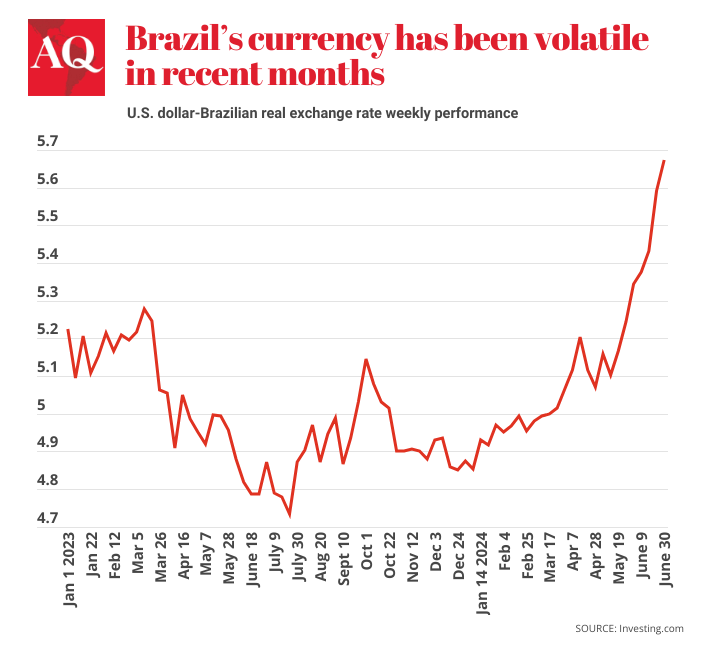

A year-to-date chart of emerging markets’ currencies shows that the weakest performance has come from the Brazilian real. While the Mexican peso gyrated in the days after the election of Claudia Sheinbaum in early June, and other emerging market currencies such as the South African rand and Indian rupee wobbled after their own elections, it is the Brazilian currency that has performed the worst, now down 7% in just the last month. How concerned should President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—and investors—really be?

As has often happened throughout Brazilian history, fiscal worries are at the forefront, with markets demanding some adjustments to spending policies. The “fiscal framework” introduced by the Lula government just a year ago appears fragile, lacking credibility and fraught with the risk of revisions. Caught in the middle of this volatility is Brazil’s Central Bank (BCB), which faces the challenges of rising inflation expectations, which are above the 3% target, market worries over the fiscal deficit that surpasses 9% of GDP on a nominal basis, and the aforementioned weakening currency. With the headline interest rate at 10.50%, and the BCB having recently “interrupted” its sequence of cuts, markets are pricing in hikes over the remainder of 2024 and 2025. Tough policy decisions lie ahead.

There are several important issues that make monetary policy in Brazil extremely complicated.

First, the inflation target in Brazil is now 3%, having been lowered from 4.5% in a gradual fashion over the last several years, to a level consistent with the inflation target in other Latin American countries such as Chile, Colombia and Mexico. However, this represents an ambitious target, given the high degree of indexation in the Brazilian economy, the expansionist state of fiscal policy in the years since COVID, and the country’s own turbulent history with inflation. Over the last decade, IPCA inflation, the main indicator used by economists, has averaged a shade under 6%.

Second, the fiscal policy of the current Lula government is expansionary, which complicates life for the BCB. The most recent data shows primary expenditures growing at a double-digit rate. Third, global interest rate markets have been turbulent with markets pushing back their expectation for when the Federal Reserve will initiate rate cuts. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is the issue of the BCB transition. BCB President Roberto Campos Neto’s term ends at the conclusion of 2024, and President Lula will make the decision regarding his replacement. The parlor game of who will replace Campos Neto has taken on a life of its own in recent weeks, with various “sources” proclaiming that a certain economist is—or is not—gaining or losing favor in the process to head the BCB. Many analysts believe that Lula will choose someone apt to conduct monetary policy in a more accommodative way than has been the case under Campos Neto; current BCB Board member Gabriel Galípolo is the name garnering the most attention for the position. Formerly Deputy Finance Minister during the first months of the Lula administration, Galípolo also advised Lula’s own Presidential campaign on economic issues.

How should the BCB react to this environment? It will need to retain a restrictive policy stance for the foreseeable future, and in its recent communications it has stated this intention. The most recent BCB survey of market economists shows that inflation expectations for 2025 stand at 3.87%, having risen around 35 basis points since April, when fiscal targets for 2025-2026 were loosened. Should the survey median for 2025 rise above 4%, the BCB may have no choice but to hike. “Reanchoring” expectations for inflation, or at least preventing further deterioration of expectations, are vital in a country with a history of volatile prices.

In terms of the currency, there have been growing mentions of the need to intervene, as a means of stabilizing the real. However, at this juncture, intervening in the FX may be counterproductive. The main reason for currency weakness relates to the aforementioned fiscal problems and questions around BCB transition; intervening in the FX resolves neither question. To stabilize the real requires the Lula government making some tough decisions about expenditures. The Brazilian budget is notoriously inflexible and the idea of delinking certain benefits from the minimum wage appears anathema to Lula. The math behind the current fiscal framework however does not suggest that its targets can be met without some real adjustment. The political class will need to make unpopular decisions in this area.

Meanwhile, efforts must be made to minimize the impression that the BCB could be vulnerable to political pressures. The vote at the May meeting, where the four recent Lula appointees to the board supported a larger rate cut, created an impression that the post-Campos Neto led BCB could be more dovish. Inflation expectations rose as a result, and rates markets panicked. However, importantly for market participants, the June meeting showed unanimity. The 9-0 vote to hold the policy rate steady showed that the Lula appointees were also on board with the importance of trying to anchor inflation expectations. Galípolo has been consistent of late in stating the importance of convergence to the 3% target and maintaining a tight policy stance. It is important that the various members of the BCB Board deliver this message, to remove any doubt that political pressures or Lula’s criticisms will weigh on policy decisions.

By early 2025, Lula appointees will control the majority of the BCB board. Political interference in a Central Bank’s reaction function only serves to increase inflation expectations and affects the credibility of the institution, a lesson many countries have learned over the years. BCB’s long sought independence, which was validated by the Congress in 2021, remains intact however. Restrictive monetary policy is never popular, but as other central banks in the region continue with their easing cycles (including Chile, Peru, Colombia, and with Mexico likely to resume cuts later in the year), it will be worth watching whether the BCB bolsters its credibility through the transition process by taking a hard stance.

—

Rosen is a strategist and economist for Latin America with Emso, an emerging markets-focused asset manager. He has also worked at Goldman Sachs, Trust Company of the West, and Itau Asset Management.