SANTIAGO—In a country where the average life expectancy has increased from 67 to 80 years in just over a generation, maintaining a well-functioning pension system is not only critical but politically advisable. Even more so, considering Chile’s economy grows only 2% year-on-year, and by 2050, almost half of its population will be over 65 years old. How can the country confront this challenge?

In recent years, previous administrations have attempted to address the issue with limited success due to the ambitions of their proposals. Former Presidents Michelle Bachelet and Sebastián Piñera, from the center-left and center-right, tried in vain to pass wide-ranging pension reforms, and now President Gabriel Boric is on a similar journey with a bill that faces large obstacles in Congress.

Boric succeeded in getting the lower house of Congress to approve a new reform of the pension system in January, but lawmakers rejected the bill’s most important aspects. That meant that the Senate had to start practically from zero, and it has been analyzing the main aspects of the proposal since March. In an effort to speed up the discussion, the government fast-tracked the bill on June 13, as it hopes to reach an agreement before the municipal election campaign begins at the end of August. There’s agreement on an increase to the mandatory retirement contribution drawn from Chileans’ paychecks from 10% to 16%, but strong disagreement over what to do with the additional 6%.

The proposed law, first sent to Congress for discussion in November 2022, still looks unfeasible since it seeks an almost total overhaul of the nation’s pension system. The government insists that it won’t agree to a deal without more benefits for current retirees. But the opposition has remained inflexible, insisting that the entire contribution increase should go to workers’ individual savings accounts, mainstays of Chile’s highly privatized pension system. This is necessary due to the sharp drop in the national savings rate over the last decade and the enormous damage done by Covid-era decisions by Congress to allow citizens to take money out of their pensions. The withdrawals resulted in a $50 billion decrease in pension funds during the pandemic, more than a quarter of Chileans’ total savings.

What can be done? Given the current circumstances, the government should give up its attempt to pass a mega-reform and instead move forward in areas where there is consensus, to avoid repeating the failure of the two previous administrations on this issue.

There is a strong ideological component to this dilemma. For the left, any deal must entail a greater role for the state in the system, both in the use of pension contributions to finance pay-as-you-go or other benefits, as well as in the financial management of savings through the creation of a state pension fund (Chileans’ retirement accounts, called AFPs, are currently administered by private managers).

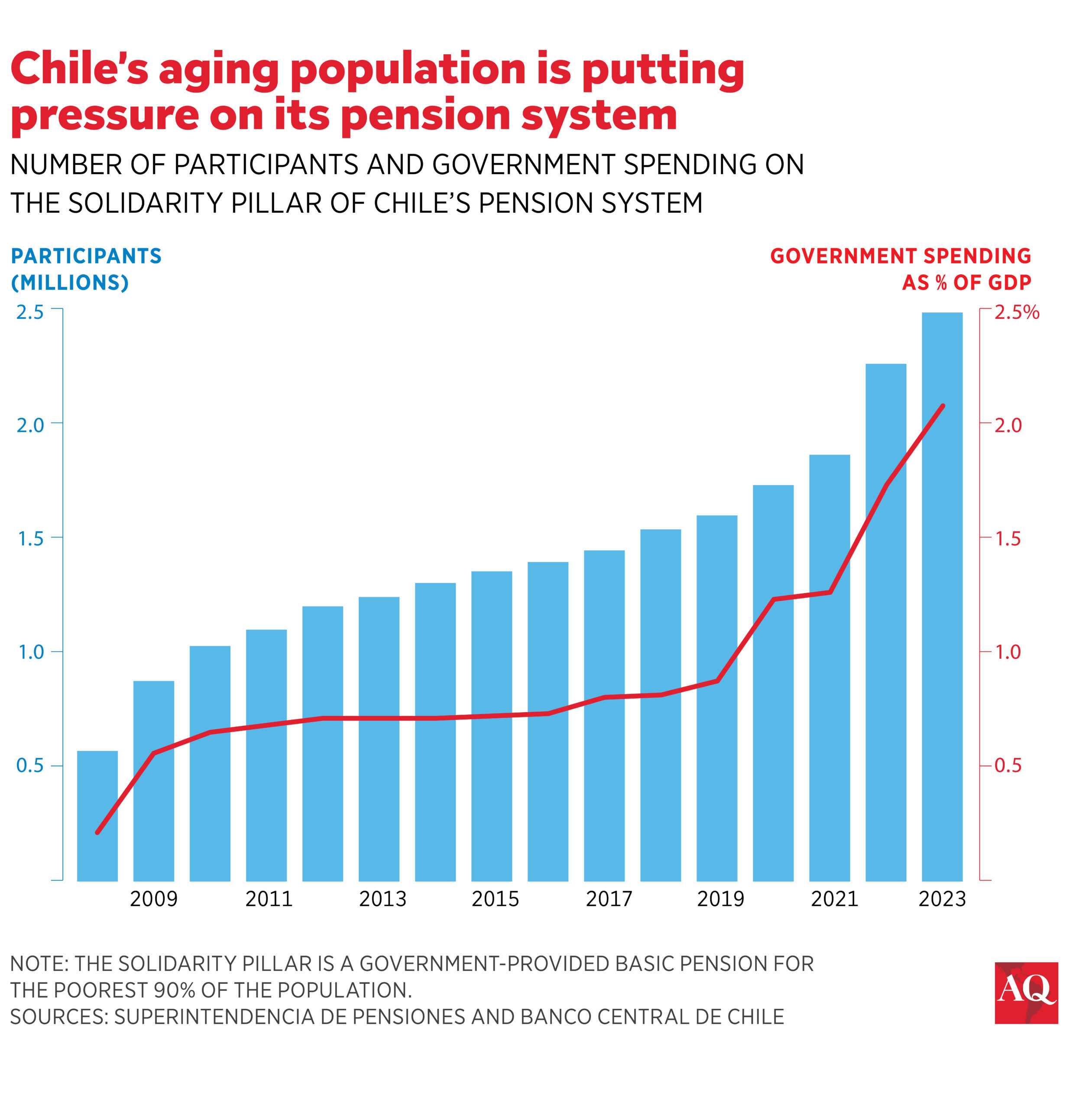

For the right wing, such a role for the state in the use and management of savings generates corruption risks as well as risks that resources may be managed with a view toward purposes other than generating long-term returns as a result of significant state participation in capital markets. Moreover, Chile’s aging population creates a serious problem: Currently, only 22% of Chileans are over 65 years old, a figure that will double in two decades. This means there is not enough time for the system, under the proposed reform, to generate the needed returns to cover the expanding number of retirees.

The proposal

The draft bill covers practically all aspects of pension policy. It raises the mandatory contribution rate from 10% to 16%, with a different management criterion for that additional 6%, which would go toward a state-run fund for current retirees, women, and lower-income contributors and toward financing a national policy for the care of people with disabilities.

Besides raising the mandatory contribution, the proposed legislation also separates the financial management of savings from the administrative processes supporting the system, handing over the latter to a state-awarded entity called the Autonomous Pension Administrator. It also changes the system for charging management fees and the bidding mechanism for members and modifies investment strategies. Finally, it raises the amount of the Universal Guaranteed Pension (the PGU, a state pension financed with taxes) established in 2021 and increases its coverage from 90% of retirees to 100%.

These are hard issues to find agreement on. However, there is consensus on raising the contribution rate, changing the funds’ investment strategies, introducing greater competition in the administration industry, and improving the PGU based on the amount of contributions.

The government should be open to making partial and gradual progress on these issues, incorporating aspects related to the two leading causes of low pensions: the retirement age and the high percentage of the economically active population that does not contribute, close to 40%. Neither problem is addressed in the government’s proposal.

High costs

Today, the country’s retirement ages are the same as they were in the last century: 65 for men and 60 for women. They date back to 1924, when the social security system was created, and life expectancy was well below those ages. Chile partially dealt with the demographic challenge by creating a private pension system in 1981—the world’s first—but it established a contribution rate of only 10%. Although that rate was feasible given the life expectancy of the 1980s, it has not been sustainable for some time now.

Faced with the difficulty of making progress on the reform, Minister of Labor and Social Welfare Jeannette Jara has insisted that retirees cannot continue to wait while the government is willing to compromise to reach an agreement. The minister forgot to mention that retirees’ situations have improved in the last five years: The amount of state resources has tripled, so the replacement rates of low-income retirees are well over 100%. Of course, the fiscal cost of this benefit is very high, and if the economy continues to grow by only 2% year-on-year, its future financing looks uncertain.

Opting for a more gradual pension reform would be advisable. This is how our social security system has been refined in recent decades and the path adopted by Mexico, Brazil, Australia, and Spain, among others. Gradual progress could also improve the dysfunctional political climate of the last decade. Decision-makers should have the necessary will to modernize the Chilean pension system: Its gradual transformation is feasible and imperative.