While tweets and speeches may continue to cause consternation in Mexico and Canada, the existential threat to NAFTA seems to have passed.

President Donald Trump is now talking about giving “renegotiation a good, strong shot” rather than rescinding the free trade agreement entirely. On the docket will be intellectual property, labor rights, e-commerce, rules of origin and the environment – issues Canada and Mexico are happy to upgrade, the outlines already defined within the ill-fated Trans-Pacific Partnership. More contentious issues could include “Buy American” clauses, border customs processes, sanitary measures, and import licenses, as well as specific grievances around the Canadian dairy and soft lumber industries, and regarding Mexican sugar imports. The process will undoubtedly be drawn out; the negotiations won’t begin in earnest until three months after the White House informs a still-waiting Congress.

But for Mexico, there is another huge challenge to its economic future: U.S. tax reform.

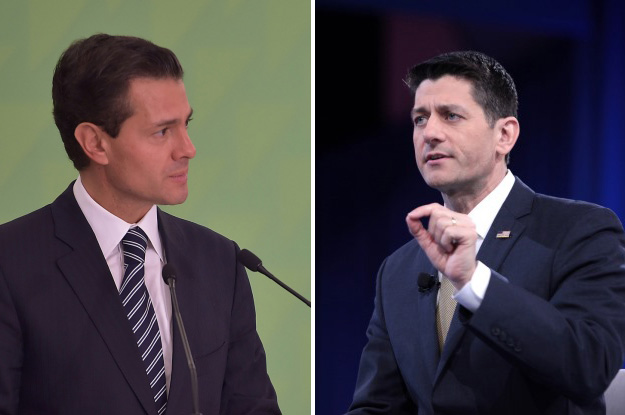

The most obvious and widely noticed threat is a border adjustment tax (BAT). As laid out in Speaker Paul Ryan’s tax reform “blueprint,” it would charge a 20 percent levy on all goods and services brought into the United States, and exempt U.S.-made exports from being taxed at all. Its proponents claim the dollar would appreciate the 25 percent necessary to call it an economic wash; others believe Mexico and other exporting nations would suffer. This pseudo-value added tax (VAT) is looking less and less likely, as it is opposed by Wal-Mart, Target and nearly every other major retailer, as well as by oil companies, car makers and others that depend on products from elsewhere to run their factories and businesses here. Even if it passes, it will face legal challenges in the World Trade Organization (WTO) for its non-VAT qualities, in particular allowing companies to deduct wages when calculating their BAT tax burden.

A corporate tax cut is more likely to succeed, and could be as damaging for Mexico. Republicans across the board have long favored a reduction, and with the U.S.’ current 35 percent tax rate ranking highest among OECD nations, they have an argument for it. Ryan talks of lowering the corporate rate to 20 percent, bringing the United States in line with the United Kingdom and Luxemburg. Trump’s more drastic 15 percent proposal would put the United States in the bottom 20 percent of chargers, beating out Germany and closing in on the “corporate tax haven” of Ireland.

If the U.S. rate plummets, Mexico will be forced to follow suit. With its 30 percent corporate rate, Mexico is by far the highest charger among emerging OECD economies, and only slightly behind the three most expensive places to locate your business: the United States, France and Belgium. NAFTA has enabled these elevated rates, as companies accept Mexico’s high tax burden in return for the benefits of tariff-free market access across all of North America. Yet matching or undercutting the U.S. rate is necessary for Mexico to remain an attractive place for investment and companies.

This, in turn, will require hard financial and political choices to cut spending, take on debt or raise other taxes to compensate.

Cutting spending is always tough, and President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration in Mexico has never been able to come in on or under budget. During its first three years in office, the administration overspent on average more than $13 billion a year. In 2015, despite very public promises of austerity in the face of oil price declines, the government managed to outdo its previous profligacy, spending $14 billion more than it was authorized. And last year, in the face of heated gubernatorial elections, the government racked up $32 billion in extra expenses.

These outlays haven’t gone into roads, ports, or other long-term projects that could propel Mexico’s economy forward; infrastructure spending is at its lowest levels in decades. Instead, it is covering salaries, benefits, other current costs, and likely much of the money siphoned off by the 10 former governors now under investigation or indictment for corruption.

All this overspending has left Mexico far more indebted. When Peña took office, Mexico’s outstanding debts equaled roughly a third of its GDP. Today it is closer to one half. While still manageable, these higher levels limit Mexico’s ability to float the Treasury billions in lost revenue from a potential corporate tax cut.

The final option is to raise other taxes to fill in for lower corporate rates. The Mexican government today leans heavily on its private sector to pay its bills, far more dependent on company-based levies than the United States or other Latin American countries. These taxes bring in roughly $30 billion a year – almost 1 in 5 pesos coming into the public treasury.

On the face of it, raising new revenues should be possible – Mexico collects just 17 percent of its GDP in taxes, the lowest in the OECD and lower than the Latin American average. Yet potential revenue sources – for instance expanding the VAT to include food and medicines – are political non-starters for the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Property taxes, which Mexico barely charges, would bring state and local governments into the collection process. And any shift would contradict the “no new taxes” promise made during the 2014 fiscal reform process.

The biggest problem for Mexico is how much of its economy is not taxed at all. Next to convenience stores stand individuals selling candy, gum and other products for sale inside. Outside restaurants are makeshift stoves cooking up lunches of steak tacos, tamales, or pozole, and accompanied by homemade horchata, a popular rice based drink. At stoplights one can buy everything from oranges to coat hangers, soccer jerseys to figurines of the Virgin of Guadalupe. None of these street vendors pay corporate or other taxes. And even well-heeled locales often don’t pay their full burden. Restaurants, stores and hotels routinely offer discounts for cash, suggesting, if not outright acknowledging, the routine dodging of the SAT, Mexico’s tax authority. With nearly a quarter of the nation’s GDP beyond the reach of the state, increases in nominal tax rates incentivize even more workers and firms to stay or move into the legal shadows.

Mexico can ill afford to lower its corporate tax intake. Yet if the nation doesn’t follow its neighbor, it will lose revenue anyway. Multinationals will move their headquarters north, shrinking the overall tax base.

If the Trump administration succeeds, these difficult tradeoffs will fall on a lame-duck president, negotiating a final budget even as Peña prepares the presidential resience of Los Pinos for its next occupant in 2018. He or she may then find that NAFTA is the lesser economic worry concerning their neighbor to the north.