In her final speech before Peru’s presidential election in April 2016, then 35-year old congresswoman Verónika Mendoza spelled out the choice facing voters: us or them.

“The usual politicians, the usual candidates,” she proclaimed. “Those who watch out for large companies in order to slip something into their pocketbooks.”

Mendoza finished third in the election, just over two percentage points short of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, who went on to defeat Keiko Fujimori in the runoff.

Fast forward to 2018, and Mendoza may be feeling something akin to vindication. The 2016 winner Kuczynski resigned amid allegations of corruption. Second place Keiko Fujimori sits behind bars, awaiting trial on corruption. Meanwhile, of Peru’s remaining living elected presidents, one is in jail, one is a fugitive in the U.S., and the third just had an asylum request denied by Uruguay.

Many expect Mendoza, who started her own party in 2017, to run for president again in 2021. While analysts say she’ll have a hard time as a leftist, recent polls put her approval on par with other presidential frontrunners.

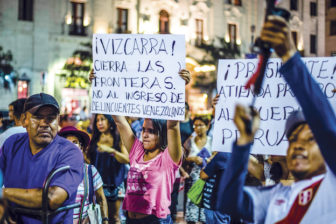

Mendoza is still speaking out against corruption, and threw her support behind President Martín Vizcarra’s historic anti-corruption referendum, set for Dec. 9. On the ballot are four reforms that would ensure greater transparency in party financing, revive the defunct Senate, ban consecutive congressional re-election, and reform how judges are elected.

Mendoza spoke to AQ about the significance of the referendum and the threats to Peru’s anti-corruption movement. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

AQ: The last year has been momentous for anti-corruption efforts in Peru. With Kuczynski’s resignation and the apparent collapse of Fujimorismo, do you think Peru has entered a new era?

Mendoza: Without a doubt. Currently, the last four presidents have been convicted or have been investigated for corruption. All of them, in addition to the leaders of the traditional business class. So that shows us that this is about more than the personal responsibilities of select individuals. This is about a system where the rules of the game have permitted and promoted corruption. Today, Peru faces a historic opportunity. There’s an opportunity to stir up politics and to investigate and sentence politicians. There’s also an opportunity to change the rules of the game so corruption doesn’t keep happening. We can change, for example, the perverse state contracting system, that, in the granting of large infrastructure projects, has generated a whole system of corruption involving large companies such as Odebrecht, OAS and many others.

AQ: Your Nuevo Perú party supported President Vizcarra’s effort to hold a referendum on four proposed anti-corruption reforms, and you’re asking supporters to vote in favor of three of them. Why is the referendum so important?

Mendoza: From the moment Vizcarra proposed the referendum, we backed it. We believe that in the context of a political crisis, with a congress that’s practically incapable of legislating, it’s necessary that the people have the say. And while we’ve pointed out that these proposed reforms alone are insufficient, they are a step toward deeper changes that we can debate after the referendum.

AQ: Of the four proposed reforms, which do you think has the most potential to transform the country?

Mendoza: Of the four, the most important seems to be the reform that would regulate party financing. We have advocated against political organizations directly purchasing their campaign advertising on radio and on television. The large part of the dirty money that’s entered politics in recent years ends up financing such campaigns.

AQ: Beyond the Dec. 9 referendum, what should be the government’s priorities in curbing corruption?

Mendoza: Political parties in Peru have turned into mafias or franchises that sell their seats to the highest bidder. So we need to reevaluate the rules for parties. This could mean current parties losing their registration. Let’s start over on new ground. Today the system is delegitimized and contaminated by corruption because everything is subject to the power of money rather than the will of the people and democracy.

AQ: What does Uruguay’s decision to not grant former President Alan García asylum mean for the anti-corruption movement?

Mendoza: Their decision affirms what we all know: Mr. García isn’t a victim of political persecution. It also allows Peru to keep investigating not just him but all the other political leaders that are currently indicted or under investigation. It would have been disastrous if Uruguay had considered granting García asylum.

AQ: Do you have hope for Peru’s anti-corruption fight?

Mendoza: It’s a historic opportunity, but at the same time, there are some concrete threats. The biggest is that attorney general Pedro Chavarry still has his job after allegations he was part of a criminal network. He has threatened prosecutors and judges who are investigating politicians that were once untouchable. The challenge for Peru is to bring the corrupt to justice, but we have to be vigilant. The corrupt still have their tentacles in the justice system.

—

O’Boyle is a senior editor of AQ.