CARTAGENA, Colombia — Everyone knew that strong challengers would emerge to compete with leftist frontrunner Gustavo Petro in Colombia’s May presidential race, but nobody expected Rodolfo Hernández to be one of them. The 76-year-old civil engineer from eastern Colombia has exploded on TikTok—and in the polls. A plain-spoken, cantankerous populist, he was virtually unknown on the national stage before this campaign; he was perhaps most famous for, as mayor of Bucaramanga, slapping a city councilman as cameras rolled for allegedly soliciting a bribe.

Hernández refuses to accept campaign donations or hold rallies, which he calls “prefabricated” events that “people are paid to attend”. Running as an independent, he also refused to participate in March’s center-left or center-right primaries despite the opportunity to gain broader exposure, insisting: “My only coalition is with the people.” Yet his simple messaging focused on anti-corruption—including his slogan “Don’t rob, don’t lie, don’t betray, and zero impunity”—appears to have broken through.

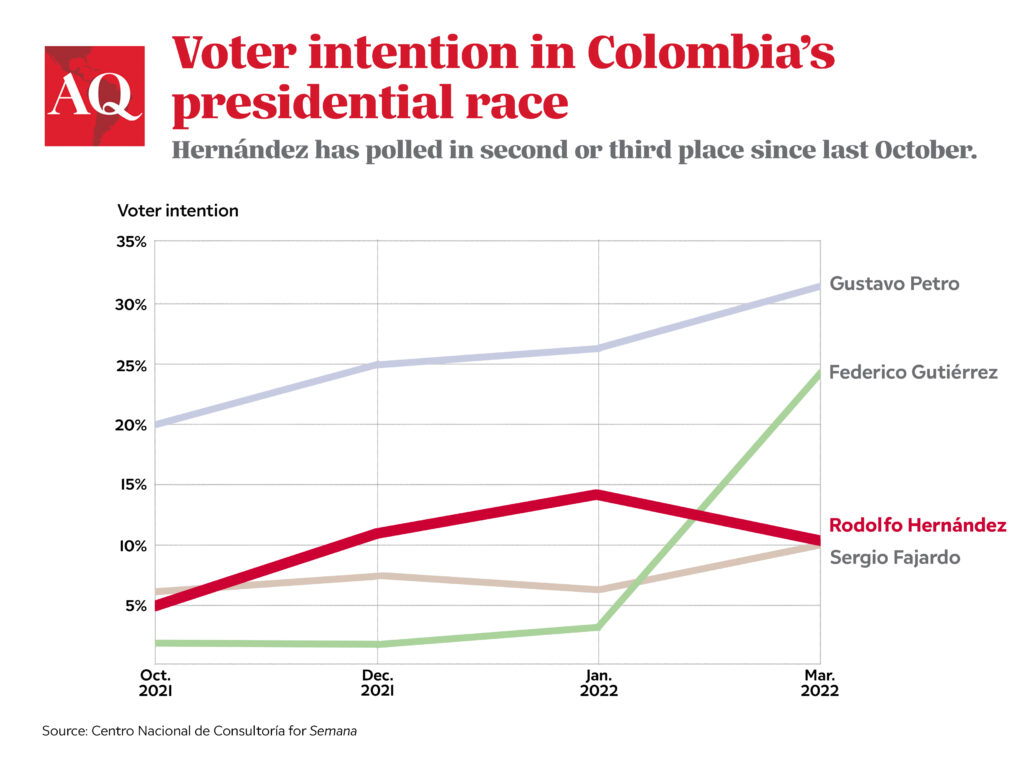

The latest polls have him in second or third place, and the septuagenarian is solidly the second-most popular candidate among youth ages 18 to 24. On TikTok, his videos have attracted over 1 million likes and earned him more followers there than any other candidate. He has also made waves for proposing to legalize cocaine, restore diplomatic relations with Venezuela and make peace with the ELN guerrilla group, which he believes abducted and murdered his daughter in 2004.

Petro remains the favorite in the race after the primaries, which also gave a boost to Federico “Fico” Gutiérrez on the right. But no one is discounting Hernández from making it to the second round—or at least becoming its kingmaker. “He’s growing exponentially, too much,” Petro’s campaign manager, Armando Benedetti, told me earlier this year. “He’s gathering votes of the right, and picking up some of Petro’s, too, because he’s anti-system.”

How did he achieve such a rapid rise to prominence? What does it tell us about Colombia’s national mood? What would he do if elected? AQ sat down with Hernández in February to find out, and he laid out a platform that was equal parts bold, unconventional and hard to decipher.

An opportune opening

For decades prior to this election cycle, Colombian elections were predictable enough, centered on the question of whether to pound the country’s insurgencies into submission or negotiate for peace. On the side of a crackdown was right-wing ex-President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010) and his followers. On the other side was a centrist and leftist opposition. Even after ex-President Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018) broke ranks with Uribe, his political mentor, and negotiated the 2016 Peace Accords with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the internal armed conflict still loomed large. The most recent presidential election in 2018 became a de facto referendum on the peace accords, propelling President Iván Duque, an Uribe ally, into office.

Then came the political earthquake of 2019, when hundreds of thousands of Colombians took to the streets to voice their anger on issues that had for years taken a back seat to the armed conflict: rampant corruption and impunity, ferocious income inequality and dwindling opportunities for young people. Mass protests flared back up in September 2020 over police brutality and again in April 2021 over Duque’s unpopular tax reform. Violent police crackdowns and counterattacks by protestors left dozens dead and hundreds detained, tortured or disappeared. Colombians’ outlook on the future darkened dramatically. Today, 85% say the country is heading in the wrong direction, the second-highest rate behind Peru among 28 countries surveyed by polling firm Ipsos.

Against this backdrop, all major candidates—left, right and center—have condemned the corrupt, clientelist machine politics that much of the public holds responsible for an unacceptable status quo. The problem is that almost all the candidates running are tied to the machine politics they vow to replace. Petro remains a solid 20 percent ahead of his nearest rivals, but he’s no political outsider, having served as a congressman, senator and mayor of Bogotá over the past 20 years. What’s more, he has now brokered alliances with an array of well-known machine politicians like ex-Antioquia Governor Luis Pérez and Senator Roy Barreras, raising doubts about his commitments to eschew vote-buying and backroom deal-making. Nor can centrist Fajardo easily tap into anti-establishment angst; he has already run for president once and now faces a controversial corruption investigation linked to his time as governor of Antioquia.

This has provided Hernández an opening. Arguably his most popular campaign slogan is “Neither Petro nor Uribe”; to Hernández, they’re equally in the wrong. As he explained: “Left and right is a way to distract the population so politicians can divide up the spoils and keep governing.”

The roots of Rodolfismo

Hernández has remained somewhat of a mystery even since his sudden surge to national fame, which was anything but preordained. Born in Piedecuesta, a small city in eastern Colombia, he grew up far from the country’s centers of power. After studying engineering at Colombia’s National University, he became a self-made millionaire, primarily by building housing for the poor and middle class. During the turbulent 1980s and 90s, he steered clear of ties to narco-traffickers and right-wing paramilitaries—unlike many of his peers—and gained a reputation as an honest job-creator.

Besides a short stint as a city councilor, he kept his distance from politics until 2013, when he began to consider a run for mayor of Bucaramanga, Santander’s capital. His brother, a reclusive Kantian philosopher, agreed to help, reportedly on two conditions: that Hernández not ally with Santander’s machine politicians and that he never buy a vote. Hernández agreed and launched a long-shot campaign, promising to build 20,000 houses for the poor if elected. Victory looked so unlikely that Hernández left the country on a rare trip abroad ahead of election day in 2015. When he got the news that he had won, he was stunned.

His time in city hall was polarizing, dramatic and—above all—popular. As mayor, he hosted his own public TV show to lambast corrupt politicians, and he clashed with the city council—literally. In an infamous episode, Hernández berated and then slapped a city councilor who had allegedly asked for a bribe (the councilor denied wrongdoing). Hernández focused, whether by choice or necessity, on pulling Bucaramanga out of debt. In the end he did not build any of the houses he had promised for the poor during his campaign. But the city’s residents don’t seem to have blamed him for it; Hernández left office with an 84% approval rating, one of the highest for an elected official anywhere in the country. Even an ongoing corruption investigation tied to a questionable contract designed by one of his sons hasn’t slowed Hernández down.

More questions than answers

When I met Hernández for an interview in Cartagena, I expected him to be flanked by an entourage, but he was sitting with his two sons and a handful of mostly millennial advisors—half his campaign team, which numbers just eight. He had come to the city to listen to a group of politically independent businesspeople, he emphasized, not to meet politicians or hold rallies. Unlike his larger-than-life, brash media persona, the real-life Hernández spoke softly.

Corruption, Hernández said, was the root of the country’s problems. Hernández drew a straight line from corruption and impunity to the 22 million Colombians, nearly half the population, who endure food insecurity and the millions more living in poverty. “After we take the checkbooks away from the robbers, we will start to generate funds,” he explained.

In his view, politicians and public contractors have colluded to capture the Colombian state. “Because most candidates don’t have the financial means (to run for office), they have to search out business partners,” he explained, “and these partners, 99% of them, are self-interested.” Politicians then rig public contracts to benefit their campaign financiers, generating a vicious cycle. “We’re breaking this system and trying to get elected not with money, but with emotions, feelings, communication,” he said. Hernández has insisted that he will not accept campaign donations from anyone, and by the looks of his personal fortune and threadbare campaign, this pledge seems credible.

But his policy proposals to root out corruption are less so. He has promised to revise all major public contracts immediately. “As soon as I win the presidency, I’ll call the contractors, the ones implicated (in alleged corruption schemes), and say … it’s on you to correct this,” he said. He did not, however, explain why the contractors would “correct” the situation. As for the judiciary, Hernández derided it for its slowness, musing, “As head of state, one needs to demand results.” He did not, however, offer specific proposals for judicial reform.

His economic proposals, meanwhile, sounded more like those of the populists of yesteryear—think Juan Domingo Perón or Getulio Vargas—than those of a 21st-century planner. “No more selling primary materials, commodities,” Hernández intoned. “Let’s sell finished products.” He then described a scheme to subsidize industry and agriculture, but it was unclear how he’d ensure that the subsidies would promote competitiveness as opposed to graft and sluggish, state-dependent industry.

On the 2016 Peace Accords, his posture might surprise, given his family’s suffering at the hands of guerrilla groups. Hernández’s father was held for months by the FARC, and he blames the ELN for his daughter’s disappearance in 2004 while traveling through ELN-controlled territory. Yet he proposes negotiations with the ELN similar to those held with the FARC. He also condemned the Duque administration’s slow implementation of the Peace Accords. When he told the story of visiting an underfunded camp for demobilized FARC militants in César, he lamented, “What a shame all the money the donor countries gave us for these demobilization camps, when Colombian politicians have robbed so much and made a joke of the Accords.”

A soft spot for Bukele

Hernández was equally strident on foreign policy. He has pledged to restore diplomatic relations with Venezuela, not out of any sympathy for dictator Nicolás Maduro, but to better serve Colombians living in the country. When asked about Colombia’s relations with the United States, he said he welcomes “everything the United States can do for international trade, to make us more competitive.” But he insisted, “We prefer that you don’t put shackles on us in terms of the exports we produce.” He was also frank about his distaste for the status quo approach to counter-narcotics. “The recipe we’ve accepted, that the U.S. has offered, doesn’t work,” he said, proposing full-scale legalization of cocaine instead.

The conversation took a turn when Hernández discussed Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, doing nothing to hide his admiration. Hernández glowed when he described his recent trip to El Salvador. “Why should we value the democracy of thieves that was there (in El Salvador before)?” he asked, marveling at Bukele’s sweeping power. He even endorsed Bukele’s decision to send the military into El Salvador’s legislature during a critical vote in early 2020, a move that earned international condemnation and fanned worries of authoritarianism. “It got the job done,” Hernández said, adding that no one was physically hurt.

His connection to Bukele goes beyond the superficial; Hernández for a time worked with the Spanish political strategist Victor López, who also worked on Bukele’s 2019 presidential campaign. “If the opposition can’t find an argument, you (as president) have a ‘demolishing power,’” he explained, implying that Colombia might need some demolition work of its own. So far, this kind of praise for strongmen hasn’t seemed to cost him much public support—another sign of the Colombian public’s lack of enthusiasm for the country’s political institutions.

As we wrapped up the interview, Hernández invited me to visit a model home for the poor he had built in the central square of his hometown Piedecuesta. He took out his phone and flicked through pictures of the house, which looked vaguely like a spaceship. You couldn’t miss the irony; the home was complete but uninhabited, while the thousands of units Hernández promised before becoming mayor had never materialized.

Colombia’s pressing economic, social and political problems could use a capable engineer ready to mend the cracks in the country’s foundations. But, as with the other top presidential contenders, it’s not yet clear whether Hernández is up to the task.

—

Will Freeman is a Ph.D. candidate in politics at Princeton University.