This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025

In December 2017, a year and a half into his five-year term, Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (PPK) reversed a campaign pledge and issued a pardon for controversial former President Alberto Fujimori. The move was meant to bargain with parties in Congress that supported Fujimori, but proved so unpopular that PPK was soon forced out of the presidency, becoming one of more than 20 presidents across Latin America who have not finished their terms since the 1980s. What’s behind this trend?

In Why Presidents Fail: Political Parties and Government Survival in Latin America, Christopher Martínez combines rigorous quantitative analysis with detailed case studies for seven countries in South America to account for why some presidents are forced out of office before the end of their terms. Using data for countries since the early 1980s (or after the third wave of democratization), Martínez suggests that the resilience of party systems is a key factor in determining why some presidents are able to survive political crises—the weaker the party system, the harder it is for presidents to successfully navigate major problems.

Why Presidents Fail: Political Parties and Government Survival in Latin America

By Christopher Martínez

Stanford University Press

Hardcover

324 pages

For specialists, Martínez’s argument is not novel. As Martínez himself discusses in the introductory chapter of the book, the importance of political parties for a well-functioning democracy has been known for decades. Similarly, party system institutionalization—a concept that attempts to measure the stability in the party system, the roots of political parties in society, and the ability of parties to successfully represent the different interests and views prevalent among the electorate—has been central to the study of democratic stability for decades.

Prior works on Latin American presidential democracies have noted the importance of a strong and stable party system for the development of competitive democracies in the mid-20th century and for the consolidation of democratic governments after authoritarian rule in the later part of the century. Scholars who studied democratic consolidation underlined the importance of a stable, competitive and institutionalized party system for democracy to thrive. Others who looked into why some democracies have experienced backsliding or full reversal noted the weakening party system as a key factor.

But Martínez contributes to the debate on the reasons why presidents fail by providing detailed and carefully crafted statistical analysis for 18 Latin American countries from 1980-2020 and analyzing the experiences of seven countries with different levels of party system institutionalization (from low to high: Peru, Ecuador, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil, Argentina and Chile).

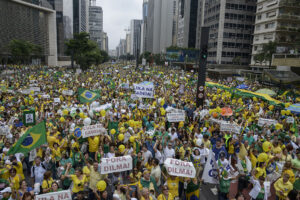

Martínez’s book is thought-provoking, showing that while more popular presidents usually do better, having a fragmented party system or little support in the legislature makes them more likely to struggle. But some questions remained unaddressed. Since Martínez does not discuss the breakdown of democracies in the 1960s and 1970s in some of these countries, he does not address the question of why seemingly institutionalized party systems failed to prevent the fall of democratically elected presidents. Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay experienced full democratic breakdowns—far worse than cases when presidents are removed before their term ends. But strong party system institutionalization did not prevent the breakdown of democracy in the past and might not be a strong enough safeguard to prevent democratic backsliding, as the case of Venezuela showed in the 1990s and the case of El Salvador clearly shows today.

Martínez’s rich discussion of Paraguay exemplifies how the study of parties requires looking at the party system level and at the individual party level. While most outside observers know that the Partido Colorado has been dominant for decades in Paraguay, most people are unaware that there is plenty of competition within the Colorado Party between the two dominant and established factions, Honor Colorado and Fuerza Republicana. When one party becomes so dominant, there is often strong competition among factions within the party.

Party systems often change—aligning, dealigning, realigning. Individual parties emerge, decay and vanish. If an emerging party replaces old parties, the party system might survive and remain institutionalized even if the number and labels of the political parties change. For example, while in Chile the once- dominant Christian Democratic Party is no longer a major player in national politics, the country continues to have a strong level of party institutionalization. Party system institutionalization might or might not require strong partisanship—the academic jury is still out on whether a country where few people identify with political parties can still be labeled as having a highly institutionalized party system.

Those who wonder why some presidents fall in the midst of political crises and others survive and are able to complete their terms will find, in Martínez’s book, a compelling argument in favor of having democracies with a strong party system and with individual parties that have strong roots in society. Martínez joins an accomplished group of scholars that have studied the party system and illuminated readers about the importance of having stable, strong and reliable political parties.

But the book—like most of the previous major books on this subject—does not take on the very important question of why some countries have high levels of party institutionalization and others do not, or why many countries are seeing partisanship decline and parties evolve into personalist electoral vehicles for populist leaders. Answering that question is a tall order for a discipline that often has more answers than questions. By highlighting the importance of party system institutionalization for democracy, Martínez’s book reminds us that those countries that have an institutionalized party system should work hard to preserve it. A strong party system is the best defense system for the survival of democracy.