LIMA — President Dina Boluarte will soon mark six months in office, overcoming an initial period of great social upheaval. Today Peru is in a relative state of calm, but the specter of political instability remains. The government is weak and unpopular—its polling sits at a mere 25% approval rate—and, apart from economic recovery measures, it lacks a coherent and comprehensive policy agenda. Addressing this latter point has become increasingly urgent, as poverty rates have climbed over the past year.

The government aims to develop an agenda to enhance its social and political legitimacy as it faces intense scrutiny from the international community following the release of a recent report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The report’s findings include multiple instances of excessive force and repression employed by security forces to quell political violence in the initial weeks of the administration. The attorney general’s office investigation into the alleged abuses is ongoing, and any violations of the law should rightly be pursued. However, any analysis of this situation demands a balanced view, free from the constraints of political and ideological bias.

Peru saw former President Pedro Castillo attempt to remain in power through a failed coup, which precipitated an escalation of violence unseen for 30 years. Echoes of bygone political violence have spurred most Peruvians to whittle their demands down to sociopolitical stability. These demands will, however, remain unmet if politicians continue to undermine democratic institutions and subjugate their constituents’ desires to their own.

Although there are no formal alliances, there is a symbiotic relationship between Congress and the executive. Both aim to remain in power through 2026. Attempts at making early elections constitutionally viable have been sabotaged by incumbents intent on remaining in power within their respective branches of government. Moreover, right-wing and right-of-center parties in Congress have actively kept the current government afloat.

However, political stability remains frail. Congress is polling lower than the executive as it continues to promote self-serving legislation. Worse yet, radical factions at opposite ends of the ideological spectrum are entering into political pacts, fixated on securing appointments to crucial institutions, such as the Ombudsman’s Office and the Constitutional Court. Citizen priorities such as fighting corruption, crime and violence remain largely unattended by public authorities that remain deeply mistrusted.

In this context, it is worth addressing whether economic recovery will be undone by a prolonged political crisis beset by disenfranchised citizens. The economy posted practically zero growth in the first quarter. This slowdown is the result of the negative impact of social upheaval, especially in southern Peru, which was followed by torrential rains and flooding in the north caused by abnormal cyclonic activity. Worse still, the risk of an El Niño of significant magnitude restrains the economic outlook.

Even with these contingencies, pessimism seems to be giving way thanks to reduced uncertainty associated with early elections. A political truce and the reduced likelihood that disruptive statist policies will be pursued (via a Constitutional Assembly) have improved investor confidence. However, GDP growth forecasts for the remainder of the year remain around 2%, below official estimates and insufficient to improve the well-being of most Peruvians. Faster growth is critical in light of the deterioration of social indicators.

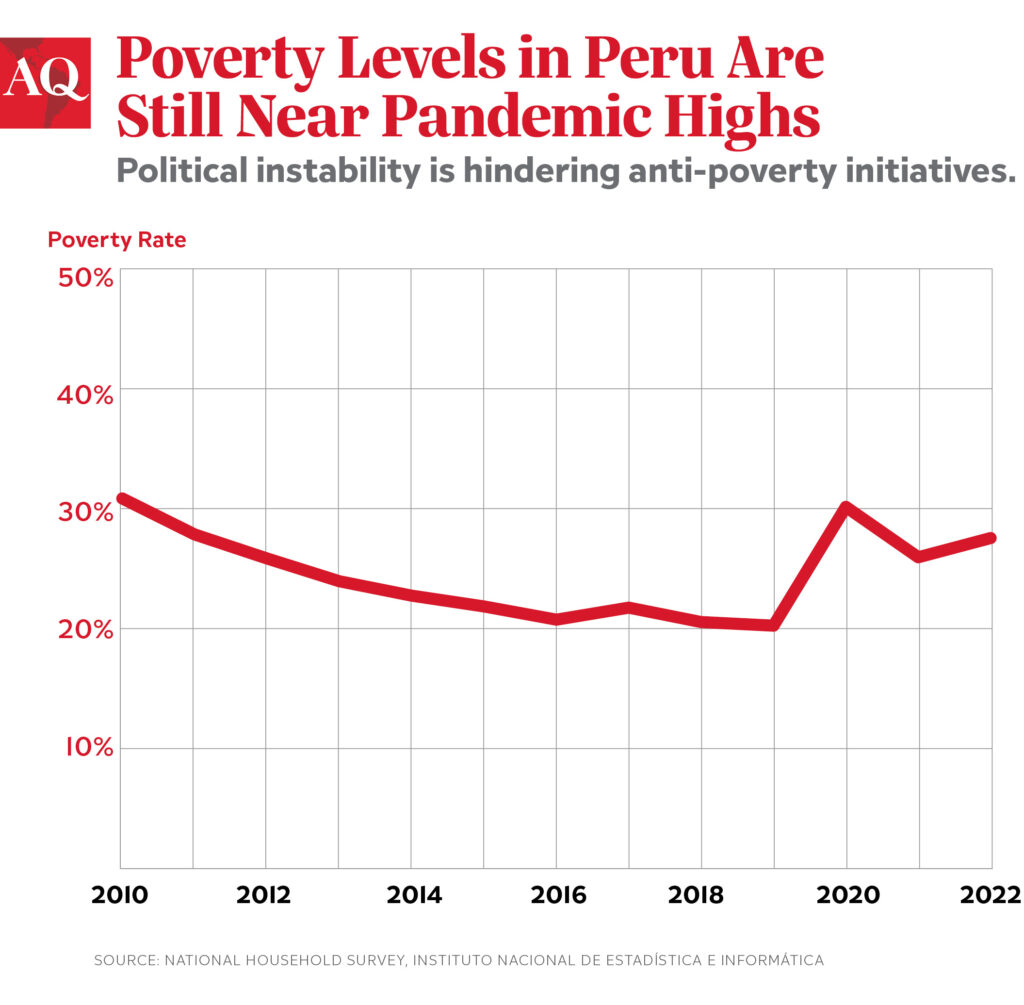

The poverty rate increased from 25.9% in 2021 to 27.5% in 2022, way above the rate posted before the pandemic. This corresponds to higher food prices, which particularly affect the poorest, and a sluggish economy. The urban poverty rate has spiked, having grown by 10 percentage points from 14.6% in 2019 to 24.1% in 2022. This amounts to an additional three million urban poor, many of whom participate in the informal economy as independent workers and migrants. The government is ill-prepared to undertake policies to support the urban poor, who unlike the rural poor do not benefit from targeted cash transfer programs. Therein lies the policy challenge in extending social safety nets that are financially sustainable (including pension reform). Still, the main priority is restoring higher economic growth rates and accelerating job creation. It is worth recalling that during the past three decades, sustained GDP growth accounted for over 80% of poverty reduction in Peru as the poverty rate fell from 60% in 1990 to 20% in 2019. This represented one of the largest poverty reductions in Latin American history.

It is essential that Peru resume vigorous economic activity in an environment in which commodity prices remain elevated, especially copper prices boosted by energy transition prospects. However, this goal is virtually unattainable considering the absence of new major mining projects. The persistence of high costs, unjustified delays in the approval of social and environmental permits, and the reluctance of some new regional and local authorities to support projects for fear of rejection by certain anti-extractive movements lower Peru’s competitiveness. If business confidence consolidates, private investment in non-mining sectors could recover, especially in public infrastructure sectors prioritized by the government. But so far, the investment growth outlook remains bleak. Expansionary fiscal policies, particularly in public works, are not sufficiently compensating for lower private investment.

Private consumption, in turn, will continue to support growth, but with less dynamism. The informal sector and the lower socio-economic segments will drive private consumer spending growth as their labor income purchasing capacity improves. This improvement will come as higher interest rates consistent with the Central Bank’s restrictive monetary policy reduce inflationary pressures.

Even with the maelstrom of political crises that have occurred, strong macroeconomic fundamentals remain, as evidenced by an appreciated sol regarded as a “strong currency” demanded by Peru’s neighbors. Open market policies, a constitutional framework that supports a market economy, and an entrepreneurial labor force and business community also contribute to make Peru’s economy resilient. Still, the main challenge continues to be building more robust, accountable and stronger institutions. Fixing the broken political system is an urgent task that elites need to pursue. Otherwise, recurrent political crises will seriously impair Peru’s social and economic progress and economic resilience will be a memory from the past.

—

Castilla is an economist. He served as finance minister (2011-14) under President Ollanta Humala and as Peru’s ambassador to the U.S.