METETÍ, Panama —The late ex-president of Peru, Alan García, once quipped that Latin America’s cocaine cartels were the region’s “only successful multinational.” Now, there’s another: the transnational migration economy, made up of human smugglers and legal businesses that ferry migrants desperate for safety and economic opportunity through difficult-to-cross national borders between South America and the United States.

No part of the trans-continental journey is easy. But at bottlenecks where the going gets especially tough—either due to natural obstacles, like Panama’s dense and roadless Darién Gap jungle, or because of increased policing at the Guatemala-Mexico or U.S.-Mexico borders—the profits are huge. And high-profit bottlenecks have only multiplied as countries including Mexico, under pressure from the United States, have taken steps to make it harder to move north.

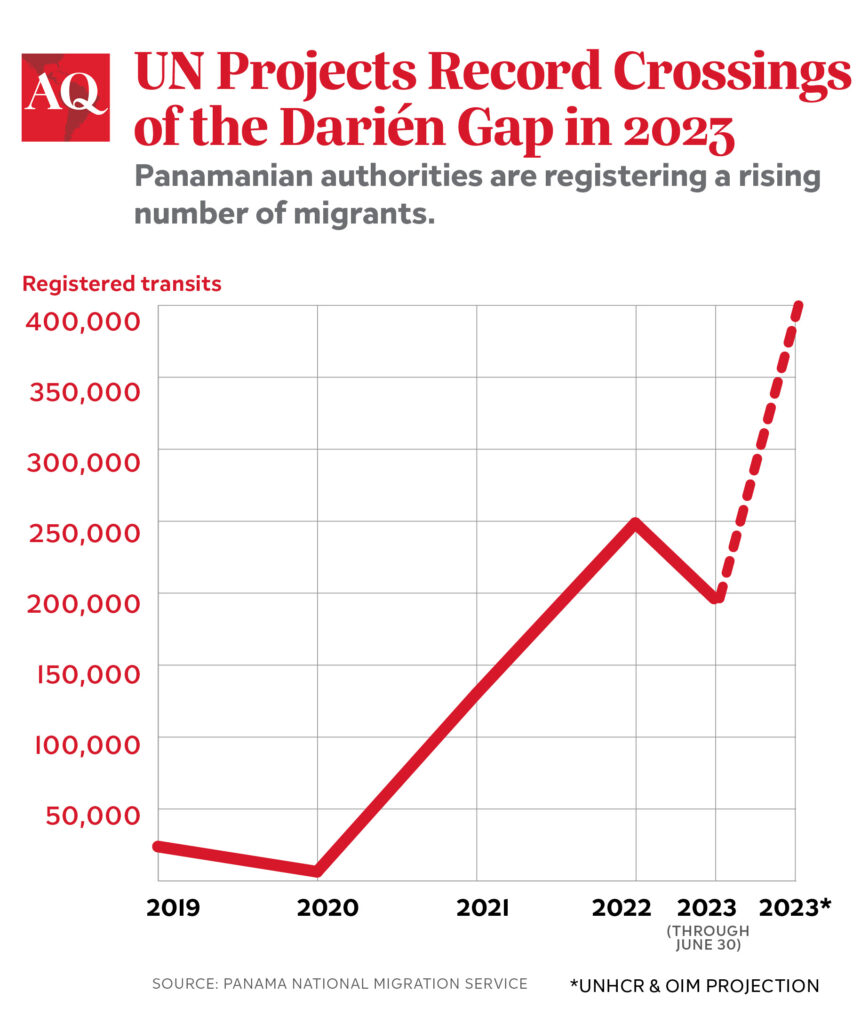

Now, the associated bonanza is enriching legal businesses and organized crime groups alike—often under the watch of complicit, or at least complacent, state authorities. With no signs of mass migration abating—400,000 people are expected to cross the Darién region this year—the new boom economy and its pernicious side effects are likely here to stay.

Underground bonanza

By the time I met Francisco, a Venezuelan in his late teens, at the government-run Lajas Blancas migrant reception center on the fringes of Panama’s Darién National Park, he was out of cash.

Like many of the 183,000 migrants who have taken the same overland route already this year, Francisco purchased a boat ticket to cross the Gulf of Urabá, and then paid a hefty sum to a local guide in Colombia to lead him to the Panamanian border. Prices vary depending on the length and safety of overland routes through the Darién. Insight Crime reported prices ranging from $70 to $150 in November of last year. Francisco, crossing in June 2023, paid an even higher fee, which seems to be the new normal. The Clan del Golfo, Colombia’s largest criminal syndicate, requires migrants to travel with such guides, taxes the profits, and enforces rules against robbing and assaulting migrants to avoid shrinking the pool of customers.

The Panamanian side of the border—bereft of state authorities or a single dominant criminal group—is more anarchic, and soon Francisco hit another all-too-common setback: He was robbed by armed criminals, who took almost everything he had, including his shoes. After making it to Bajo Chiquito, an Indigenous community of about 300 inhabitants, in beat-up flip flops he found along the way, Francisco used his last $25 to buy a seat onboard one of the communities’ canoes—a ferry service that is the only way out of the jungle. Based on the going price of tickets, and the hundreds of migrants that use the service each day, the ferry business could rake in hundreds of thousands of dollars each month. Migrants without enough cash have been subject to forced labor or have had to trade their cell phones to leave town, International Crisis Group researcher Bram Ebus told AQ.

But predatory profit-making doesn’t stop at the Darién’s outer limits. It continues in Lajas Blancas reception center, just outside the jungle—one of two such sites where migrants are required to wait by camouflage-clad police from Panama’s National Border Service (Senafront) until they can afford a $40 bus ticket, or land one of a few coveted free seats, on a shuttle to the border with Costa Rica. By the side of the bus stop, there is a short wooden building with a Western Union sign. In fact, there is nothing official about the shop: It is run by locals who act as intermediaries and require migrants’ relatives to wire money to their own Western Union accounts before passing on the cash—with a sizable chunk taken out. Because migrants are barred from leaving camp, it’s their own way to access funds. The same fraudulent set-up has been spotted elsewhere along the route out of the Darién.

Francisco, without family who could wire him money, sold snacks for local vendors within the camp for a dollar or two a day. But he found himself perpetually short on the cash he would need for a bus ticket, as he struggled to feed himself off the camp rations alone. The Panamanian government does not directly contract the bus companies or set prices, but it does decide which companies can enter. This resulted in a scandal earlier this year when an out-of-repair bus headed toward the Costa Rica border crashed, killing 44 of those onboard. In July, a transport workers’ union leader denounced the state’s Authority of Land Transit and Transport for allowing only one company to operate, allegedly generating up to $8 million in profits to date in 2023.

The money trail with a dead end

Past attempts to “follow the money” in and around the Darién region have hit dead ends. Panamanian government officials and international NGO workers I interviewed pointed to new cinderblock houses and increasing drug and alcohol use in local communities as proof of where the money ended up, and it’s true those developments reflect big material changes for communities that have long ranked among Panama’s poorest. Still, poverty remains widespread. It’s difficult to fathom that all—or even most—of the profits stay local.

Given the limited state presence in the Darién, it’s not surprising that public officials say they don’t know where all the money ends up. Senafront and the Ministry of Security are virtually the only state agencies with a footprint in the area. The Attorney General’s Office has just one prosecutor dispatched to the area: a post it fills on a rotating basis every few weeks. The government, like most others throughout the hemisphere, is focused on making the movement of migrants through its territory quick and invisible to its own citizens. Following the money could disrupt the businesses that ferry migrants along. It’s likely that the migration economy is already creating incentives to keep it just the way it is—extortionary for migrants, but profitable for those they encounter along the way.

Meanwhile, although some locals appear to reap huge profits, the long-term prospects for their communities are grim: children have been pulled out of school to help parents run migration-related businesses and agriculture is in decline. La Peñita—a Panamanian village that once received many migrants, but now receives few—recently asked authorities to redirect migrants back through the community.

The predatory migration bonanza isn’t limited to the Darién, of course. It’s booming as far away as Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, where guides charge migrants hundreds of dollars to cross the border. So, too, is conflict, as cartels battle for control of the lucrative trade.

Ultimately, the restrictive immigration policies of the United States are the root cause of Latin America’s new, predatory multinational business. If safe, legal pathways were abundant enough, no one would feel compelled to travel the Darién or other dangerous routes that make the business of controlling migration so profitable. Until quick, safe and legal pathways for immigration undergo a major expansion, the new boom economy and its unscrupulous operators will continue to thrive.