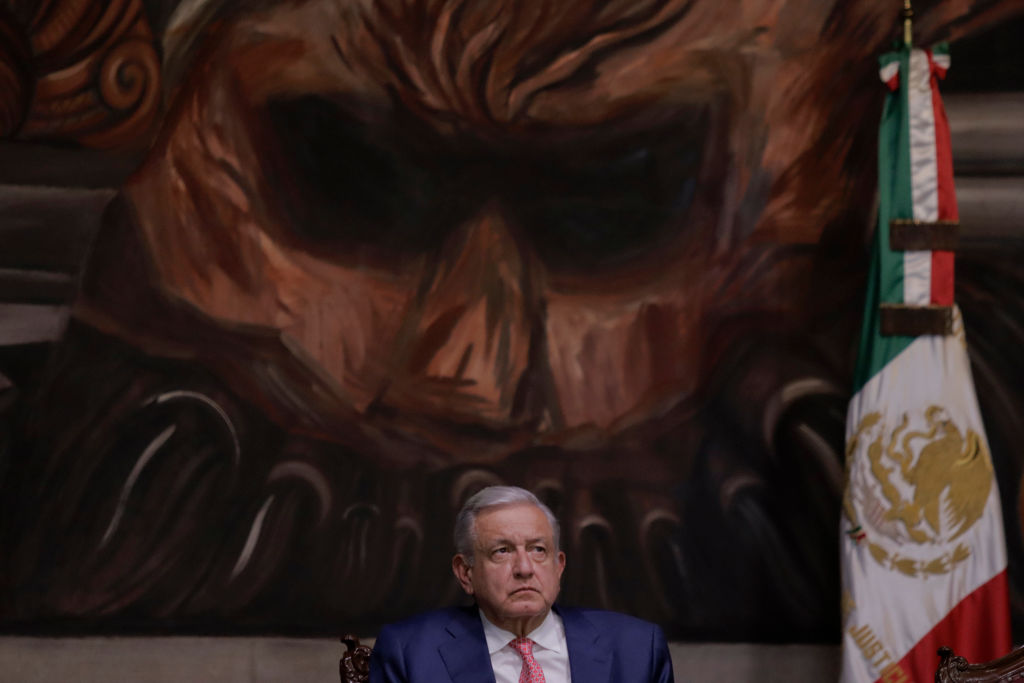

As President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s term nears its end later this year, his battle against Mexico’s independent institutions is acquiring a new focus: the Supreme Court.

AMLO is pursuing an initiative for justices to be elected through popular vote, just as the high court is set to decide on a number of key issues, including a recent electricity industry law, the nationalization of lithium, and a dozen state-level electoral reforms.

Across the first five years of his six-year term, AMLO’s attacks on Mexico’s independent institutions have ranged from pushing constitutional and legal reforms that would diminish their powers, to aiming public comments at their leadership, to budget cuts and more. The Supreme Court has often served as an effective counterweight—but it, too, is in AMLO’s crosshairs.

Just last month, in an unprecedented decision, AMLO appointed Lenia Batres Guadarrama to be the next Supreme Court justice—as permitted by the constitution after, for the second time in a row, none of his three nominees received the necessary supermajority vote in the Senate. Until January 4, when she joined the top court, Batres Guadarrama was working for AMLO’s government as deputy advisor for Legislation and Regulatory Studies in the legal department of the federal executive. A close ally of AMLO since 2002, she has mainly dedicated her 23-year-long career to politics, raising questions about her technical legal qualifications.

The appointment represented the first time in Mexican history that the president has directly chosen a member of the top court, drawing concern about the separation of powers and erosion of the mandate bestowed on the legislature.

An active top court

Recent years have seen the Supreme Court intervene against an overbearing executive and a sometimes overreaching legislative. For instance, in June 2023, the Court ruled that a 2021 presidential decree on hydrocarbons was unconstitutional since it violated the principles of competition enshrined in the Constitution. The decree aimed at eliminating the Energy Regulating Commission (CRE)’s faculty to use asymmetric regulation, which allows competition between Pemex and private market players, and sets a level playing field.

The Court was also decisive regarding a 2023 attempt to change Mexico’s electoral laws. The ruling Morena party passed an electoral reform last February (after a failed, more ambitious attempt at a constitutional reform). Among other measures, the law imposed a reduction of the electoral institute’s staff by 86.5% and cut its budget by $290 million (MXN 5 billion), as well as limited its authority over political parties and candidates. The INE leadership overtly opposed the bill, and civil organizations and citizens expressed strong opposition against its implementation with the “INE no se toca” protest on February 26, which gathered thousands of people (estimates range between 100,000-500,000). In two rulings between May and June, the electoral reform was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, ruling its approval involved significant violations of the legislative process.

In these and other recent rulings, the Supreme Court has demonstrated that there are still critical legal recourses to challenge unconstitutional changes, even in the context of substantive changes in the court’s composition via the appointment of supporters of the executive and budgetary reductions—including a 10.6% cut from 2018-2024—that have been aiming at curtailing its influence.

Protecting institutions

The Supreme Court has played an important role in seeking to protect other institutions from attempts to weaken them, for example through neglecting or delaying appointments to their governing bodies, creating a de facto paralysis of the institutions. Such has been the case of INAI, Mexico’s transparency body, which is awaiting new appointments for three out of seven of its members, impeding its operation.

The Supreme Court issued a resolution last July concluding that the Senate had ignored its responsibilities and needed to vote for the new commissioners. Yet the ruling Morena party prevented consensus from being reached during the December 2023 legislative sessions. Instead, the current commissioners appointed a new president of INAI, who will lead the battle that will come their way as the president signals he may try to get rid of the institution altogether, as stated in one of his daily press conferences in December.

Ironically, one of the most essential takeaways from AMLO’s presidency is the utmost importance of independent and technical institutions for democratic resilience, transparency, accountability and economic stability. But all things have their limits. How long can these institutions resist the political onslaught and maintain sound performance? The future of checks and balances between the three powers and that of independent and technical institutions will largely depend on the democratic character and the limits imposed on the new president of Mexico, who will take office on October 1 later this year.

The first enormous challenge could come in December, when the new president will have to put forward candidates for a new justice. If Claudia Sheinbaum wins the election and another Morena ally is chosen for the high court, the total will rise to four. Rulings on unconstitutionality require a supermajority of eight out of the court’s 11 members, meaning Morena appointees could block action against laws put forward by the party—which would put in danger the Supreme Court’s role as guardian of constitutionality in Mexico.