Oil and gas prices are at multi-year highs — for now. But with a rash of net-zero pledges from oil-producing and oil-consuming nations alike coming from COP26 negotiations in Glasgow, the future of Latin America’s oil industry is in jeopardy. The region’s national oil companies, especially in a few laggard countries like Venezuela and Mexico, must act quickly or be left behind by the global energy transition, with grim consequences for national economies.

It’s unclear how long the process of decarbonization in the world energy market will take, but what is clear is the threat it presents to the market for oil and the rents that come from its extraction. Latin America especially stands to lose from a decline in oil demand: It has the second largest oil reserves in the world after the Middle East. But Latin American oil production involves higher costs and higher carbon intensity than the Middle East, which makes it less resilient to drops in demand. The faster the decarbonization process ends up being, the more disruptive it will be for the region.

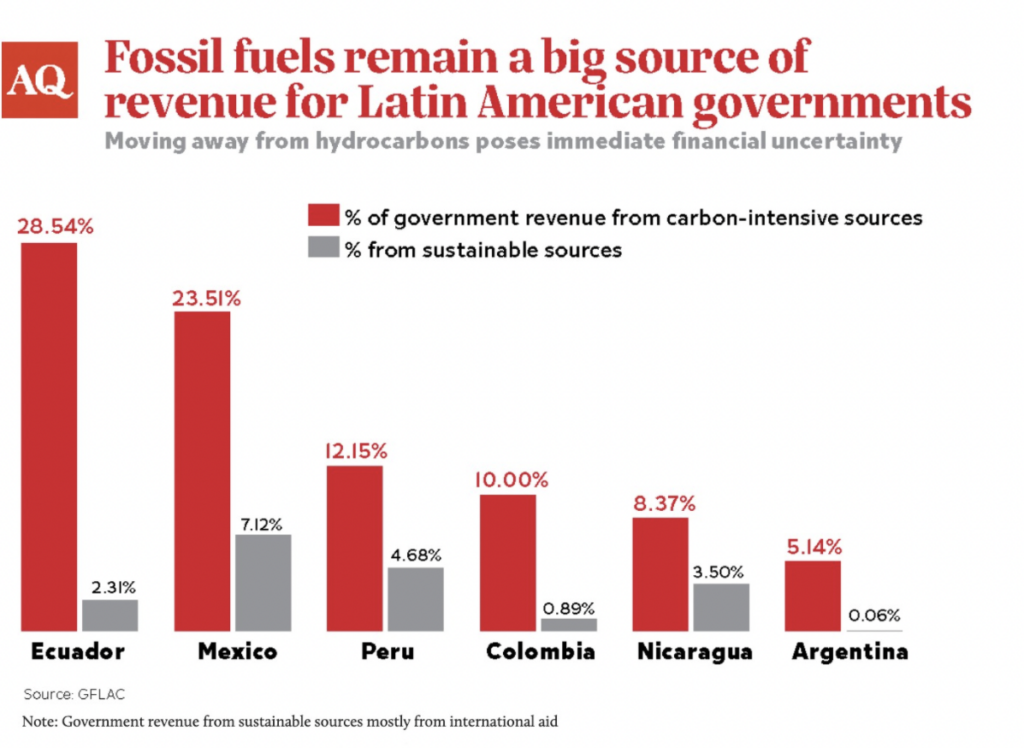

Venezuela, Ecuador, and Colombia are particularly dependent on oil exports and revenues. Bolivia and Trinidad and Tobago depend on natural gas. The small nation of Guyana is poised to become the largest per-capita oil producer in the world, just as the window for developing its reserves may be closing. Though Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico are not as oil dependent, oil and gas are among the largest industries in each country in terms of fiscal revenues, exports, and investments. The Latin American national oil companies also have significant macroeconomic importance as providers of oil rents, generators of foreign exchange receipts, issuers of foreign debt. When they are listed on stock markets, they are among the largest companies in terms of market capitalization.

Investment by large international oil companies (IOCs) looks set to cool off. Recent announcements by some of the largest European IOCs (BP, Shell, Total) tout accelerated plans to diversify their business models into renewables. Judicial pressure on Shell in the Netherlands, as well as shareholder pressure on the boards of Exxon and Chevron, suggest the appetite of the traditional “oil majors” for investment in Latin America could drop or change focus into low carbon projects. The pressing question is whether they will be replaced by national oil companies from China and India, or perhaps private equity investors or smaller companies.

It’s too soon to pick winners and losers, given the uncertain pace of the energy transition, but it’s clear who is currently better poised to adapt. Among the major national oil companies, Brazil’s Petrobras and Colombia’s Ecopetrol, the only national oil companies in the region to pledge net zero by 2050, are emerging as leaders in the region. Petrobras is positioning itself as a low-carbon producer able to survive in a low oil-price environment, even deep into the energy transition. Petrobras has stated that it can produce its prolific “pre-salt” offshore fields at $35 per barrel. At 2.83 million barrels per day of oil and gas production, Petrobras is the largest producer in the region and the only national oil company with a clear path to significant production growth in the next five years. The company has been shedding assets as part of a divestment program responding to the need to deleverage and concentrate its expenditures to fulfill its production targets of 3.3 million barrels a day by 2025. Becoming leaner and concentrating efforts on making its pre-salt fields less carbon intensive might be Petrobras’ niche as a geopolitically attractive alternative to OPEC.

Colombia’s Ecopetrol, meanwhile, is leading the pack in terms of diversification of its business model. Ecopetrol is rethinking its business strategy, diversifying into non-fossil sources of revenue, with the acquisition of ISA, an electricity transmission company. While offshore gas might have potential, Colombia’s and Ecopetrol’s low reserves relative to production and potential environmental concerns about shale leaves the field open to bold moves into other sources of energy, with the country even exploring hydrogen.

On the other side of the spectrum, Venezuela’s PDVSA and Mexico’s Pemex are clear stragglers with few immediate prospects for improvement. Without a significant policy U-turn, these two national companies and their oil assets will be at the forefront of the discussion about stranded assets in the region. Exploitation of Mexico’s deep-water and shale reserves are being put on hold by a state-centric oil and gas policy that is scaring off private investment. With its strategy directed by the government of statist president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), Pemex is sinking money into expanding refining capacity at a time of worldwide refining overcapacity, making the Mexican company less resilient to the energy transition. Ironically for AMLO’s defense of national energy sovereignty, these decisions are making Mexico more dependent on imports to satisfy its present and future energy needs, given the budget constraints of both Pemex and the government.

Venezuela, of course, looks worse. The severity of the institutional deterioration of both PDVSA and the government, macroeconomic policy dysfunction, anti-private sector policy framework, significant geopolitical constraints (i.e., sanctions) are all serious obstacles to Venezuela’s ability to navigate the energy transition. The national oil company — with its high carbon intensity and high methane emissions, not to mention its serious governance issues — creates significant liabilities for a future reconstruction of the oil industry. Only a significant change in the current political and policy framework would allow Venezuela a chance properly to tap into its ample gas resources, develop its potential for carbon storage and maximize its renewable energy potential.

That leaves Argentina and Ecuador, whose national oil companies — YPF and Petroecuador, respectively — are still a question mark. The high share of natural gas in YPF’s portfolio means the company has a head start in the decarbonization strategy vis-à-vis some of its peers. Its ability to generate returns on investment quicker with short-cycle shale production plays in its favor. But poor financial performance, the country’s macroeconomic imbalances, the government’s solvency issues, and the high cost of its shale, are worries. Ecuador, meanwhile, is trying to enact more pro-private sector policy changes, while environmental concerns around oil production could disrupt its plan to aggressively increase oil output in the next few years.

As for Guyana, beneficiary of an ongoing bonanza after the discovery of a large reserve in 2015, the small country seems intent on maximizing revenues over the next ten years, potentially reaching 750,000 barrels a day by 2025. As a newcomer lacking technical capacity, Guyana is relying on a consortium of international oil companies led by Exxon. A realization that the window of opportunity is closing is serving as a check on nationalist tendencies that have inflicted damage on some of the country’s regional peers, particularly in times of high oil prices. The challenge for Guyana and its neighbor Suriname will be to succeed where others have failed and use proceeds from the oil boom wisely.

The energy transition also represents an opportunity for the region’s energy importers. Chile, the most conspicuous example, has made significant inroads into the renewable space and it is today the country with the most potential on hydrogen, which many see as the fuel of the future. The country also stands to benefit from the increased demand for critical minerals for electrification like copper and lithium.

The energy transition represents real challenges, but also opportunities for countries and national oil companies in Latin America. With oil prices currently high, the time is right for the region’s oil industry to take note of decisions being made today to adapt to a net-zero world and use their windfall profits to plan decarbonization strategies. That will ensure they retain access to capital and even export markets in the carbon-neutral future.

—

Palacios is a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

Monaldi is a fellow at, and director of, the Latin American Energy Program at Rice University’s Baker Institute.