This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Lula and Latin America

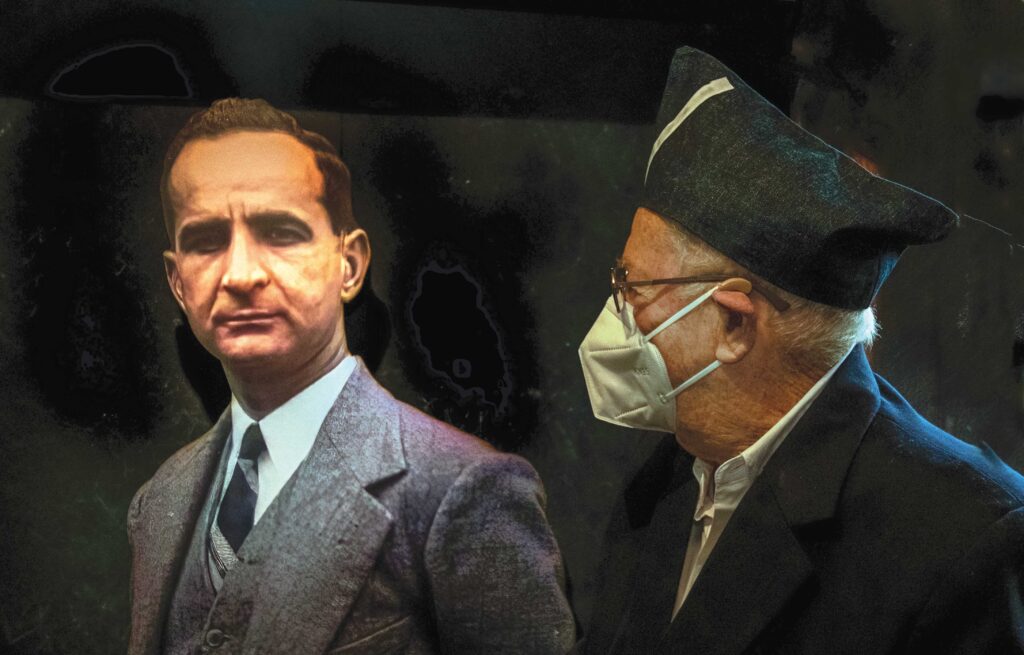

SAN JOSÉ, Costa Rica — As in the rest of the Americas, Costa Rica’s armed forces played an important role in building its state infrastructure and creating a sense of nationhood. From defeating an 1857 pirate invasion led by William Walker, to what would be the country’s last military coup in 1917, the military were front and center in the country’s political life. So that made it all the more momentous when on December 1, 1948, the then-leader of the governing junta, José Figueres Ferrer, issued a declaration abolishing the armed forces.

Within a year, the decision had been codified in the country’s constitution.

In a region characterized by the political prominence of its militaries even today, it is natural to ask: How did this happen? Looking back at the chain of events that led to Figueres’ decision, one thing is clear: A key motive was not lofty pacifist principle, but rather taking advantage of a weakened military in order to eliminate it as a potential political rival.

The beginning of the end of Costa Rica’s armed forces can be traced back to a 1917 coup d’état by General Brigadier Federico Tinoco. Refused recognition by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, Tinoco’s regime languished in international isolation, while his repressive policies were extremely unpopular among all sectors of Costa Rican society, including the powerful coffee exporters. Within two years, the dictator had lost support from economic elites and even the army itself. After Tinoco’s brother, the war minister, was assassinated in 1919, he fled the country.

The resulting political consensus among the ruling elite was to sideline the army and strengthen civilian control over the military. Gradually, the army’s budget was reduced. As defense expenses dwindled, public education and police budgets increased. From 1920 to 1948, Costa Ricans elected seven civilian presidents, and though voting was a male prerogative, all in all, elections were reasonably free and fair.

But between 1940 and 1948, the country experienced intense political polarization. The social reforms of Christian democratic President Rafael Calderón Guardia—backed by a coalition ranging from the Catholic hierarchy to communists—drew ferocious opposition from commodity exporters, the business community and anticommunist activists, who began taking up arms.

Calderón lost reelection in February 1948, but had Congress annul the result—at which point a group of young intellectuals, supported by a sector of the ruling elite, formed a rebel army and marched on the capital, demanding that the outcome of the popular vote be respected. Their National Liberation Army, under the leadership of José Figueres Ferrer—a coffee grower of Spanish origin—defeated the badly organized and poorly equipped governmental armed forces, which had been defunded since the demise of the last military coup.

As leader of the resulting junta, in a surprise move, Figueres consolidated Calderón’s progressive social reforms—even going further, nationalizing banks and insurance companies, introducing suffrage for women and full citizenship for Costa Ricans of African descent. And—he disbanded the defeated armed forces, as well as his own troops, in order to guarantee civilian rule in the future. Not only was Figueres shielding future civilian governments from potential threats, he was also freeing up resources for public education and health care.

After Figueres’ junta handed power to elected officials, he would serve as president twice: in 1953-57 and in 1970-74. His experiment with abolishing the armed forces has lasted seven decades.

Geopolitics helped

The country’s domestic political dynamics from 1920 onwards were crucial in the abolition of the armed forces in Costa Rica. But it is also important to consider other factors, of an international and geopolitical nature.

The international system was changing dramatically after the Allied victory in World War II. Promoted by Washington, a rules-based international order was taking shape. On April 25, 1945, 50 governments met in San Francisco and started drafting the UN Charter. According to its Charter, the organization’s purpose is to maintain peace and security, protect human rights, deliver humanitarian aid, promote sustainable development, and uphold international law. At its creation, the UN had 51 member states representing most of the world’s sovereign states at the time—and 20 were Latin American. Today it includes 193 members, 31 from the Americas.

And some of the first international organizations of the new world order led by Washington were born in the Western Hemisphere. The Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, also known as the Rio Treaty or TIAR by its Spanish acronym, was signed in 1947, the first of the mutual security agreements created during the postwar era—though it soon became a Cold War instrument invoked mainly against perceived communist menaces. The Organization of American States (OAS) was established a year later in Bogotá, with the purpose of increasing cooperation among the American states and strengthening their territorial integrity.

The Costa Rican elites counted on these mechanisms to ensure their security vis-à-vis their neighbors, in particular their northern neighbor, Nicaragua. As a matter of fact, the OAS has been called to mediate between the two countries in 1949, 1955 and during the Central American conflicts of the 1980s.

For the small Central American and Caribbean countries on the United States’ periphery, the most important threat to their national security had traditionally been Washington’s policies and armed interventions. Historically, this has not been an idle threat. During the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. temporarily occupied many of them militarily. But having a powerful military is of little use in this regard: The power asymmetry is so overwhelming between the U.S. and the Caribbean Basin small states that military resistance would be futile. Costa Rica was not occupied, but neighboring Nicaragua and Honduras endured foreign troops on their soil and intervention in their customs offices. In Panama, the U.S. manned the canal until 1999 and administered a small colony in the Canal Zone until 1979.

The international organizations created after World War II fulfill two roles. They increase the costs of military interventions by great powers, but do not deter these interventions altogether. However, they also serve as collective security mechanisms for small and medium-sized states. In the Americas, they do not impede Washington’s direct or indirect interventions in Central America and the Caribbean—but the collective security mechanism did serve its purpose.

Not unarmed

Instead of a standing army, Costa Rica’s civilian authorities created three corps: a civil guard, a rural guard and a short-lived military police that was later subsumed into the police force. In 1996, following an important security reform, the civil and rural guards were reorganized under the public security ministry into three commands: land, sea and air. The Costa Rican public security forces are responsible for assuring border security, combating narcotrafficking and organized crime and fighting crime in general.

It’s also worth noting the 1949 Constitution bans the existence of a permanent force but does not preclude the formation of temporary military forces. The Costa Rican Congress, following a national emergency declaration, could authorize the recruitment and training of a temporary force in case of imminent danger.

What’s been the regional legacy of Costa Rica’s shedding of its military? As of today, six sovereign states in the Americas have chosen to follow the Costa Rican example: Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Haiti and Panama. The first four are members of the Caribbean Regional Security System, which works closely with the U.S. Southern Command. Haiti and Panama, in contrast, have small paramilitary forces.

Other parts of the region have been moving in the opposite direction. In Mexico, for example, the reach of the armed forces has lately expanded to include many domestic roles, from tourism to policing and infrastructure projects. In Brazil, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is seeking to deal with the fallout from the greatly expanded military presence in civilian government under his predecessor.

In these countries, the greatest threat isn’t the armed forces themselves but rather the worry that civilian control over them could be slipping. And there’s an irony for politicians like Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador: By increasing the armed forces’ participation in civilian affairs, they put in danger their own control over the military.

Of course, it’s no accident that the countries that have shed their militaries are all small countries. But even if countries like Mexico and Brazil can’t aspire to emulate Costa Rica in the short term, they can learn from other aspects of Costa Rica’s history—especially in how it demonstrates the importance of civilian control of the military.

__

Eguizábal is a political scientist and professor at the University of Costa Rica.