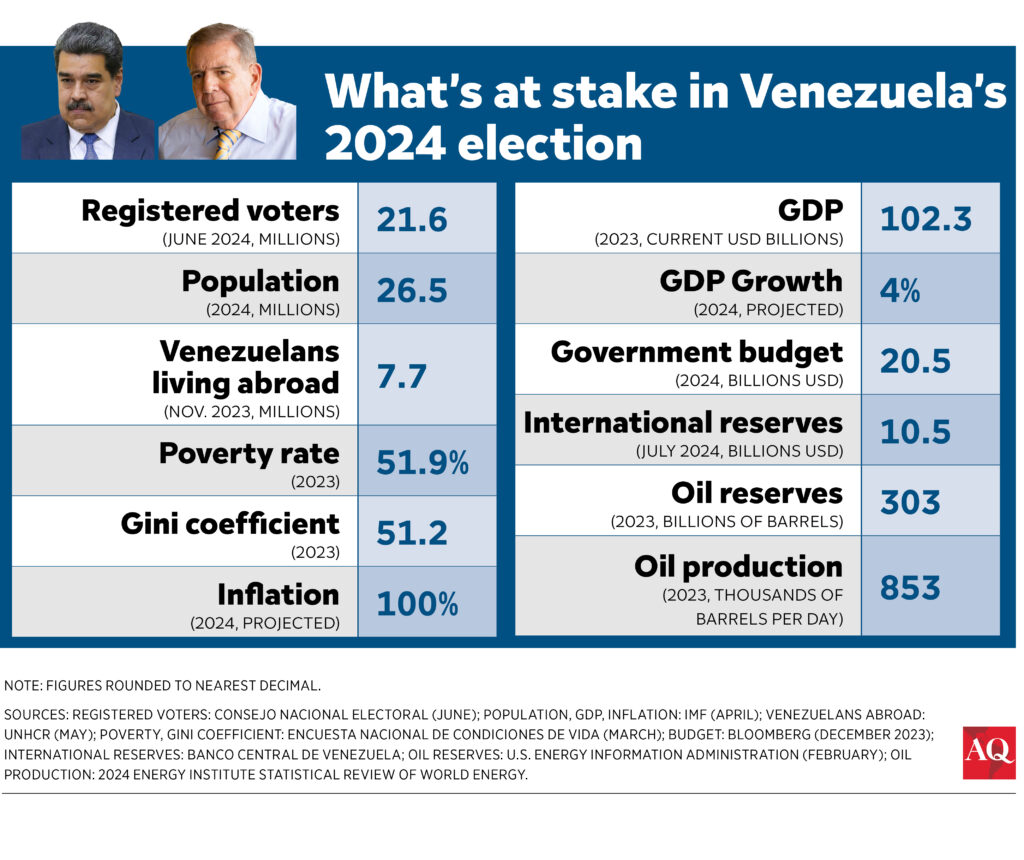

CARACAS — Venezuela’s elections on Sunday will be very different from the controversial votes of the last two decades. The country’s electoral playing field has changed so dramatically that Chavismo, the ruling political movement created by the late Hugo Chávez Frías, faces a real possibility of defeat at the ballot box for the first time in years.

Votes matter only if they are counted fairly, of course—a prospect that remains very much in doubt in a country where the government controls all levers of power, including the CNE electoral authority, which is tasked with overseeing election transparency and relaying results to the nation and the international community. Even so, fundamentals, including polling and on-the-ground campaign reporting, now favor the opposition so strongly that an irreversible victory is possible.

From 1998 to 2012, former President Hugo Chávez Frías easily won the four elections he ran in. After he died in 2013, Nicolás Maduro faced opposition leader Henrique Capriles Radonski the same year. That result was much different and confirmed what the polling showed: a close political contest. At the end of the day, Maduro was declared the winner. Then, in the 2018 election, the main opposition coalition—Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD)—opted to boycott, allowing Maduro to coast to victory. The Organization of the American States (OAS) called it “fraudulent,” and the U.S. labeled it as a “sham.”

Today’s landscape is different. Chavismo is enduring a low point in its popular support. Many of its proponents have been disillusioned by the Maduro government’s mistakes, the mismanagement of the economy, and the increasing isolation of a country that, in the recent past, was an integral part of the international community. Ahead of a generation’s most consequential presidential election, their vote is no longer assured.

A mobilized opposition

The opposition, meanwhile, has nurtured unity since its October primary and generated a great deal of momentum. After Maduro banned frontrunner María Corina Machado from participating in the election, the opposition unified around a little-known, soft-spoken, relatively non-ideological former diplomat: Edmundo González Urrutia. The result has been a heady, energized campaign led by Machado. It has attracted massive crowds even in small cities with events that have managed to get around the government’s intense media censorship through in-person campaigning.

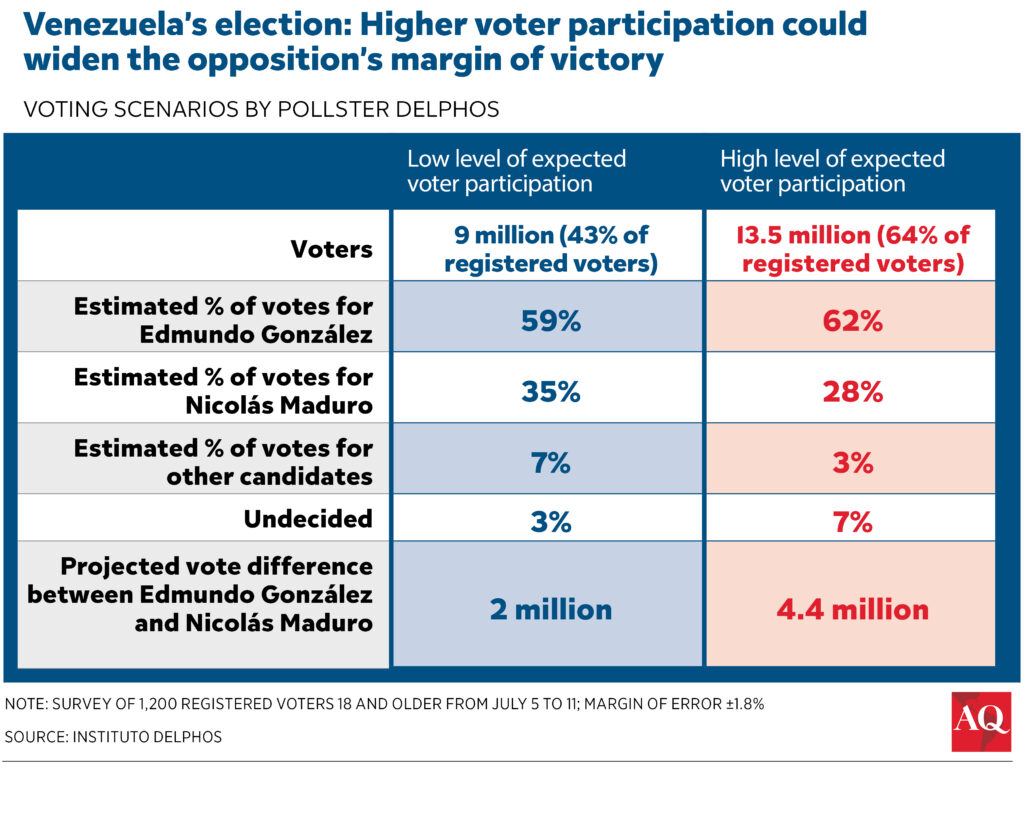

There also is polling to consider. The polarization of the electorate between the desire for continuity on the one hand and change on the other has been a constant since 2000. But now, the momentum for change seems overwhelming. Polling firm Delphos, where I serve as director, has tracked voter attitudes in Venezuela for over 20 years. Our data indicates that González Urrutia will win decisively. Delphos estimates that, in a low-turnout scenario of around 9 million total votes, the opposition will win 59% to 25%, or by about 2 million votes. In a high-turnout scenario of some 13.5 million total votes, Delphos sees the opposition winning 62% to 28%, or by about 4 million votes.

These results are consistent with those of all reputable polling companies in the country. Some companies are releasing polling showing Chavismo ahead, but they’re new outfits with no history and opaque backing that are all but certain to disappear just after the upcoming electoral contest.

Chavismo’s strategy

Finally, one of Chavismo’s favorite electoral strategies may not suffice this time around. In every recent election, the movement has attempted to “slice” votes away from the opposition little by little—a practice known locally as rebanado.

Given the opposition’s newfound popularity and momentum, it’s hard to imagine this strategy working. Even so, the government is trying. It has, for example, made it harder to register to vote, especially for the more than five million Venezuelans legally entitled to cast their ballot who have left the country due to its economic implosion. This alone shaved an advantage of at least 1 million votes from the opposition’s margin. (Even so, this is accounted for in our polling.)

The government has also tried to reduce turnout by abruptly changing voters’ polling places, banning the EU election observation mission and other international observers, and spreading the notion that an opposition victory would plunge the country into violence and chaos, among other actions.

But the weight of the opposition’s advantage, as measured in recent polling, seems too great to be overcome by these “slicing” maneuvers. The fundamental question is, what will those who have the ultimate responsibility for announcing Sunday’s results do when the big time comes around? All this adds up to two certainties: Tensions will be historically high on Sunday, and the outcome, for the first time in many years, is up in the air.