Holding credible elections in a region where people tend not to trust government is difficult enough. Add a pandemic, and the stakes get that much higher.

With a slate of elections scheduled for this and next year throughout Latin America, policymakers are struggling with the questions of how and when to move forward. Meanwhile, with protests discouraged and votes postponed, citizens have been left with fewer ways to hold their leaders to account.

“The fundamental dilemma is how to protect the health of citizens while also protecting the institutional health of the country,” Jennie K. Lincoln, a senior advisor at the Carter Center, told AQ.

COVID-19 is peaking in Latin America as disillusionment with democracy is on the rise. The latest Latinobarómetro survey reveals that Latin Americans’ trust in government fell from 45% in 2010 to 22% in 2018. That means decisions over when to hold elections are about much more than just picking new dates.

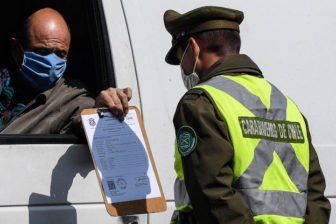

Chile is a case in point. Mass demonstrations in 2019 led to the promise of a constitutional referendum in April, which many hoped would mark a turn toward the kind of social change protesters demanded. But the plebiscite has now been rescheduled for October, with regional elections pushed to April 2021. That could reinforce protesters’ view that the government is unresponsive to their demands, said Columbia University professor María Victoria Murillo.

“People thought there would be a plebiscite, and now they can’t even go out and protest, or vote or expect any change in the current context,” Murillo told AQ. “(The delay) adds to the crisis of legitimacy that the Chilean government was already suffering.”

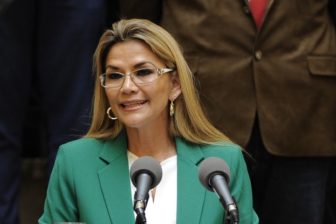

A delayed vote is also raising concerns in Bolivia, where an already rescheduled election was seen as a way to turn the page on a democratic crisis that began with former President Evo Morales’ resignation in November. Interim President Jeanine Áñez’s decision to suspend the re-vote, citing health risks, led some observers to question whether she might try to use the outbreak as cover to extend her time in power.

In response, Bolivia’s legislature, controlled by Morales’ MAS party, passed a law stating that the election would need to be held before Aug. 2. Áñez quickly condemned the decision, though Bolivia’s electoral court has since negotiated a September election date, managing to reach a consensus in Congress. Still, the delays have heightened the atmosphere of uncertainty and distrust in the country.

Even in parts of the region not already dealing with political upheaval, voters may not trust outcomes if elections don’t take place as scheduled. Turnout is likely to be poor, and those who do show up at the polls will risk exposing themselves to infection. International election monitors, a mainstay in Latin America, may deem it unsafe to send observers, even though their mission will be more critical than ever, said Ernesto Calvo, an elections expert at the University of Maryland-College Park.

“Observers will have to keep an eye on the attempts to manage social distancing as a way to make political gains for some political actors and not others,” Calvo told AQ.

It’s a no-win situation for policymakers. Delays risk exacerbating social discontent and government distrust, while pushing forward could lead to a spread of the virus. On balance, countries in the region have so far chosen the first option. Uruguay, Peru, Paraguay, Mexico and Argentina have all delayed upcoming local or municipal elections. In Brazil, Chamber of Deputies President Rodrigo Maia said in May that congressional leaders were “almost unanimous” in their view that the October municipal elections will be rescheduled.

But postponing may be easier in some countries than in others, given voter expectations and the logistical challenges of running elections in general.

“The whole electoral process is labor-intensive and takes months to organize,” Lincoln said. “This is challenging in normal times, especially in countries like Ecuador and Bolivia that have challenging geographies.”

Though Ecuador’s government has given no indication that it will try to postpone a general election in February 2021, analysts expressed concern over the election given recent unrest. Thousands of Ecuadorians broke quarantine orders in late May to protest against the Moreno administration’s budget cuts and other austerity measures.

“The elections will be complicated. Ecuador is one of the worst-hit countries in the region by COVID-19 and it’s a very intensely polarized country,” Calvo said.

Ultimately, whether or not countries decide to hold or postpone elections may be less important than whether or not governments follow clear institutional steps to arrive at a decision, Calvo said. “You have to work around the pandemic, not change the rules.”

If countries do go ahead with elections, some strategies could help promote safety via social distancing and sanitary protocols. Toby James, an elections specialist at the University of East Anglia, recommended early voting as a way to comply with social distancing, describing it as “a low-tech deliverable.”

In theory, countries with a functional postal system, like the United States, could give citizens the option to vote by mail. But even then, structural problems in the region’s postal systems make it unlikely as a widespread alternative to in-person voting.

“There’s not an easy fix for these issues,” James told AQ. “Democracy is going to be hurt when you hold an election and when you don’t hold an election.”

—

Rauls is an editorial intern at AQ and a policy intern for AS/COA’s Anti-Corruption Working Group.

Sweigart is an editor at AQ and a researcher for AS/COA’s Anti-Corruption Working Group.