This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on China and Latin America

Poetry night in Cidade de Deus. Up-and-coming authors and aspiring poets read work about race, violence and finding refuge in art — and try not to worry about the young men with guns standing two blocks away, guarding a drug stash house. After all, this is still the same City of God from the eponymous 2003 movie.

“In the middle of all this (violence), the favela launches books and creates paths of resistance,” Viviane Salles, a sociologist who was born and raised in Cidade de Deus, said onstage.

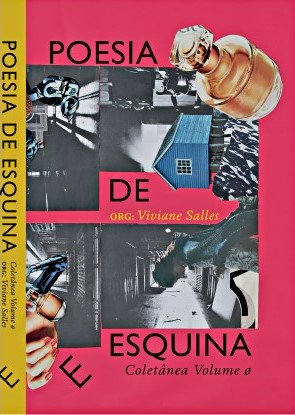

This was a special night for Salles: the launch of Poesia de Esquina (Corner Poetry), a collection of writing from local authors and the initial offering from Corner Editorial, the publishing house she first dreamed of nearly a decade ago.

The event breathed fresh air into a community long scarred by violence. In 2018, killings by police in Rio de Janeiro rose 35 percent as the state government confronted the city’s drug gangs in a hopeless attempt to limit their power.

The goal of Corner Editorial, Salles said, is to amplify the voices of authors from the slums and working class neighborhoods on the edges of Rio. One of those is Lindacy Menezes, 61, who has been a domestic worker since she was nine years old.

“Never in my life did I think I would become what I am today, a writer,” Menezes said after posing for a photo with the book’s authors. “I used to be a forgotten person, who wouldn’t speak, except to thank someone for telling me my cooking was good.”

Like Menezes, many of the contributors to Poesia de Esquina are ordinary figures in their community: street vendors, electricians and domestic workers who have discovered their inner artist at poetry events held in local bars and public schools. Others, like Tuca Muniz, who published her first book of poetry last year, are quickly becoming established local writers.

Together, Salles hopes that the authors in Poesia de Esquina will inspire the next generation of poets from the favela. Art has always been an essential part of life in Rio’s poor communities. Samba and, more recently, Brazilian funk were created here, and songs of the favelas have traveled the world for decades. But literature and poetry have found less space to thrive.

Salles’ launch event was part of a wider effort to change that. Three authors and a local film director spoke to the crowd about how to stimulate interest in poetry and reading in the favela. Among them was Jessé Andarilho, a writer from the Antares favela who has published two critically acclaimed novels, the first of which he wrote bit-by-bit on his cell phone while on his way to work.

“In the favela, I didn’t see anyone reading books,” Andarilho told the crowd. What caught his attention instead were drug dealers with shiny gold necklaces and heavy rifles. Meeting people who also liked literature and poetry made all the difference.

“These guys are doing cool things and they are going to live way longer, you know? This is the path I want,” Andarilho said.

With Corner Editorial, Salles said she hopes to provide an outlet for self-expression amid unthinkable hardship. While people from the favela don’t often buy books, she said, poetry is already present in their everyday lives.

“What you notice is that people of all ages, all social classes, have contact with poetry quite early in their lives,” she said. “They start writing poetry to pour out their feelings. Poetry is common and very present. But then it gets lost.”

—

Andreoni is a freelance reporter based in Brazil