PANAMA CITY — Ever since President Donald Trump first aired his grievances about the Panama Canal in December, the establishment here and indeed throughout the Americas has been engaged in the same guessing game: “What does he really want?”

At first, the question was met with a certain knowing wink: This is what Trump does, opening a negotiation by pounding the table. But after the president of the United States explicitly said in his inauguration speech on Jan. 20 that he wants the canal back, opening the door to a new era of American expansionism that also includes Greenland, calm has been replaced in Panama by a mix of urgency, gallows humor and utter disbelief.

After spending several days in Panama City (a long-planned visit, though no one believed me) and meeting with local business and political leaders, four main theories emerged about Trump’s true endgame.

The first and most widely cited thesis revolves around 1) China — and here, many in Panama say Trump has a point.

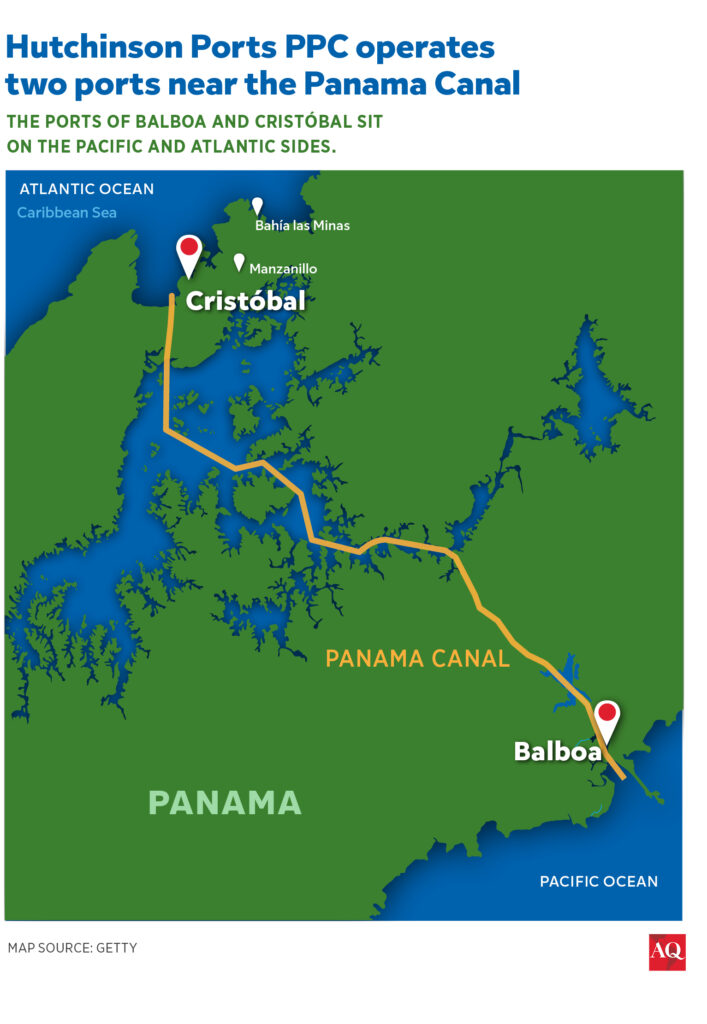

No, there are no Chinese troops in the Panama Canal, as Trump has claimed, nor any Chinese presence within the canal itself. But China arguably controls the biggest ports on either end of the canal via a subsidiary of Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings. Hutchison’s unit has administered the ports without incident since 1997, but the geopolitical equation changed after Hong Kong lost any pretense of autonomy in recent years. General Laura Richardson, until recently the head of the U.S. military’s Southern Command, repeatedly warned that China could repurpose the ports for military use or otherwise use them to disrupt canal traffic in the event of a conflict.

Some Panamanians downplay this risk. Other observers may dismiss it as yet another American delirium rooted in the 202-year-old Monroe Doctrine. But the Panama Canal receives about 40% of U.S. seaborne container traffic and 5% of global trade overall; any disruption would also cripple the U.S. Navy’s ability to move resources around the world. The idea that the canal is uniquely sensitive to U.S. national security, truly in a category of its own in Latin America, has been a core principle in Washington since the days of Theodore Roosevelt. Views of what is considered tolerable in terms of China’s presence have evolved in both Republican and Democratic policy circles, especially as Beijing has positioned itself near other global “chokepoints.” Trump and his team now appear to be using whatever leverage they have to shift that red line as they prepare for greater commercial, and possibly other, conflict with Beijing in years to come.

Trump’s tactics alienate people, and they may well erode U.S. alliances and, therefore interests, over time. However, the Panamanian government now appears to be dialing back a broad expansion of ties with Beijing that dates back to 2017, when then-President Juan Carlos Varela switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China. Ensuing years saw Panama join China’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative; host a visit by Xi Jinping; acquire Chinese “safe city” technology; and even authorize the construction of a new Chinese embassy near the entrance to the canal, before canceling the plan under U.S. and domestic pressure.

Since Trump’s election, President José Raúl Mulino’s government has announced an audit of the Hutchison port concession, which some locals say was extended under less than transparent circumstances in 2021. Mulino has also hired AECOM, a U.S. company, to oversee a planned $4 billion intercity train that previously attracted Chinese interest. “You’re a company recognized globally, a 100% American company,” Mulino said at a ceremony Monday, adding with a smile: “I hope no Chinese show up over there.”

Several business leaders I spoke to said that in retrospect such a deep embrace of Beijing was bound to cause trouble. “We are paying the price for 25 years of a lack of strategic thinking,” Alonso Illueca, a Panamanian lawyer who has written extensively on Chinese ties, told me. “That may now be changing.”

The second explanation for Trump’s threats revolves around 2) migration, and here, the outlook is mixed. Mulino made stopping migration through the Darien Gap a centerpiece of his 2024 campaign, even before Trump was elected. He has referred to Panama as the U.S.’s “other border” and seems eager to work with Washington to toughen enforcement further. But if Trump wants Panama to receive immigrants from third countries like Venezuela, as some U.S. officials have suggested, he will face resistance. Bad memories remain from a similar arrangement in the 1990s, when Panama temporarily sheltered thousands of Cuban refugees, and riots broke out. The country has already absorbed large numbers of immigrants in recent years. “It’s politically impossible,” for Mulino, one observer said. “It could crash the government.”

The third theory centers on 3) transit fees through the canal. Local officials dispute Trump’s claim that U.S. Navy and other ships are paying higher fees than anyone else. They say an increase in fees in 2024 resulted instead from a historic drought that forced the canal to reduce traffic, putting reservations at a premium. Panama is barred by treaty from giving preferential rates to any specific country. However, some believe that authorities could waive fees for U.S. Navy vessels on security grounds as a gesture to Trump.

The final and most problematic possible explanation is that 4) Trump really does want the canal back.

Everyone in Panama noticed that Trump used his inaugural speech, rather than just another appearance on Fox and Friends, to declare his intentions for the canal. While some saw it as a classic Trump tactic, a maximalist position to open a negotiation, others note he preceded his remarks about Panama by extolling former U.S. President William McKinley, who oversaw the last period of major American territorial expansion in the 1890s. Trump may believe that Making America Great Again implies a return to those ambitions, just as it involves getting to Mars with the help of Elon Musk. Trump may also see this as the best path to a superlative legacy — and perhaps to having a mountain named after himself, as McKinley (once again) does.

Mulino has steadfastly rejected Trump’s advances, repeating Wednesday that the canal “is and always will be Panamanian.” On that point, he has overwhelming domestic support: Omar Torrijos, who signed the 1977 handover treaty, famously called the canal “the religion that unites all Panamanians.” But locals still worry that Washington could put enormous pressure on Panama without deploying a single U.S. troop. Panama is a dollarized economy and a major financial center, making it especially vulnerable to tariffs and Treasury Department sanctions like the ones Trump threatened against Colombia’s government this week. “He just showed us his arsenal,” one Panamanian executive noted.

Mauricio Valenzuela/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Locals also darkly wonder if there is a personal element to Trump’s actions. Panama was the site of one of his company’s most ill-fated recent ventures, a hotel that local police entered and confiscated in 2018 following a dispute with another investor. His complaints about the canal handover go back at least a decade. “Trump knows Panama well,” Rodrigo Noriega, a political analyst, told me. “He knows how things work here. He knows where the pressure points are for the local elites.”

Whether Trump is motivated by one or two of these reasons or a combination of all four, Panama faces an uncertain and dangerous road. Ahead of a visit by Secretary of State Marco Rubio scheduled for this weekend, local officials have moved to correct the factual record, hired lobbyists in D.C., filed a complaint with the United Nations, and called on allies in Washington and around the world to help support their cause. Ultimately, the prevailing view inside Panama is still that if they can sufficiently address concerns 1, 2 and 3, they will be able to avoid 4.

Considering Panama’s demonstrated willingness to act, I personally find it hard to imagine that Trump, even at the apex of his power, would be able to go too far down the path of forced confiscation without facing resistance from elsewhere in the Republican Party, and perhaps among some of his Cabinet and military advisers. One can envision Trump eventually declaring that he did “take the canal back” — from China — in the same way he has claimed Mexico ended up paying for the border wall.

But in a world that is changing by the hour, and where the president of the United States thinks not in terms of allies or norms but in terms of strength and weakness, what happens next is truly anybody’s guess. Which is probably just how Donald Trump wants it.

Subscribe to The Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, and other platforms