As schools gradually reopen around the world, two questions are at the front of educators’ minds: How much ground did students lose during more than 20 months of pandemic-imposed closures, and how can policymakers close the learning gap?

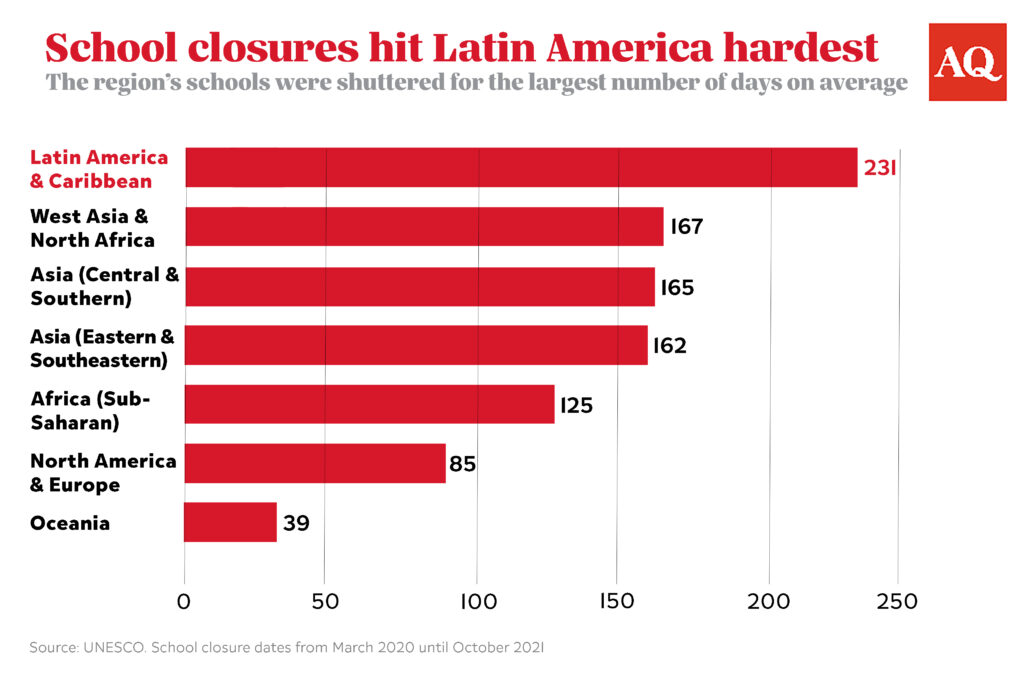

In Latin America and the Caribbean, both questions are just starting to be answered. Schools in the region were closed for an average of 231 days prior to October 2021, longer than any other part of the world. Teachers and parents made heroic efforts to ensure that students still received some level of learning. Education ministries broadcast lessons on radio and TV, expanded educational websites and used text messaging to send homework. In low-income households, children took turns doing lessons on a relative’s smartphone or shared printed handouts with their siblings.

But even as the region’s governments reported that school enrollment rates remained stable throughout 2020, they had little evidence of whether students were engaged in meaningful learning activities.

To assist policymakers, the Inter-American Development Bank, where I serve as chief of the education division, conducted an in-depth study of schooling indicators in 11 Latin American countries that together represent 83% of the students in the region. This was the first effort to analyze vast datasets from periodic household surveys in which parents or guardians answer questions about school-aged persons under their care.

We found that in large countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and Peru, between 30% and 50% of students between the ages of 6 and 23 participated in no learning activities or had no interaction with teachers during school closures. Given that these are among the wealthier countries in the region, we can assume that the situation is even worse in poorer countries for which detailed data is not available. This suggests roughly half of all students in the region were disconnected from learning during much of the lockdowns. Students were affected differently depending on income and geography. In rural Peru only 11% of households reported having access to online learning platforms, while in Bolivia, 42% of students in primary school could not study because they did not have a computer, tablet or cellphone. In contrast, 86% of primary school teachers in Uruguay reported providing lessons online during the pandemic.

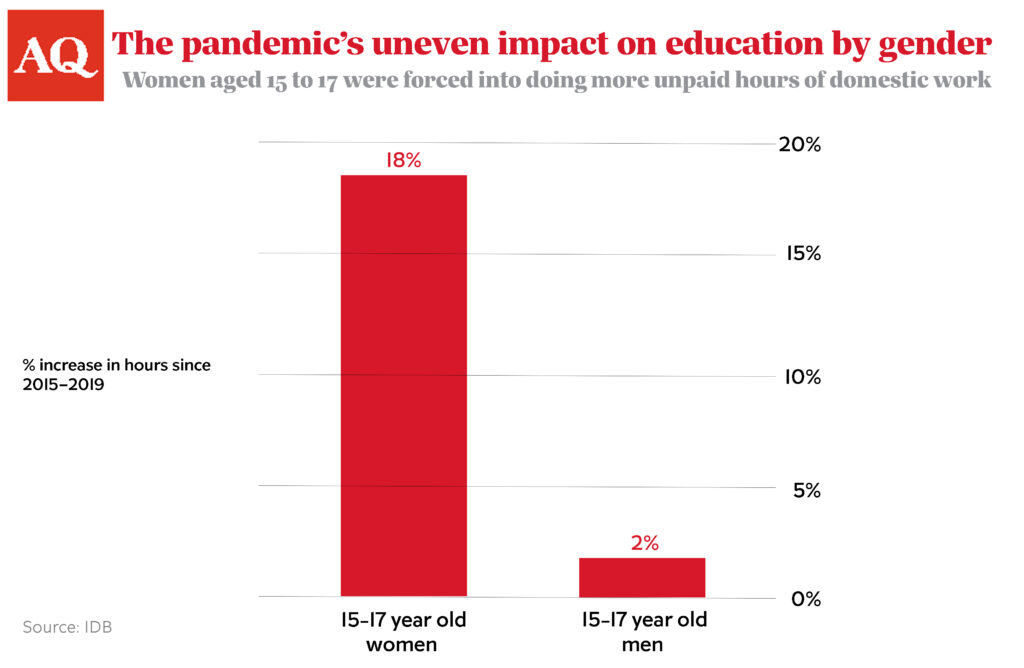

There is also evidence that the pandemic has been particularly damaging for young women. In Mexico, for example, the number of hours that 15- to 17-year-old girls devoted to household activities like cleaning, cooking or caring for children and the elderly increased by 18% during the lockdowns, compared to just 2% for young men. This represents a tragic reversal of decades of sustained progress in narrowing the education gender gap in the region.

The only way to know how these interruptions affected what students learned during the pandemic, along with how this will affect their long-term progress, is to conduct national assessment studies that can be compared to results from pre-pandemic tests. Only five Latin American and Caribbean countries managed to complete such evaluations in 2020, and just two — Brazil and Colombia —have so far published any findings. A study in São Paulo estimated learning losses equivalent to between one-half and two-thirds of a normal school year, with low-income students suffering most.

Research indicates that students who have missed more than half a year of school are at much higher risk of permanently abandoning their education. The risk is even higher for those whose parents lost their jobs. The lack of face-to-face contact with teachers and peers can create a self-reinforcing pattern of self-doubt and reluctance to study. In a region where, even before the pandemic, half of all students were not finishing secondary school, this vicious cycle could have calamitous long-term consequences.

Preventing mass dropout will require both immediate action and a long-term strategy. In the short term, it is imperative to reopen all schools and launch systematic efforts to trace and reengage with every single student. Administrators should prioritize the highest-risk students, using aggressive social interventions to ensure they return to class. Teachers should then evaluate the extent of learning losses and define customized remedial plans to help restore foundational learning skills. Well-evaluated social interventions in Colombia, Spain and other countries have shown that it is possible to narrow the learning gaps that were amplified during the lockdowns, reverse the downward spiral for struggling students and lend them confidence in their ability to learn and advance.

If they succeed in pulling children and youth back from the brink, the region’s school systems will be poised to undertake deeper transformations. The past year has revealed a huge hunger for change, along with vast reserves of resilience and creativity that should be channeled towards a new model of equitable education. The experience of the past 20 months has left governments better equipped to leverage technology to improve access and learning outcomes. But they must start by ensuring that none of their students are left behind by the pandemic.

—

Mateo-Berganza is chief of the education division of the Inter-American Development Bank.