This was the week Nicolás Maduro stopped even pretending.

After months of stringing along his own citizens and the international community with hopes of a quasi-democratic thaw, Venezuela’s dictator arrested a well-known human rights activist and then abruptly kicked a United Nations’ human rights agency out of the country, giving its staff 72 hours to leave.

The tactics were old. But the feeling was somehow new.

Over the last five years, efforts to restore Venezuela’s democracy have come full circle: From the more than 50 nations who recognized Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president in 2019, to Guaidó’s failed attempt to rally the Venezuelan military to his side; to Donald Trump’s sanctions and unrealistic talk of a US invasion; to the more recent attempts at reconciliation; the lifting of some sanctions; and the agreement in Barbados last October to release political prisoners and stage some kind of presidential election later this year.

The feeling you hear now, from some activists in Venezuela and diplomats in capitals around the Americas, at least in private, is helplessness.

We’ve tried everything, carrots and sticks. And now we’re basically back where we started.

Which is to say: a narcostate that takes political prisoners, impoverishes its people, hemorrhages millions of migrants, and periodically pretends to be just reasonable enough to improve its international standing, and win some economic dividends, before slamming the door shut again.

There are whispers, as usual, that maybe we’re reading it wrong: That the forced disappearance of Rocío San Miguel, who has excellent contacts in the Venezuelan military, actually pointed to some kind of palace intrigue that left Maduro in a panic. That factions within Maduro’s regime continue to look for some kind of exit ramp, even after the January decision to break the Barbados deal by banning Maria Corina Machado as the opposition’s candidate.

“The regime is weak. It is cracking. They’ve run out of money. And most important of all, they’re conscious they’ve lost their social base,” Machado told a Center for Strategic and International Studies event this week. She said the arrest of San Miguel was designed to “paralyze” momentum among forces pushing for democracy.

Others had more prosaic explanations. “This is Maduro giving the world the finger,” David Smolansky, a prominent Venezuelan in exile, told me.

Either way, if Maduro has stopped pretending, then maybe the rest of the world should, too.

What does that mean? Well, somewhat uniquely among the world’s dictatorships, policy toward Venezuela in the United States, Europe and some Latin American countries continues to be treated as if democracy is just within reach – that if the world would only say the right thing, or find the correct mix of coercion and incentives, the door might come unlocked.

I personally wish that were true. But Venezuela, at this point, looks like a consolidated authoritarian regime, like Cuba (which advises Maduro and has been “going strong” for 65 years now) or Russia. In such cases, one should never lose hope for change – but it would come from the inside, abruptly, via a popular revolt or palace coup.

The international community can still do things to encourage the return of democracy. But it recognizes the sad truth that once a dictatorship takes hold, it becomes incredibly difficult to dislodge – and therefore focuses first on realistic options for managing the situation as it is.

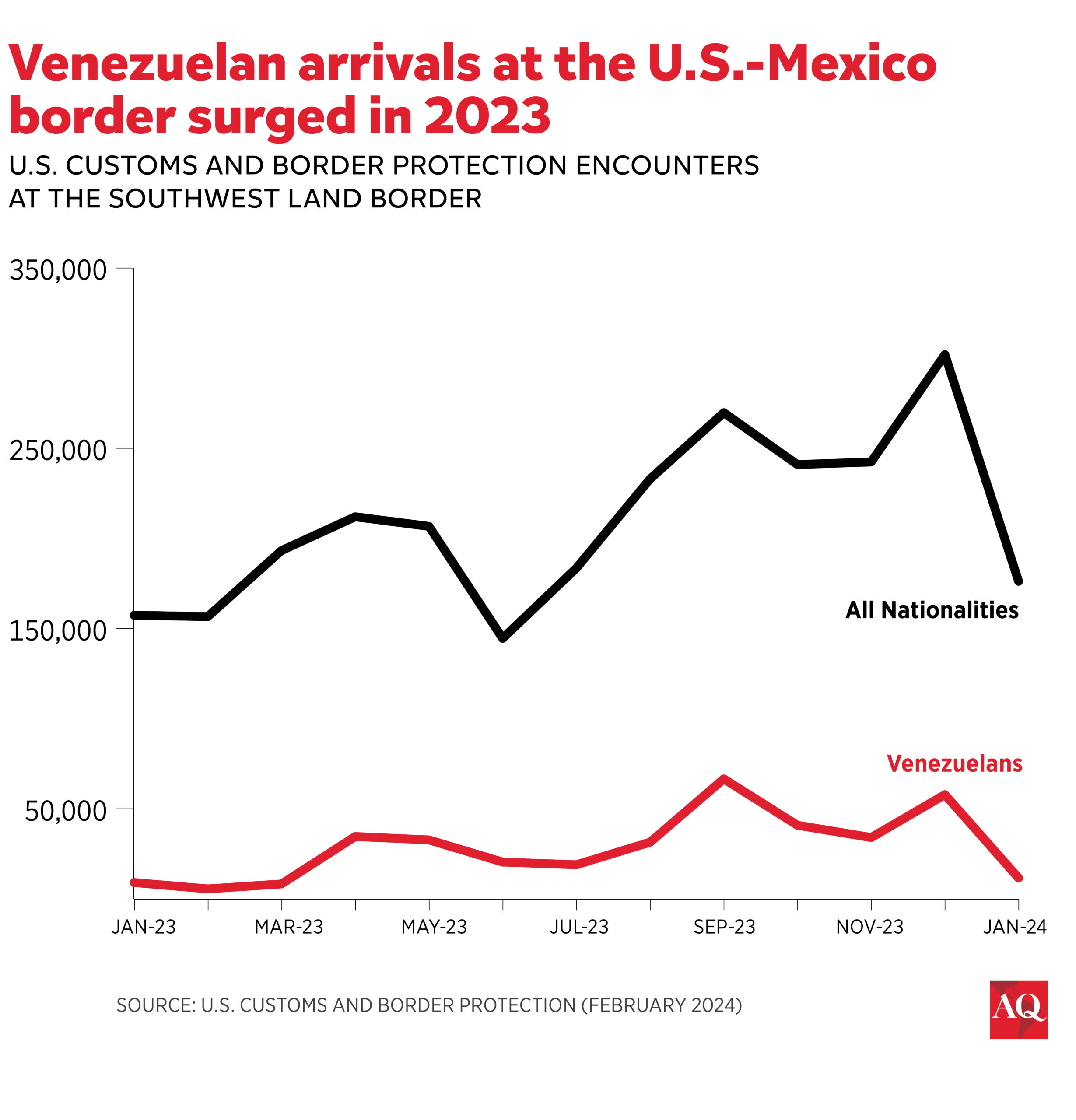

The Biden administration took a step or two down that road in 2023, when it eased the Trump-era sanctions on Venezuela’s oil sector and other areas. But U.S. officials continued to publicly link their decisions to progress on a democratic opening, apparently believing that they could “have it all” – a policy that would 1) Nudge Maduro out, or at least reduce oppression 2) Gain more access to Venezuelan oil amid the war in Ukraine and other global disruptions and 3) Improve economic conditions in Venezuela, which could in turn 4) Stem the truly massive, and growing, flow of desperate Venezuelan migrants coming to the United States in an election year.

That Goldilocks scenario is fully off the table now, after this week’s events. Pressure is coming from many quarters, including from some former presidents and political leaders from Latin America and Spain, to restore sanctions, and start up the punitive cycle once again.

The alternative would be to say: Unfortunately, Maduro has broken his end of the deal. Today we are announcing tough new sanctions on individuals within the regime, as well as new measures to support Venezuelans who continue to bravely push for democracy. But we believe that a full restoration of sanctions would further hand control of the world’s largest oil reserves to malign actors including China, Iran and Russia, both now and in the future. It would worsen the economic situation on the ground in Venezuela, sending another wave of migrants across the southwest U.S. border. And to be frank, we don’t think it would do anything meaningful to weaken Maduro’s grip on power.

That may be too politically toxic, especially during this election year.

The cost to U.S. credibility would be substantial, perhaps unacceptably so.

But if everyone were to truly stop pretending, it might be the most honest, and effective, approach.

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify and other platforms