NEUQUÉN, Argentina — The debates and scandals around lockdowns and vaccines happening throughout Latin America have also plagued Argentina, where the pandemic has claimed the lives of over 110,000 people. Meanwhile, the economy is reeling from a 10% drop in GDP in 2020 and inflation and poverty rates over 40% — all as two polarizing ex-presidents vie for influence.

A reader might conclude that Argentina, which will hold midterm elections in November, is thus ripe for an explosion, especially considering how neighboring countries once lauded as stalwarts of stability, like Chile, Peru and Colombia, have fallen into political crises and social unrest. But as campaigns gear up, Argentina’s political system is surprisingly calm.

Once considered a basket case of instability, Argentina today has two stable political coalitions. On one side is the governing Frente de Todos (Everybody’s Front), a populist-leftist alliance representing the Peronist political movement. Its opposition is Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change), a liberal-conservative alliance organized by the Republican Proposal (PRO) party and the older Radical Civil Union (UCR) party — the coalition that elected Mauricio Macri in 2015. These two alliances accounted for 88% of the votes in the last election and continue to look sturdy as mid-terms approach — a surprising scenario in a country prone to crises and breakdowns since transitioning to democracy in 1983.

Indeed, memories are still fresh of the riots and protests that forced two democratically elected presidents to resign, first in 1989 and then in 2001, when Fernando de la Rúa’s exit sparked a succession of five presidents appointed by Congress in two weeks.

By 2003, when elections were finally held, the Argentine party system was in shreds. None of the six most-voted presidential candidates received more than 24% of the votes. Carlos Menem, who had finished first, shocked the country when he announced that he would not participate in the runoff election. The first-round runner-up, Néstor Kirchner, was sworn in by default — with only 22% of the vote.

The political shake-up continued as dozens of leading politicians created brand new parties, including former Menem allies protesting the rise of Néstor and his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Ambitious political entrepreneurs crossed over from business to politics and funded their own tailor-made political structures, including Macri. Congress became a patchwork of small political forces. The whole party system seemed irredeemably fragmented, and multiple figures competed for leadership.

Fast-forward twenty years, and Fernández de Kirchner’s Frente de Todos and Macri’s Juntos por el Cambio now dominate the political arena, each showing an unexpected level of resilience. Many expected they would, by now, have fallen apart. In the case of Juntos por el Cambio, the coalition formed in 2015 against the misgivings of some in the UCR with the goal to defeat Peronism. This led Macri to become the first non-Peronist and non-Radical president in over a century. However, Macri’s government ended in disappointment, and after he lost his reelection bid, some believed the older and more institutionalized UCR would leave the coalition and seek to reclaim its role as the sole opposition. This has not happened.

Equally surprising is the fact that the Frente de Todos has stayed in one piece. The coalition was assembled three months before the 2019 elections uniting most of the Peronist fractions that had splintered years earlier. Leaders such as Sergio Massa, Roberto Lavagna and even now President Alberto Fernández himself, who had left mainstream Peronism in dissatisfaction with Fernández de Kirchner’s personalistic style of leadership, came back into the fold after failing to defeat her in the polls or grow their own parties. Analysts thought that the uneasy alliance would crumble under the weight of COVID and the economic downturn, or because of scandals like the recent birthday party for the first lady at the presidential residence that many saw as flouting social distancing. But for now, the Frente de Todos is united heading into November’s election.

Several factors have been key in keeping these coalitions intact. Two are institutional, the first being the fact that Argentina has never allowed independent candidates, and electoral laws and organization incentivize the creation of parties. The second one is a law passed in 2009 that mandates simultaneous primary elections for all parties seeking to compete in national elections and encourages competition within coalitions.

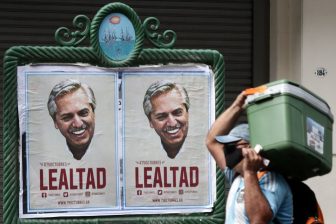

Two other reasons for the coalitions’ strength are less easily defined. The first one is political polarization. Any issue that arises in Argentine politics, from taxes to gender rights to COVID measures, gets subsumed into the Peronist government vs. anti-Peronist opposition dynamic. If one side is for something, the other side is against it, and vice versa. So far, polarization has helped uphold the dual-coalitional nature of Argentina’s political system. The second factor is the role played by Macri and Fernández de Kirchner in keeping their respective coalitions together.

Since 2007, the dispute between the two leaders has defined Argentine politics. Macri and Fernández de Kirchner’s personalities and ideologies could not be more different, but both ruled their own coalitions with an iron fist, building a strong, deep emotional connection with their core supporters. Each commands the support of a substantial block of voters — but are also rejected by a similar fraction of the voting population. This dynamic has forced them to welcome allies as well as would-be rivals into their coalitions.

For her part, Fernández de Kirchner chose not to run in 2019, and handpicked Alberto Fernández (no relation) to be her coalition’s candidate. While many expected her to challenge Alberto, she has remained on the sidelines so far. The order of candidates on lists for November’s election were quietly negotiated between the two and her one-time critic Massa and approved without much fuss.

Meanwhile, given Macri’s low poll numbers and his coalition partners’ eagerness to move forward to the 2023 presidential election, he appears increasingly willing to pass the baton to would-be successor Buenos Aires Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta — after some hesitancy. This would go a long way in further transforming Juntos por el Cambio from a personal brand to an institutionalized coalition.

One should be careful to note, however, that the current state of stability is by no means assured to last. It might very well be that the next two years before the general election are just the calm before the storm. If the economic situation does not improve rapidly for most Argentines, if more scandals emerge, and if deaths from COVID spike dramatically due to the Delta strain, the situation could change, and even deteriorate, rapidly. As it is, both the government and the opposition are taking it one day at a time.

—

Casullo is a political scientist and professor at the National University of Río Negro. She is the author of Por Qué Funciona El Populismo? (Why Does Populism Work?).