For good reason, the Amazon is under a global spotlight. But this spotlight, focused on Brazil, Colombia and Bolivia, treats the accelerating destruction of Venezuela’s Amazon as an afterthought. Leading international organizations, environmentalists and scientists tend not to address this vital region in their discussions or programs. If they seek to avoid the dreaded “tipping point” in the Amazon’s destruction, they must acknowledge what is occurring in Venezuela.

Around 60% of Venezuela’s territory—550,000 square kilometers—belongs to the Amazon biome, accounting for 8% of biome’s expanse. Perhaps most significantly, Venezuela accounts for nearly 20% of the Guiana Shield, a globally unique geological formation about 1.7 billion years old. It is heavily forested and is one of the Amazon biome’s gems. But Venezuela has the fastest deforestation rate in the Neotropics (the tropical regions of the Western Hemisphere) and the fifth-fastest rate in the world, with a total of 1.4 million hectares lost between 2016 and 2021.

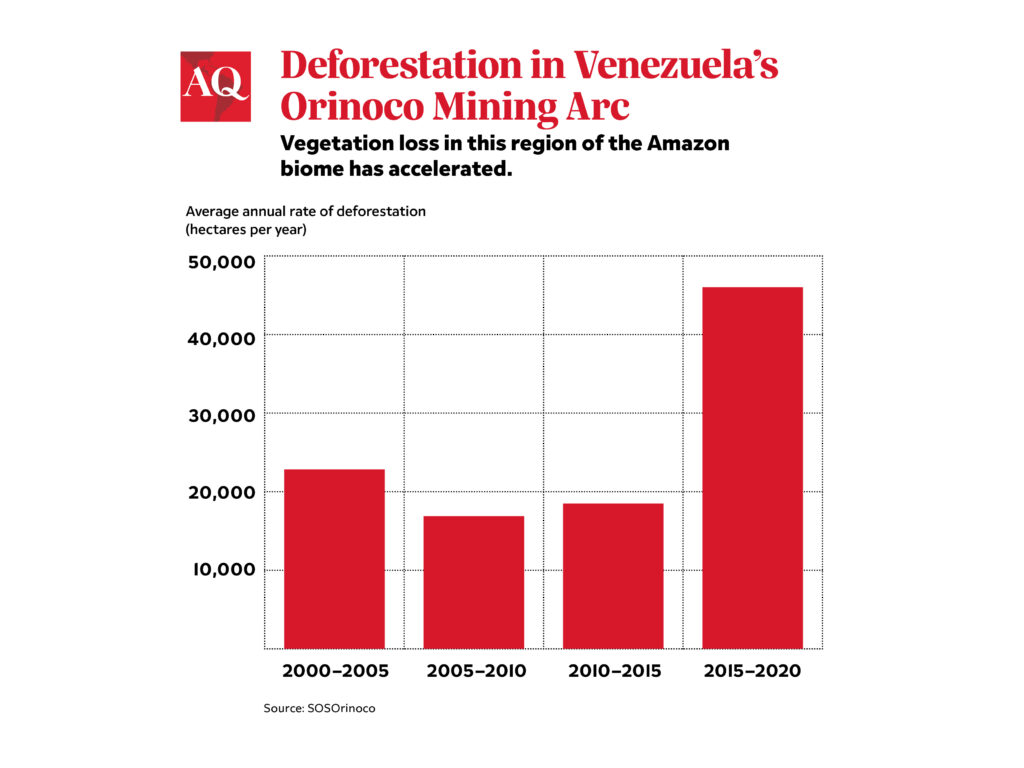

One of the major drivers of this deforestation is the policy framework surrounding the Arco Minero de Orinoco (AMO), or Orinoco Mining Arc. In 2016, the government of President Nicolás Maduro illegally established the AMO without the approval of the National Assembly, assigning it 12% of the country’s territory—an area larger than Portugal.

The move was designed to lend mining activity an appearance of legitimacy and regulation. However, the AMO has driven mining activities into territory far beyond its supposed boundaries. This includes pristine protected areas, including the Canaima National Park World Heritage Site, home to Angel Falls—the planet’s tallest waterfall—and the ancestral territories of various Indigenous peoples, including the Pemon, Yanomami and Yek’wana, among others.

Now, a chaotic rush of natural resource extraction of gold, diamonds, coltan and rare earths are devastating Venezuela’s Amazon and especially its Guiana Shield region. The AMO has encouraged informal mining, easing permitting and inspection processes and allowing mines to skirt environmental regulations. Under this framework, illegal armed groups allied with the government continue to run especially destructive mining operations, kicking up much of the wealth they extract to senior leaders in the military and government. Civilian and military authorities who respond to Maduro and his clique control access to fuel, mercury, motor pumps and mining areas—and profit handily from this control.

The Economist recently observed that the world is entering an era of open-source intelligence gathering. The Maduro government no longer has a monopoly over information on this region, however remote, and the impact of its policies on people and the environment. SOSOrinoco and other organizations like Bellingcat have revealed the criminal dimension of the Maduro government’s mining policies by mapping the expansion of the illegal mining in Venezuela’s Amazon. SOSOrinoco exposed, for example, a huge complex of illegal mining within Yapacana National Park, which has become a stronghold for Colombian guerrillas. Yapacana is the largest illegal mining area in the entire Amazon biome.

In September, a UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) fact-finding mission published a long-overdue report that details the human and environmental horrors occurring in Venezuela’s Amazon. Its findings, along with reports from the OECD, Transparencia Venezuela and SOSOrinoco, among others, show that widespread human and environmental rights abuses are due not to simple negligence on the part of the Maduro government. Rather, they are a result of its actions and policies. In September, an OECD report stated that “research indicates that all gold originating within Venezuela should be considered high-risk.” Venezuela has refused to sign the Escazú Agreement or ratify the Minamata Convention, which curtails global use of mercury.

And yet, international discussions and programs tend to ignore the environmental chaos unfolding in Venezuela. Organizations like World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and others all left Venezuela in the early 2000s. Like other important advocacy groups, Greenpeace has never launched a campaign to protect the Amazon forests of Venezuela. Important funders such as the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation don’t include Venezuela in their conservation programs.

So why don’t environmentalists give the same attention to Maduro as to President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, for example? For its part, Norway may be prioritizing its short-term role as facilitators of negotiations between Maduro and the Venezuelan opposition.

Illegal land grabs, deforestation and an out-of-control mining rush in protected rainforest areas have created a perfect storm of environmental degradation and humanitarian crisis. The international community should react accordingly and include Venezuela’s Amazon in their planning and programming. The Amazon biome doesn’t stop at any national border, so the international community’s discourses about the Amazon shouldn’t either.

—

Vollmer Burelli is the executive director of V5Initiative.org and the founder of advocacy group SOSOrinoco.org, focused on the Venezuelan Amazon.