This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on peace and economic opportunity in Colombia | Leer en español

As far as the greater good is concerned, the benefits of Colombia’s peace deal are hard to deny. After more than half a century of war — and despite remaining divisions in Colombian society — one of the largest obstacles to long-term prosperity has been removed.

But reaping the economic benefits of peace — and securing the investment required to make sure it lasts — will not be easy.

Peace with the FARC will one day allow resources that were destined for arms to be dedicated instead to health, education and infrastructure. But that will take time. Military and police spending will not be reduced until the state has consolidated its presence in areas traditionally controlled by the guerillas, a process that will likely take at least five or 10 years.

In the meantime, the so-called peace dividend will not amount to much in macroeconomic terms, despite claims to the contrary from some analysts and official government entities. Yes, peace and security will attract tourism and productive investment in parts of the country that have long been dominated by armed conflict. But those zones are among the poorest and most isolated places in Colombia. Without minimizing the importance of peace for the people living there, the immediate macroeconomic impact of peace in rural communities will likely pass unnoticed by the economy at large. The most plausible estimates of the aggregate benefits of peace on GDP growth for the next few years are in the low tenths of a percentage point.

Even if the most optimistic assumptions about the peace dividend were true, Colombia’s macroeconomic outlook would present a challenge. There are two reasons. First is the precipitous fall in the international price of oil since 2014, which has greatly reduced the value of Colombia’s oil exports. The second is the recent economic fortune of Latin American economies that have traditionally been Colombia’s primary trade partners. The most extreme case is Venezuela, where accumulated economic contraction between 2014 and 2017 amounted to 30 percent of GDP in real terms, one of the worst economic depressions experienced by a medium or large economy in several decades.

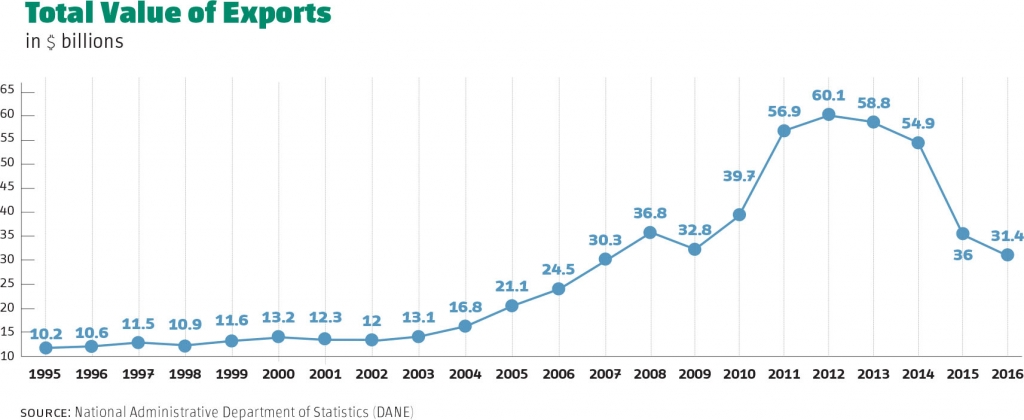

Taken together, the fall in the price of oil and the deterioration of neighboring economies led the value of Colombia’s exports to fall by 48.3 percent between 2013 and 2016 (see graph). A contraction of that magnitude has occurred only twice before in Colombia’s history. Both were atypically volatile times for the country: the War of 1,000 Days (1889–1902), when exports fell by 45 percent, and the Great Depression (1928–1932), when they fell by 49.8 percent.

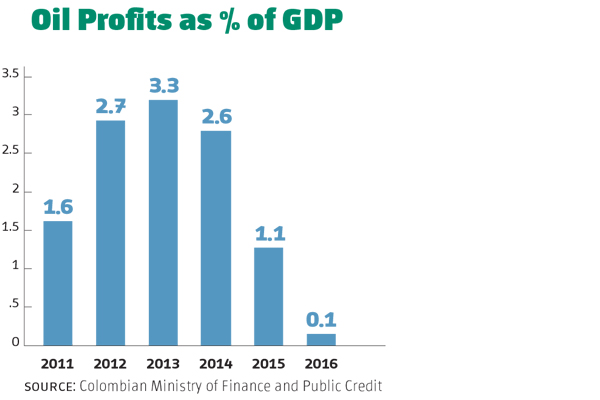

The fall in the price of oil has had a severe negative impact on Colombia’s fiscal health, too. Profits on oil received by the federal government — which includes taxes paid by businesses in the sector as well as dividends received by Ecopetrol, the state oil company — represented 3.3 percent of GDP in 2014. In 2016, the number practically was nil (see graph). The national government has lost a source of income that three years ago represented more than 20 percent of current revenues.

In that sense peace has come at a difficult time. The costs of rural development, strengthening infrastructure, and repaying victims of war — all included in the peace deal — could require net additional investment on the order of 0.6 percent of GDP for the next 15 years. Many wonder how the government will pay for it. Polarized opinions over the deal have led critics to argue that Colombia’s fiscal difficulties are a result of the demobilization itself.

That is not the case. The costs of reincorporating the guerrillas into civilian life, including the temporary stipends ex-combatants will receive, are marginal when viewed in macroeconomic terms. Those who view money directed at land reform, infrastructure to help farmers get their produce to market, and conflict reparations as “costs” in a traditional sense have further missed the mark. These are investments that Colombia must make in order to develop parts of the country that have for decades experienced a near total absence of the state. Whether or not the impetus for these investments was an agreement with the FARC is beside the point.

That won’t make paying for them any easier. Cuts will need to be made to other sectors so that resources can be assigned to rural development. That will require compromise, considering investment needs in areas like infrastructure, education and health, strengthening the justice system, and creating formal institutions in places that have been occupied by the guerrillas and other illegal forces.

The government will need to find ways to increase its earnings, which in turn will require a tax system that is both more progressive and better for competitiveness. Congress passed a major tax reform bill at the end of 2016. It was a step in the right direction, but incomplete. Further adjustment will be needed.

Either way, the difficult choices facing Colombia’s economy will only be palatable if cast in the light of a common vision, an opportunity for the country to unite around what it wants to be. Squabbling and political attacks are a distraction from the task at hand — and that task is already daunting enough.

—

Villar is the director of Fedesarrollo, one of Colombia’s most prestigious private research centers. Previously, he was chief economist and vice president of development strategies and public policy at the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF). He was also codirector of Colombia’s Central Bank from 1997 to 2009 and technical deputy of finance from 1994 to 1997.