenous representatives.

National Assembly, 2000–2004

The general election of 1999 was the first after the 1996 Peace Accords. Thirteen of the 113 congressional seats went to Indigenous representatives (11.5 percent). During this period, the one bill coauthored by Indigenous representatives that related to Indigenous peoples was the Ley de Idiomas (Law of Languages) of 2003. The law mandates that all Maya, Garifuna and Xinca languages can be used without restriction in both public and private spheres. Health, education, legal, and security services, as well as all laws and other government documents, must be available in the appropriate 24 recognized languages. It is the responsibility of the executive branch to budget for these regulations. The law also requires that the government identify any languages in danger of extinction and take steps to protect and develop them.

National Assembly, 2008–2012

In the 2007 election, 22 of 158 congressional seats went to Indigenous representatives. The principle legislative victory for Indigenous representatives was the 2003 Ley de Generalización de Educación Bilingüe Multicultural e Intercultural (Law of Generalization of Bilingual, Multicultural and Intercultural Education). In recognition of Guatemala’s diverse population, the law requires all primary and secondary schools to incorporate a multicultural curriculum and to offer classes in more than one language. The law also mandates that public- and private-sector institutions make a commitment to multiculturalism so their services are more accessible.

THERE, BUT NOT REALLY THERE

In the cases studied above, the concrete legislative output by Indigenous and Afro-descendant legislators has not been insignificant, but it hasn’t been dramatic. This is manifest in a number of ways. First, while there has been a trend toward increased representation of Indigenous and Afro-descendants in national legislatures, it still has not reached proportions that reflect their population in society. This, by itself, is not surprising; in the U.S., for example, women and African-Americans’ representation still lags far behind demographics.

Yet, in countries in Latin America where Indigenous peoples represent close to, or more than, the majority (i.e., Bolivia and Guatemala), the gap between demography and formal representation is stark—particularly after decades of elections and institutional reforms often intended to increase their participation. Even in Bolivia, only 25 percent of the legislators in the lower house are Indigenous in custom, language and self-identification, compared to 62 percent of the general population.

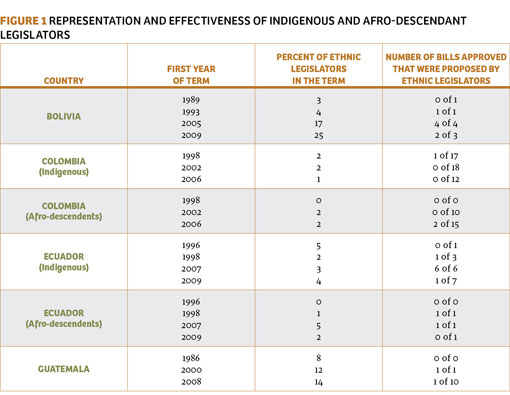

Second, even the small increase in Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations in our case-study countries has not resulted in a dramatic increase in legislation or constitutional norms in their favor. During the 12 congressional periods and two constituent assemblies in the four countries studied, only 22 of the 103 bills sponsored by Indigenous or Afro-descendant legislators dealing with issues related to their communities have been approved into law. [See Figure 1]

These low levels do not necessarily stem from open opposition to Indigenous and Afro-descendant initiatives, but are in part related to the low number of bills presented by the Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives themselves. Except in the case of Colombia, Indigenous and Afro-descendant legislators or constituent assembly members never generated a flurry of race- or ethnicity-based initiatives. In Colombia, where they were notably more active, the failure rate of their legislative initiatives was spectacular (97 percent for Indigenous and 92 percent for Afro-descendants).

Third, the 15 laws or constitutional norms approved in the case-study countries are all remarkably similar. All four cases have a law or constitutional norm related to consulta previa, or prior consultation on matters of natural resource extraction on Indigenous lands (Bolivia, 2009; Colombia, 1991 and 2009; Ecuador, 2008; and Guatemala, 1997). While the scope and authority vary (as do mechanisms for implementation), in each case the laws reflect a longstanding effort to achieve territorial integrity by Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities—in effect, a demand for respect of what they consider their cultural heritage: their land.

In addition, two of the countries studied approved antidiscrimination laws (Bolivia, 2010, and Colombia, 2011); two approved constitutions that describe the state’s plurinational character (Bolivia, 2009, and Ecuador, 2008); and two approved laws related to respect for Indigenous languages (Colombia, 2010, and Guatemala, 2003). Finally, Ecuador established a provision in the 2008 Constitution to recognize and integrate Indigenous justice into the national system, though legislation to formally facilitate the bill is currently stalled in the National Assembly. In contrast, the Bolivian Plurinational Legislative Assembly passed such enabling legislation in 2010.

Fourth, what is striking about the laws approved is their narrowness. In contrast to women’s or African-American issues examined in other studies on substantive representation, which tended to measure impact of these representatives by their effectiveness on issues of social spending or—in the case of women—women’s health care or maternity leave policies, there was a notable lack of laws and constitutional initiatives related to social policy in these country cases.8

Instead, the majority of the laws and initiatives identified in this study focused largely on issues of recognition (territorial and linguistic), education and antidiscrimination. Only in Colombia did Indigenous and Afro-Colombian legislators press for a specific change in state policy to permit greater access to health care and pension benefits for Indigenous peoples (Law of Culturally Inclusive Health Care, 2001).

The absence of a social policy agenda for Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives deserves further exploration. In part, it may reflect a subtle form of self-checking, recognition of the likely opposition of non-Indigenous or Afro-descendant representatives and policymakers—though this is less likely the case in Bolivia. Arguably, the limited, singular nature of the agenda may also limit the capacity of Indigenous parties such as Pachakutik in Ecuador to establish a broad working agenda with other parties, relegating them to a spoiler role.

Another possible explanation for the narrow agenda of these groups—not mutually exclusive from self-checking—is that it reflects the evolution of these peoples and their political movements. Long repressed, many have focused on claims rooted in their history and culture: land, rights, recognition, and respect for internal processes, including justice. It does though raise the question, given the sad overlay of poverty and lack of social development of many of these communities, as to how and when these gains will translate into concrete social policy demands (education, health care, pensions) targeting their communities.

Such focused social policy efforts are essential to overcoming the centuries of economic and social exclusion—but largely appear to be lacking.

Finally, since our cases compare constituent assemblies in Ecuador (1998 and 2007–2008) to congressional periods, one difference between them stands out. Both in terms of representation and effectiveness, Ecuadorian (Afro-descendant and Indigenous) representatives had a better success rate in translating their demands into constitutional guarantees. This may, again, reflect the normative and symbolic nature of their agenda until now, which more easily translated into constitutional provisions and norms than into legislative changes. But it may also reflect the challenges of legislating for these communities.

IMPROVING LEGISLATIVE SUCCESS

Perhaps more than any other political sector, the substantive representation of Indigenous and Afro-descendant groups is strongly linked to international support and the social and institutional environment in each country.

In all four cases studied, we discovered that, as social and political identities and movements formed, international actors, civil society, electoral laws (including, but not limited to, reserved seats) and executive–legislative relations shaped and often determined the ability of Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives to affect their legislative agendas.

International Actors

The ILO’s Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, ratified by 20 countries to date, has been the single most influential treaty with regard to lending legitimacy to Indigenous and Afro-descendent movements within individual countries. It has helped define their specific demands concerning the recognition of cultural and land rights. In particular, the convention’s articles regarding consultation of Indigenous peoples, which say that “governments shall consult the peoples concerned[…]whenever consideration is being given to legislative or administrative measures which may affect them directly” (including, later, “programmes for the exploration or exploitation of [natural] resources pertaining to their lands”), laid out a framework for governments to abide by when dealing with extractive issues, although many have complied with only token measures rather than with the full spirit of the convention.

Social Movements

In every country studied, Indigenous and Afro-descendant social movements cast a long shadow over political representatives from those communities, and have been critical, if not in the initiation of legislation, then in its success in becoming law, through outside pressure, mobilization and broad political advocacy. In Bolivia and Ecuador, these movements have been represented by solitary, dominant organizations—MAS in the former, CONAIE in the latter.

In Bolivia, despite recent signs of splits within MAS over President Morales’ policies in the Territorio Indígena y Parque Nacional Isiboro-Secure (TIPNIS), MAS remains the primary vehicle for Indigenous political participation. And in matters of successful Indigenous-related legislation, until now supported by social movements, the Indigenous representatives in all four of the periods studied, including in the 2006–2007 Constituent Assembly, have tended to vote as a bloc.

Meanwhile, in Ecuador, Indigenous interests were long represented by the dominant CONAIE and its political arm, Pachakutik. That union has come apart, however, as President Correa seeks to mobilize support of Indigenous voters through his Alianza País party. While Pachakutik supported Correa when he first ran in 2006—as it did with Lucio Gutiérrez before him—it has since broken with him, splintering the Indigenous political movement and for the first time presenting a challenge to the unitary claims of CONAIE and Pachakutik to represent Ecuador’s Indigenous peoples. And in the 2009–2013 National Assembly, for the first time Indigenous representatives in the assembly failed to vote as a bloc in the approval of an Indigenous-sponsored bill—further reflecting the fracturing of Indigenous representation in the congress across the three parties, as well as the strength of the executive.

Electoral Systems

In theory, the allocation of reserved seats based on racial or minority status would suggest increased legislative representation of that group. In our research, only Colombia and Bolivia have such reserved seats; and in the case of Colombia, it has proved a double-edged sword. (In the case of Bolivia, it is still too early to measure the broader effects on the party system and in the legislative process).

In Colombia, the national reserved seats have tended to fragment the Afro-Colombian vote, with up to 65 small parties competing for the two reserved seats in the Chamber of Deputies. In addition, as the seats have created a separate channel for representation of Afro-Colombian interests, traditional or national parties now have even less incentive to court Afro-Colombian votes. The net result has been the legislative marginalization of the caucus in both houses.

Colombian Indigenous representatives—with only one seat in the Chamber and two in the Senate—have fared only slightly better, electing one representative from a non-Indigenous party and enjoying greater consistency across elections in terms of the parties placing candidates for elections.

Nonetheless—and not coincidentally—Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives in Colombia have the lowest bill approval rate (though the highest attempt rate) among the four countries studied.

Executive–Legislative Relations

Given the hyper-presidentialism that has characterized contemporary Latin American democracy, it is impossible to discuss substantive representation—or any kind of legislative representation for that matter—without bringing in executive–legislative relations. Indeed, in all four cases, the success of the Indigenous or Afro-descendant agendas in congress remains highly contingent on the political interests, discretion and agenda of the president and his cabinet.

In Bolivia, the president’s power over legislative activity weighs particularly heavily. President Morales’ party held a majority in the constituent assembly and currently enjoys a supermajority in both houses. Consequently, insofar as MAS identifies itself as an Indigenous party representing Indigenous issues, the executive will continue to drive the agenda, irrespective of the individual interests and activities of Indigenous legislators.

In Colombia, the executive—either the president or his ministers—has had a hand in each of the laws relating to either Indigenous or Afro-Colombian issues. The 2010 Law of Native Languages was in large part the result of the initiative of then-Minister of Culture Paula Marcela Moreno, the first Afro-Colombian to occupy a cabinet position in Colombia. Similarly, the 2011 Law of Anti-Discrimination finally came about as a result of President Juan Manuel Santos’ interest.

In Ecuador under President Correa, the importance of the executive is even more obvious and potentially detrimental to the Indigenous agenda. As control of the Indigenous agenda has slipped away from CONAIE/Pachakutik, and the political rivalry between it and President Correa has increased, the legislature has become paralyzed on a number of efforts necessary to protect Indigenous rights. Two bills with serious ramifications for the Indigenous community (one on mining and one on water) have been proposed by the executive branch (the former approved). Both would violate territorial rights and essentially skip the process of prior consultation.

Further evidence of the importance of executive support for Indigenous and Afro-descendant rights comes from the two constitutional reform processes in Bolivia and Ecuador. While these constitutions and the processes that created them have generated considerable criticism, in both cases the constituent assemblies at the time were a high-water mark for Afro-descendant and Indigenous representation in the political process—and both were convened at the initiative of the executive.

In spite of a surge during the 1980s and 1990s in self-identification and organization along ethnic and racial lines and despite the resulting increase in the visibility of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples in the public and formal political institutions, representation of their interests remains low. The rate of participation of Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives in national legislatures doesn’t nearly reflect their composition in society at large. And much of their participation in legislative processes has been limited to symbolic agendas.

Their success in securing approval of the bills they do propose is largely dependent on support from international norms and bodies and on relations with the executive branch. As a result, Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives have passed few pieces of legislation that tangibly benefit their communities by addressing the root causes of their social exclusion—including lack of access to economic and educational opportunities and basic public services. Until this changes, Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples will remain effectively at the margins of society.

ENDNOTES:

1. All figures are from national census data: Bolivia (2001), Guatemala (2002), Ecuador (2010), Colombia (2005)

2. For detailed descriptions of the methodologies used to identify Indigenous and Afro-descendant representatives, please access the individual country reports available at: www.as-coa.org/socialinclusion.

3. Laly Catalina Peralta González, “Curules especiales para comunidades negras: ¿realidad o ilusión?,” Revista Estudios Socio-Juridicos 7 (2) (July-December 2005): 147-172.

4. Luis Alberto Tuaza Castro, “Cansancio organizativo,” in Carmen Martínez, ed., Repensando los movimientos indígenas (Quito: FL ACSO, 2009), 123-143.

5. Presidencia de la Repúblic, Ley de minería (Quito: Lexis, S.A., 2009).

6. Roddy Brett, “Los Retos para la Sociedad Civil en la Guatemala Postconflicto,” Red Nicaragüense por la Democracia y el Desarrollo Local, http://www.redlocalnicaragua.org (accessed December 7, 2012).

7. Ricardo Tejada Saenz, Elecciones, participación política y pueblo maya en Guatemala (Guatemala: Instituto de Gerencia Política, 2005.

8. Amy Atchison and Ian Down, “Women Cabinet Ministers and Female-Friendly Social Policy,” Poverty & Public Policy, 1(2) (2009): 1-25; Raghabendra Chattopadhyay and Esther Duflo, “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India,” Econometrica, 72(5) (2004):1409-1443; Miki Caul Kittilson, “Representing Women: The Adoption of Family Leave in Comparative Perspective,” The Journal of Politics, 70(2008): 323-334; Reingold and Smith (2010).