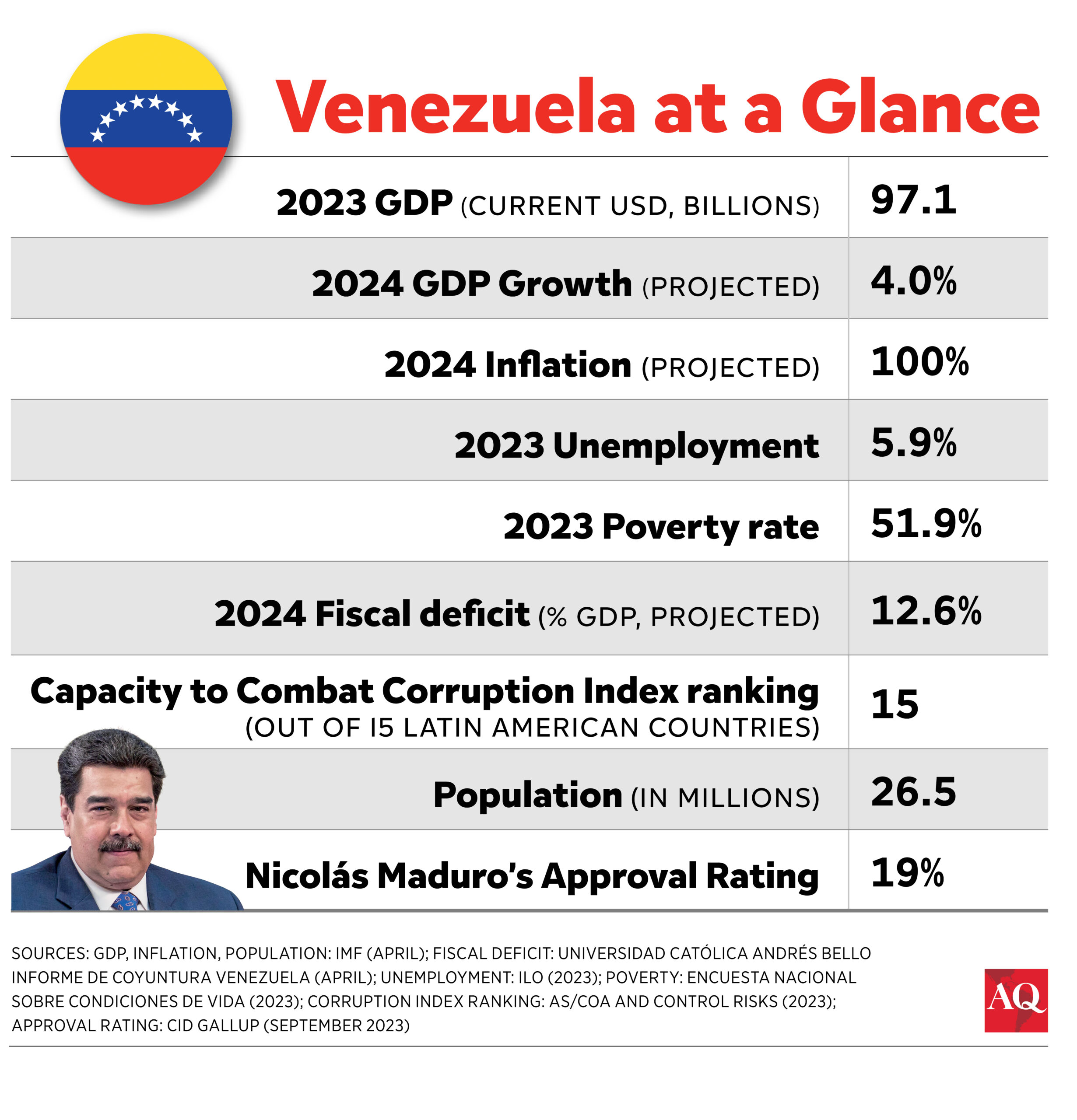

CARACAS— After eleven years of embattled rule at the hands of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela is set to hold, on July 28, its most consequential presidential election. The contest represents a unique opportunity for the country to enter a cycle of re-institutionalization and democratization. The vote may also usher the oil-rich nation into an era of economic recovery and stability that could see many citizens return.

Therefore, an electoral outcome that all political actors recognize as legitimate represents the only current constitutional path available to restore the rule of law, address the humanitarian crisis, and remove some of the international sanctions placed on the regime in recent years. In theory, a fair, transparent and competitive election could also help to boost economic growth—promoting the once-thriving private investment in the country, particularly in the oil sector—and finally strengthening its now-quasi-chaotic essential public services.

But in Venezuela, things are not as clear-cut because the political system has been designed so that the winner takes all. Without guarantees for whoever loses, the incentives to hold free and fair elections are currently close to nil. At best, the country will have a semi-competitive contest.

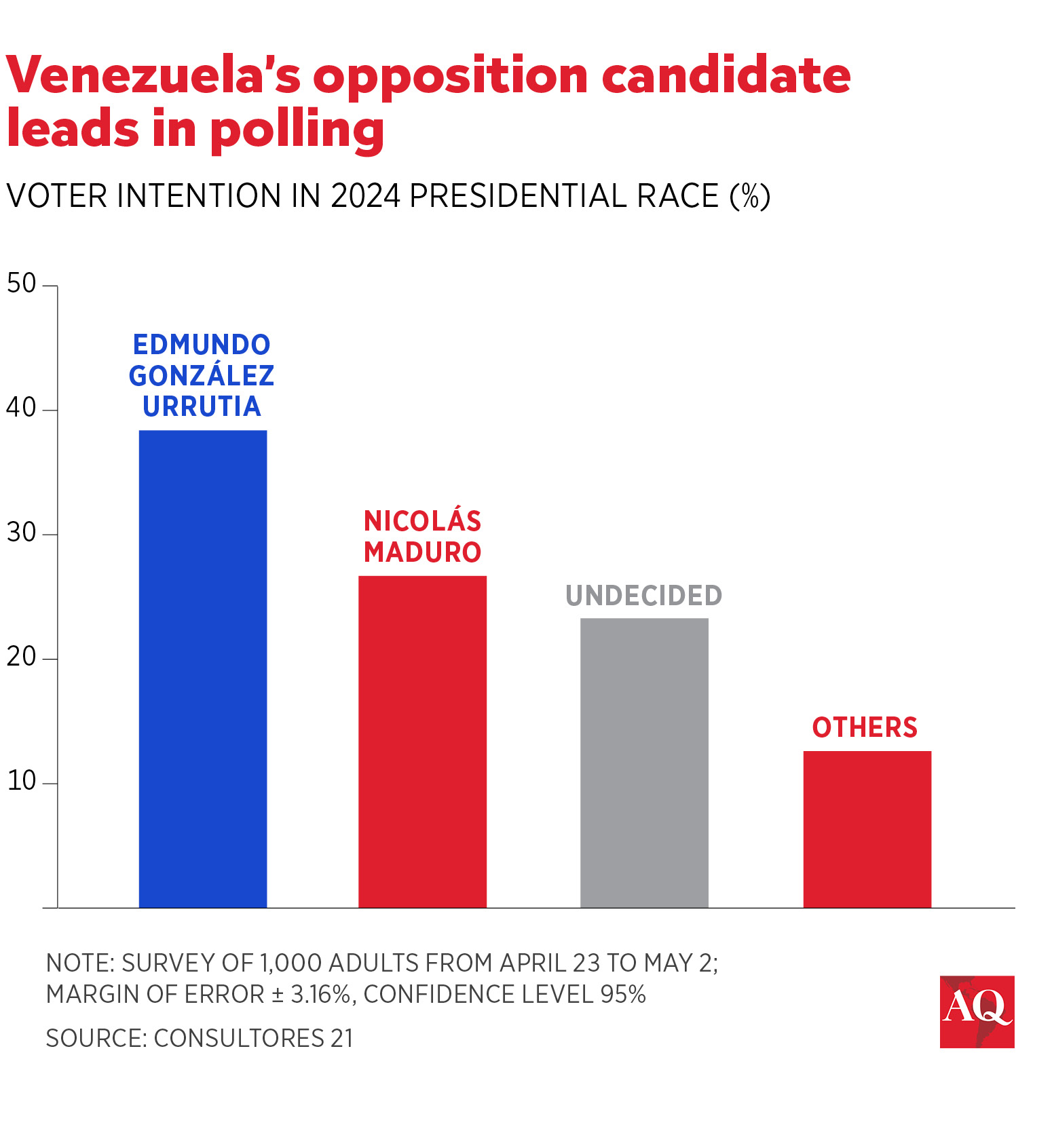

Most opinion polls show a vast majority of voters ready to punish Chavismo by voting in favor of the opposition, even if the leading contender, Edmundo González Urrutia, is an unknown retired 74-year-old diplomat who considers himself an accidental candidate. González Urrutia was unanimously anointed by a broad coalition of opposition parties only after several others were previously undemocratically vetoed from entering the ballot, including María Corina Machado, who won the primaries last October and is leading the campaign for him throughout the country.

As the electoral campaign unfolds, the political uncertainty for both groups is high, with neither knowing what will happen politically the day before and after the presidential vote. The opposition fears that at any point before the election, their candidate and its umbrella political party (MUD) can face a new ban or that the vote might suddenly be rescheduled. Chavismo, on the other hand, fears that a defeat at the polls can be translated into vicious political persecution.

As it stands, the presidential contest continues to reflect an existential conflict for both camps. Elections can only draw one winner and several losers. A defeat without a firmly previously negotiated settlement represents costs and risks that are not worth taking.

Unless these conditions change, any electoral results will be extremely fragile. They will also lack the legitimacy and the strength to promote a process of re-institutionalization and democratization. For Chavismo, losing the election with a large margin, as most opinion polls suggest, can allow the opposition to translate an electoral opening into a rapid political transition that some fear could be used, judicially, to punish them nationally and internationally for various crimes, among them, for human rights violations, illicit activities, and wide-spread corruption.

Fears ahead

The United States has already issued several public and sealed indictments related to these accusations. In early March, the International Criminal Court (ICC) authorized a full investigation into human rights violations in the country, and in April, Maduro agreed to allow the ICC to open an office in the country to proceed with their inquiries. This is a good step forward.

In addition, the U.S. has shown some willingness to review and potentially remove some of these indictments and personal sanctions. However, given the seriousness of these threats, Chavismo might be willing to use its strong grip over state institutions to limit, block, or postpone any political change.

By contrast, according to many pollsters, despite how unlikely this scenario seems today, if the opposition loses the presidential election, they could be completely wiped out from the political landscape. Chavismo holds control of a supermajority in the National Assembly, can directly influence the judiciary and the armed forces, and leads most of the country’s governors and municipal posts. Returning from exile would likely prove impossible for those opposition figures already facing politically motivated judicial actions in Venezuela. More than 270 political prisoners in the country are still waiting to be freed.

To worsen matters, Chavismo is convinced that if they manage to close the double-digit difference showing in these opinion polls by capitalizing on its clientelistic networks, as well as on its relative strength in rural areas, and stage a comeback to win the presidency, the opposition could decide to contest their victory or potentially claim fraud.

Venezuela’s political trap

Colombia’s President, Gustavo Petro, has emphasized the need to find a solution to this political trap. He has underscored the benefits Venezuela stands to gain from an initiative inspired by Colombia’s National Front Pact in the late 1950s, whereby both groups—the winners and losers—agreed on alternating in power.

Furthermore, Petro has highlighted as a potential model the most recent peace agreements with the FARC negotiated in Havana, which dealt with human rights violations through a complex judicial framework to address social grievances and restore individual rights.

Colombia’s president has correctly pointed out that Venezuela needs to have a difficult conversation on judicial and institutional guarantees that reduce the costs and the risks of losing power. Whether or not the Colombian case is a relevant reference is a different matter. Petro’s solution suggests a broader negotiated settlement between Chavismo and the opposition.

Political guarantees

Until now, the crumbling Mexico/Barbados talks mediated by Norway have focused on free and fair elections and lifting international sanctions against Venezuela. However, the country desperately needs to move in tandem to a more inclusive framework of judicial guarantees and institutional reforms.

Petro has also suggested the need to vote in a referendum on an initiative of this sort, perhaps along with the presidential election. This would pave the way for such a needed discussion once the country leaves behind the electoral campaign. To be sure, González Urrutia favors discussing amnesty after the vote, and Maduro talks about the need to bring peace once his third term has been secured. Privately, the initiative seems to have been welcomed by all relevant actors, but none want to publicly talk about it before the election, either because it makes them look too weak or not sufficiently strong.

However, not committing to a relevant agenda and setting some rules of engagement before the vote doesn’t make any of these promises credible. Petro’s warning seems well-grounded. The problem in Venezuela is that there is no consensus mechanism or public platform to allow political actors to discuss these issues and secure a peaceful, stable process of political change.

Without these mutual guarantees, the road towards re-institutionalization and democratization in Venezuela will, at worst, remain elusive. After more than 25 years, Chavismo and the opposition are still engaged in an existential conflict for power that will continue to be socially corrosive and politically destructive if judicial guarantees and deep institutional reforms are not introduced. Should the country prove itself incapable of overcoming this trap, the nation will fail to move forward. The July 28 presidential election represents an opportunity for political change, which most people want and should get.

Penfold is Global Fellow at the Wilson Center and professor at the Instituto de Estudios Superiores de Administración (IESA). He is the author of El País que se Muerde la Cola: Conflicto Político, Reinstitucionalización y Democratización en Venezuela (2023).

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify and other platforms