This article is part of AQ’s special report on Latin American mayors.

SANTIAGO – Early on a winter morning in 1999, 1,650 families surged onto a 60-acre plot of privately owned land in the Santiago district of Peñalolén, completing the first illegal land occupation since Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

The encampment soon swelled to become one of Chile’s largest. Carolina Leitao has spent part of her career in politics dealing with the fallout – first as a city council member who helped relocate the families to formal housing over a period of several years. More recently, as Peñalolén’s mayor, she has helped transform the area into a lake, several soccer pitches, a skate park, a recycling facility and a velodrome that was used for the 2014 South American Games. (The owner of the land was eventually compensated by the government.)

The pragmatic, humane solution to a thorny problem was typical of the approach that enabled Leitao, now 42, to be elected to a third consecutive term in May despite the massive anti-incumbent feeling sweeping Chile.

It may also help point a way forward as the country writes a new constitution that seeks to address glaring inequalities in housing and other areas. “Occupying terrain cannot be the easiest way of getting housing in Chile,” Leitao told AQ.

Born in Santiago, Leitao spent part of her childhood in the southern city of Chillán before returning to the capital when she was five years old, going on to study law at the University of Chile. At 18, she joined the Christian Democrat Party after having volunteered in its youth wing, and later became the party’s vice president. When she became mayor, she promised to focus on the district’s inequality and environmental challenges while encouraging residents’ active participation in decision-making.

However, her second term was dominated by the pandemic and Chile’s era-defining social movement.

“I have been critical of the national government’s pandemic strategy, which has disproportionately affected the poorest people, and local leaders have had very few opportunities to participate and give our opinion,” Leitao said.

The pandemic exposed disparities in Peñalolén, such as yawning differences between connectivity and resources across the district. Leitao’s team responded by distributing nearly 7,000 SIM cards to get students online during lockdown, and by funding tablet computers for kids learning to read.

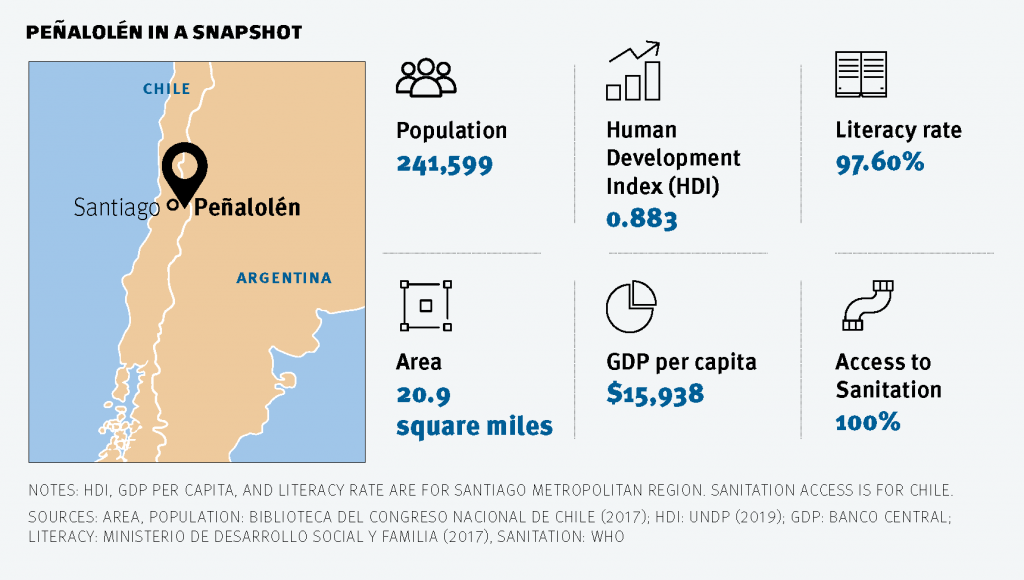

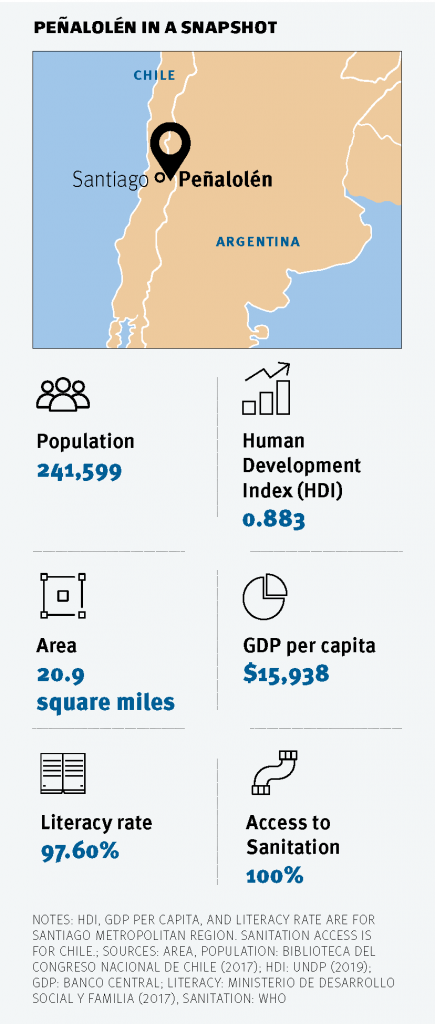

Despite the challenges, Leitao sees her district of some 260,000 as a “mini-Chile” that can be a laboratory for rethinking how government can work. Founded on the footprint of several large estancias in 1984, Peñalolén’s 21 square miles sit between Santiago’s wealthy northeastern districts and the working-class peripheries to the south, stretching from the crowded valley floor up into the foothills of the Andes.

Leitao is critical of the ways she sees power and privilege as unequally distributed, and she has delegated some decision-making to local groups – historically uncommon in Chilean politics.

“The social movement and pandemic have made leadership in the municipalities more visible, as (local leaders) are the ones who hear about people’s experiences,” said Leitao. She has expanded neighborhood discussion groups that were set up in 2006 to convene grassroots leaders to discuss local priorities. During her government, the groups have grown to 48 from their initial 18 – and she plans to visit each over the course of her term.

Leitao is also building on the district’s history of participatory budgeting, which is carried out every four years. The projects that receive the most votes are implemented, provided they pass a threshold of 5% participation among residents over 16.

In 2019, some $750,000 (533 million pesos), equating to 0.9% of the municipality’s budget, was designated for 10 projects across Peñalolén, which included revamped soccer pitches, street lighting improvements and a new skate park. The pandemic has inhibited the developments, but Leitao has pledged to expand the pot for participatory budgeting in the future.

Another axis of Leitao’s management in Peñalolén is environmental protection and mitigating the effects of climate change – to which the district is particularly vulnerable. In 1993, a devastating landslide killed 26 people and damaged more than 5,000 homes, a reminder of the risks of heavy rainfall in the community.

Leitao’s team won a regional prize for its environmental plan, which encompasses energy and water efficiency, waste management and environmental education. The municipality has also pioneered a recycling scheme that trained and equipped informal garbage collectors. Several municipalities elsewhere in Chile have adopted similar schemes.

Today, Chilean politics is undergoing its own metamorphosis, with decisions being made that will shape the country for decades to come. Leitao, for her part, is staying focused on the changes she can make in the short term.

“My focus today and for the next four years is on transforming Peñalolén into a more welcoming, fairer and safer municipality.”

__

Bartlett is a freelance journalist based in Chile. Follow him on Twitter at @jwbartlett92