The Past, Present and Future of Soy in South America

Over the past five decades, the continent has become a soy-growing behemoth. But is the boom over?

BY NICK BURNS | OCTOBER 2, 2024

PHOTOGRAPHY BY NICK BURNS

This article is adapted from AQ’s upcoming special report on food security in Latin America.

BAIXA GRANDE DO RIBEIRO, Brazil—Here, in a small brick building, a three-hour drive down muddy roads and across a river barge from the nearest city, one possible future for soy in South America is on display.

Agronomists watch on computer screens as little icons creep across a map—showing harvester machines threshing soybeans across the farm’s enormous span, 60 miles from end to end. The display shows weather forecasts and conditions in the fields, fed live over a 4G connection by a network of solar-powered monitoring posts.

The technology isn’t here just to impress visitors from abroad. This year, it helped the team at Fazenda Ipê overcome an El Niño-linked drought that took a hit on the area’s yields. Based on analysis of 10 years’ worth of data, the decision-making team opted to plant on a delayed timeline, to take advantage of a likely second planting window later on. The result was a harvest that ended up even with last year’s totals, despite far worse conditions.

“The growth we’ve had in recent years doesn’t come from nowhere,” said Gilmar Cadore, director of Insolo, the company that owns Fazenda Ipê. “We’re using more technology, we’re getting a better scientific understanding, and it’s because of that that Brazil’s become the world’s biggest soy exporter.”

Not every farm in the region is so high-tech. But make no mistake: Soy is big business in South America, which now produces more than half of the planet’s supply following 50 years of extraordinary growth—a truly epic story that involves technological innovation, both the helping hand and the hindrance of government, and the rise of middle classes half a world away.

The question facing the industry today is whether those days of heady expansion are over.

Soy is big business in South America, which now produces more than half of the planet’s supply.

Producers like Ricardo Faria, who owns Insolo and is one of the country’s most prominent farmers, argue that good times are still ahead. Emphasis will go from cultivating new land to getting more productivity out of land already under cultivation, they argue, while soy will remain a mainstay of food security in a growing world, and new markets will come from biofuels and up-and-coming regions like southeast Asia.

“In the past, soy was a product for pigs and chickens—today, it’s clean energy for the world,” said Faria.

But others say the soy business faces a forbidding set of challenges, as China’s growth slows, risking a glut in soy markets, as production continues to rise. Many fast-growing countries don’t eat much red meat—a crucial determinant of demand for soy. Soy’s role in the deforestation of South America’s tropical savannas has come under increasing scrutiny from the European Union and others, while the crop is also a particularly heavy user of pesticides and other chemicals.

Here in northeast Brazil, some 600 miles from Brasília, both the promise and limitations are clear. Half a century ago, this region was mostly given over to small-scale cultivation of crops like indigo and cotton, and many locals migrated to the southeast to escape hunger and find work. Today, in booming Balsas, the nearest city to the farm, billboards advertise agribusiness services and jewelry stores cater to a new upper-middle class, some of whom moved here from the prosperous south or from older soy boomtowns in the center-west.

Soybeans are now the single biggest export for both Brazil and neighboring Argentina, while Paraguay and Bolivia are also among the global top 10 producers in a $155 billion global market. Shipped in seed form or crushed into oil and meal, this versatile bean is used in a wide range of food and cosmetic products, and to make biofuels. In the popular imagination, soy is often associated with a vegetarian diet: Think soymilk and tofu. But its reality is far more carnivorous. More than three-fourths of global soy production is destined for animal feed, in which it is a key source of protein.

Despite how closely connected the soy industry is to global markets, the continent’s growers can face conditions that are anything but modern. For all of the high technology, most of the soy harvested on Fazenda Ipê’s 110,000 acres has to be trucked across the Parnaíba River on a small ferry barge that stops running at night. When AQ visited earlier this year, the dirt road from the ferry to the farm had turned half to reddish mud after a storm, and a broken-down truck caused a long pileup. There are improvements in the works: The state government is planning a bridge, and another road to the farm is set to be paved.

But improving transportation infrastructure is just one of several challenges facing the industry.

how brazil became a soybean powerhouse

In Brazil, the world’s largest soybean producer and the source of most of South America’s recent growth in this segment, the success story is neither a free-market miracle nor a triumph for state planning—it’s both.

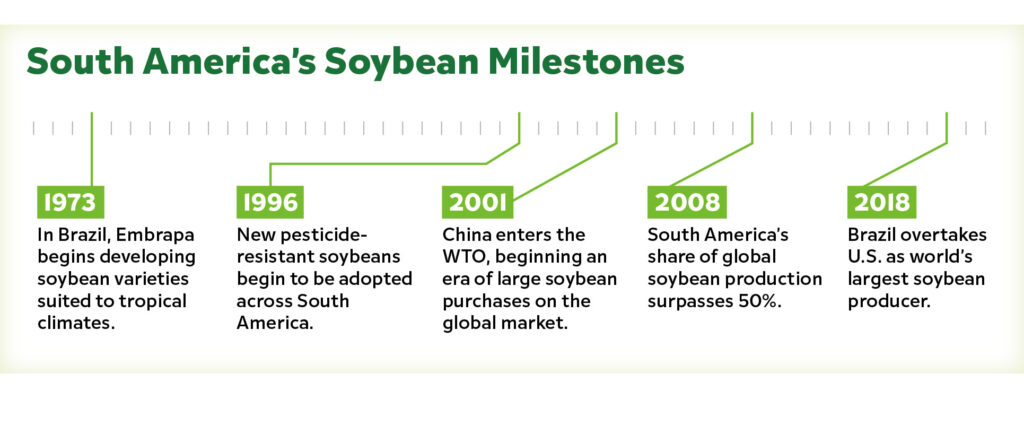

It began under the country’s 1964–85 military dictatorship, which created Embrapa, an agricultural research institute whose soybean wing soon made a major breakthrough: developing new genetic varieties of soybean that could flourish in Brazil’s tropical climates and acidic soils.

Looking for ways to populate Brazil’s sparsely settled interior, the military channeled funding through state banks to soy farmers, built roads, set up exchanges with the U.S., a major soy producer—and transformed what had been small-scale cultivation by Japanese immigrants and their descendants into an industrialized phenomenon.

“It was [an attempt] to try to create a Midwest in Brazil,” said Susanna Hecht, a specialist on Latin American tropical development at UCLA. “It’s national capital, government capital stimulating the growth.”

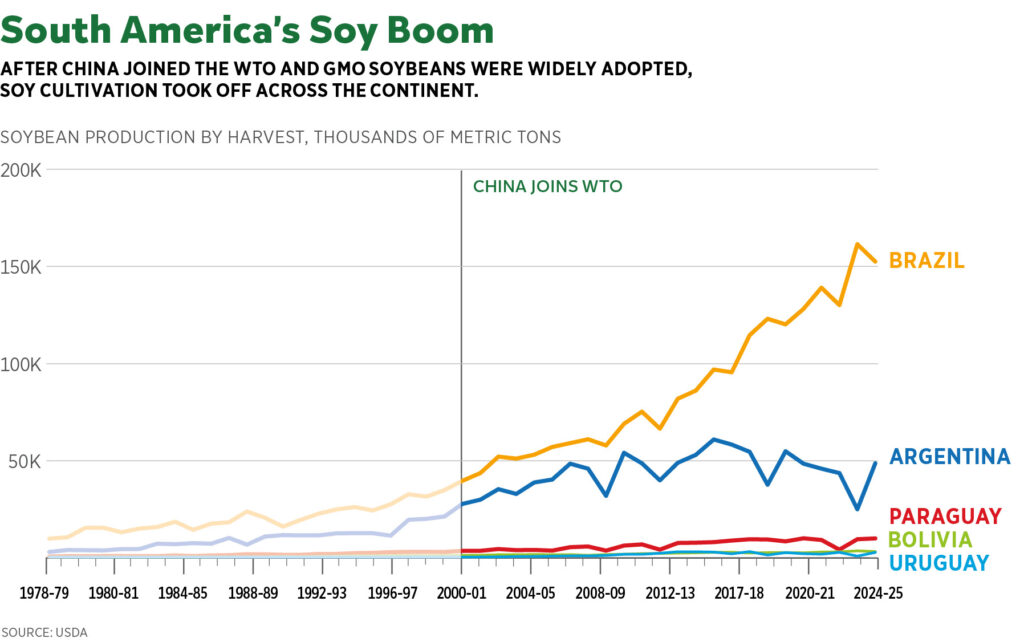

In the 1976-77 harvest, Brazil produced 12 million metric tons of soy, nearly all of it in the south. By 2000-01, that figure had tripled to 38.4 million, and the center-west had become the leading soy-growing region. The dream of economic integration of Brazil’s interior was being fulfilled.

That was only the beginning. Around the millennium, two major changes supercharged South American soy. The first was Monsanto’s 1996 release of genetically modified varieties of soybeans resistant to glyphosate, a commonly used pesticide. The second was China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. That country’s breakneck growth was creating a new domestic middle class that could suddenly afford to eat more meat—especially pork. Raising the animals to meet the demand required vast amounts of feed, and the best cheap source of protein was soybeans. Now, China had access to world markets, just as South America had figured out how to grow soy cheaply and at scale.

In Brazil, farms multiplied across new agricultural frontiers in the center-west and the north. Total production rose to 155 million metric tons in the 2022-23 harvest, a mind-boggling 100-fold expansion since 1970. Since the 2017-18 harvest, when it overtook the U.S., Brazil has been the world’s top producer, representing 40% of global supply.

In the 1970s, the median productivity in Brazil was around 1.6 metric tons per hectare. Now it’s above 3.6, said Alexandre Nepomuceno, who heads Embrapa’s soy division. “That means there’s been significant technological investment to produce what Brazil produces today,” he said.

Other countries benefited from the boom, too: Today, Argentina is the world’s third-biggest producer, representing about 13% of the global supply, and is especially successful in what’s called crushing: separating raw soybeans into oil and meal through industrial processes. Paraguay and Bolivia hold 3% and 1% of the global market, respectively.

What’s the secret to South America’s world-beating soy success? Market analysts and farmers say they have several advantages over the U.S. Cheaper land helps, but so does the climate. A longer growing season allows South American producers to wring two harvests a year out of their fields. In Brazil, soy producers often plant a safrinha, or “little harvest,” of corn after their soy harvest. At Fazenda Ipê during AQ’s visit, most plots of land that weren’t full of soy plants ready to be harvested contained knee-high corn plants, the seeds sown in the stubble of the harvested soy. That increases land productivity. South American producers can also plant without tilling the land, which cuts down on costs and lowers carbon emissions.

A favorable regulatory system that ensures genetic innovations make their way to Brazil has been the work, in part, of a powerful agribusiness lobby in Congress, the bancada ruralista. This year’s annual package of financing support to the agricultural and livestock sectors will total 400 billion reais, or about $73 billion. The money goes toward incentives and loans for farmers, made through state banks, often at reduced interest rates, to finance investments and other improvements.

limits to the soy boom?

At the time of AQ’s visit, the headquarters of Fazenda Ipê was a flurry of activity. Trucks full of soy from the fields rolled in past a checkpoint to dump their cargo into a giant sorting machine. The highest-quality beans were being set aside to be used as seed for next year’s harvest, while the rest were deposited in a towering metal silo, waiting to be trucked to the nearest railyard or river port. The seed operation here is being ramped up at breakneck speed—from 3,000 bags last year to some 14,000 this year—as Fazenda Ipê applies for a license to be able to sell its seeds to other producers, a way to add value to its operations.

Expansion is happening on other fronts, too. Fazenda Ipê’s parent company Insolo is growing its landholdings, harvesting 150,000 hectares, up from 110,000 last year. And the farm has seen major productivity gains over the last six years, its median yield rising to 72 bags of soy per hectare from around 40.

Those are impressive numbers for the surrounding area, which is expanding, too. The region around Fazenda Ipê “has grown a lot,” said Daniele Siqueira, a grains market analyst at AgRural. From Uruçuí, north of here, to Balsas to the west, “they’re new areas, and they’re at the forefront of the new frontiers,” Siqueira told AQ.

International investors are getting in on the bonanza. Faria purchased Insolo from Harvard University’s endowment fund, and down the road from Fazenda Ipê is a farm owned by the Mitsubishi Corporation.

What could put an end to this boom?

Government data showed an increase of 43% in deforestation last year in the Cerrado, threatening the government’s zero-deforestation goals.

In Argentina, it may already be over. There, soy production and area have been stagnant for more than a decade. Farmers, along with some experts, blame government policy and Argentina’s economic woes. Soy export taxes are in excess of 30%, while long-term loans are scarce and farmers can’t access newer genetic varieties used in Brazil and elsewhere.

“The government has played a negative role, on one side with taxes and on the other with a lack of support for intellectual property for genetic improvement,” said Carlos Steiger, a professor at the Universidad Austral.

Many farmers feel their sector is heavily taxed in order to sustain the country’s noncompetitive industries and hope the current, market-friendly government will change things for the better. President Javier Milei has promised to start cutting soy export taxes as soon as he can. But for now, the country’s fiscal situation is so dire he can’t spare the revenue.

“We understand that when the moment comes, and we hope it’s sooner rather than later, we’ll [be] taxed similarly to the rest of the economy and not singled out as a cash cow,” said David Hughes, co-founder of TraulenCo, an Argentine agribusiness company.

The advance of soy growing in Brazil has also been dogged, since its earliest years, by questions over land rights and usage. Fazenda Ipê was itself a subject of controversy in 2018, when a judge ruled that a subsidiary of Insolo, when it was still owned by Harvard, had engaged in land-grabbing and improperly extended the farm’s boundaries into public lands. The issue generated international media attention, and Harvard sold its stake in Insolo not long after.

Perhaps the most enduring criticism of soy is environmental: Its links to deforestation (and therefore carbon emissions), loss of biodiversity, and toxic contamination of water and soil. But producers in Brazil respond that they follow the country’s extensive regulations on land use, meant to limit deforestation and damage to ecosystems.

adding up the environmental cost

In 2006, after a Greenpeace campaign against agriculture-linked rainforest deforestation, the major multinational companies that dominate the world soy market signed an agreement pledging not to buy any soy grown on deforested land in the Amazon. The Amazon soy moratorium, as it’s known, was a substantial success, studies have shown.

It helped that the Amazon rainforest itself is not ideal for soy cultivation, said Beto Veríssimo, co-founder of Imazon, a think-tank that studies land use in Brazil. The area is too wet, and the infrastructure isn’t very good. It also has strict environmental requirements: 80% of land must be conserved by law.

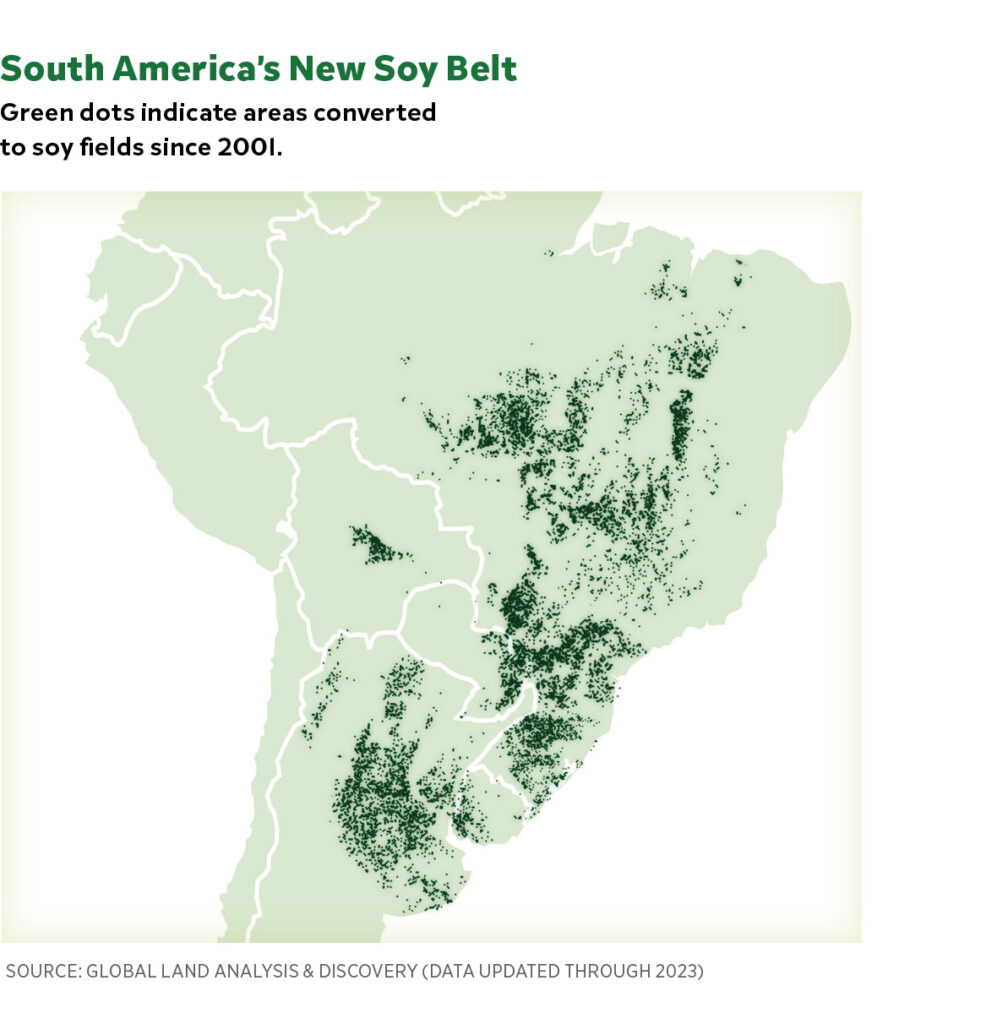

Most of the expansion of the soy frontier has instead taken place in the Cerrado tropical savanna that covers a wide swath of the country, from Mato Grosso in the center-west to the northeast. These areas are better for soy growing, since they have a well-defined dry season, and legal requirements on land use are less strict. There, the proportion of land required to be set aside for ecological reserves ranges from 20%-35%, while on the remainder, vegetation can be legally cleared.

Government data showed an increase of 43% in deforestation last year in the Cerrado, which includes soy frontier areas in Mato Grosso and the northeast, threatening the government’s zero-deforestation goals. The Cerrado has historically drawn less international attention than the Amazon—but that’s beginning to change.

Starting in December, the EU, the second-biggest importer after China, which also uses South American beans for animal feed, is mandating that all the soy it imports be certified deforestation-free. That could change how the global market titans engage with Brazilian buyers.

“The main trading companies have most of [their soy] traced, 97%, 98%, but it’s precisely in this 1% or 2% where this clearance and deforestation resides,” said Karla Canavan, vice president of commodity trade and regulation at the World Wildlife Fund. There’s worry that after the EU regulations go into effect, this untraced soy could be diverted toward Brazil’s large domestic market.

There’s no question the advance of the soy frontier has come at a cost to native vegetation, including in sensitive ecosystems like Brazil’s Cerrado and the Chaco in Paraguay and Argentina. Sometimes the process happens indirectly, with cleared land first used for pasture and later planted with soy. As environmental advocates point to the sector’s contributions to global emissions, farmers argue that the damage is limited and brings important benefits.

For Maurício Buffon, president of Aprosoja, Brazil’s leading soy growers’ association, the economic and social development that soy brings to the agricultural frontier in Brazil’s traditionally poor northeast is worth the consequences of land use change, as long as environmental regulations are respected.

“It’s the only way to take these populations out of poverty,” said Buffon, who told AQ the northeast “won’t be devastated” by another 3%-4% of its territory going to soy cultivation, on top of the current 4%. “If we get to 8%, it’s a very different situation for the region,” in terms of socioeconomic improvement, he said.

Veríssimo is less certain. More clearances could exacerbate climate-related challenges facing producers, he said. Brazilian soy is mostly grown without irrigation, which keeps prices down. But the soy-growing belts in Mato Grosso and especially in the northeast depend on what scientists call “flying rivers”—belts of atmospheric moisture that bring rainfall from the Amazon rainforest. Recent studies suggest deforestation is threatening to disrupt those flows, potentially imperiling yields.

In interviews, soy producers tended to downplay climate risks, saying they only see the usual cyclical weather changes—an El Niño here, a La Niña there—and emphasized their ability to adapt to unpredictable weather, as Fazenda Ipê did this year. But in the meantime, some farms, including Fazenda Ipê, are toying with the idea of upping their irrigation capacity.

Farmers “want to be optimistic,” Veríssimo told AQ. “But the science is very clear right now. … We are very exposed to climate change scenarios.”

an uncertain future

The last two harvests have been a wake-up call for South American soy producers. In 2022-23, a brutal drought in Argentina cut its harvest in half—and brought the national government to its knees, sapping it of foreign reserves and helping spoil the incumbent party’s bid for the presidency. This year, Brazil suffered a double blow: bad conditions in the field, thanks to drought conditions, on top of lower prices. But even with Brazil’s production down, a better year in Argentina and the U.S. led to oversupply in the global market. Chinese growth was slowing—and some indicators suggested it was taking a toll on demand for soybeans. But acres planted in Brazil were still going up, and so were yields.

Could South American soy be headed for a major setback—the end of the boom?

“The problem is that Chinese demand is very stagnant,” said Siqueira, the grain market analyst. “In years when the weather is good there will be too much soy. [Without] new markets, whether for soy or its derivatives, this is a worry for the future.”

“Today, (soy) is clean energy for the world.”

—Ricardo Faria, Insolo owner

Pedro Dejneka, co-founder of MD Commodities, a market intelligence firm, thinks the problem can only be fixed through lower prices. “We need to take prices low enough where the United States is going to have to decrease soybean area” by switching acres to corn, he told AQ.

There were fears China could start producing more of its soy domestically, seeking to reduce its dependence on imports from the Americas, or that it might encourage African countries with similar climates to adapt Brazil’s soy-growing technology and know-how.

Finding new global markets to fill in for China’s slowdown could be difficult. Rapid economic growth in India, where vegetarianism is more common, might not translate into high levels of soybean demand, driven principally by meat eating. Even Brazil’s president is openly broadcasting his hopes for a global shift to keep the boom going. “Every day I pray that even the Indians go back to eating meat,” said Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at a business forum in July.

Biofuel might be the next frontier: Analysts cite the possibilities of biodiesel, a fully renewable diesel fuel that has advantages over the current mix of biofuel and regular diesel that’s sold in countries like Brazil.

Ricardo Faria, the Insolo owner, struck a more confident tone. “I don’t believe Africa will steal our market,” he told AQ. “We have this capability that was [the product of] a long-term educational system of knowledge, and we have very well-structured laws of protection of property that Africa doesn’t have.”

What about oversupply in the global market? Faria saw a possibility for a “perfect storm” for producers, if global supply outstrips demand. But if global grain consumption continued to increase by around 1% per year, as it has up to now, and with biofuel demand increasing, he told AQ, the cycle can repeat itself.

“Two or three years after the perfect storm for [producers], the perfect storm for consumers can happen, and prices skyrocket.”

At Fazenda Ipê, there’s scarce time to contemplate the future of South American soybeans—there’s too much work to do. Despite the cutting-edge technology, farming still requires long hours of toil. During AQ’s visit, operations on the farm started before dawn and ended after dark.

Standing amid rows of soybeans ready to be harvested, it looks like the fields here go on forever, stretching to the horizon where they meet a wide, pale blue sky, studded with anvil-shaped clouds. But it’s an illusion. The farm is really perched on an enormous plateau, one of many here in southern Piauí that alternate with lowlands less suitable for farming. It goes on for a long way, but it has its limits.