Listen to a conversation with former President of Costa Rica Luis Guillermo Solís on The Americas Quarterly Podcast

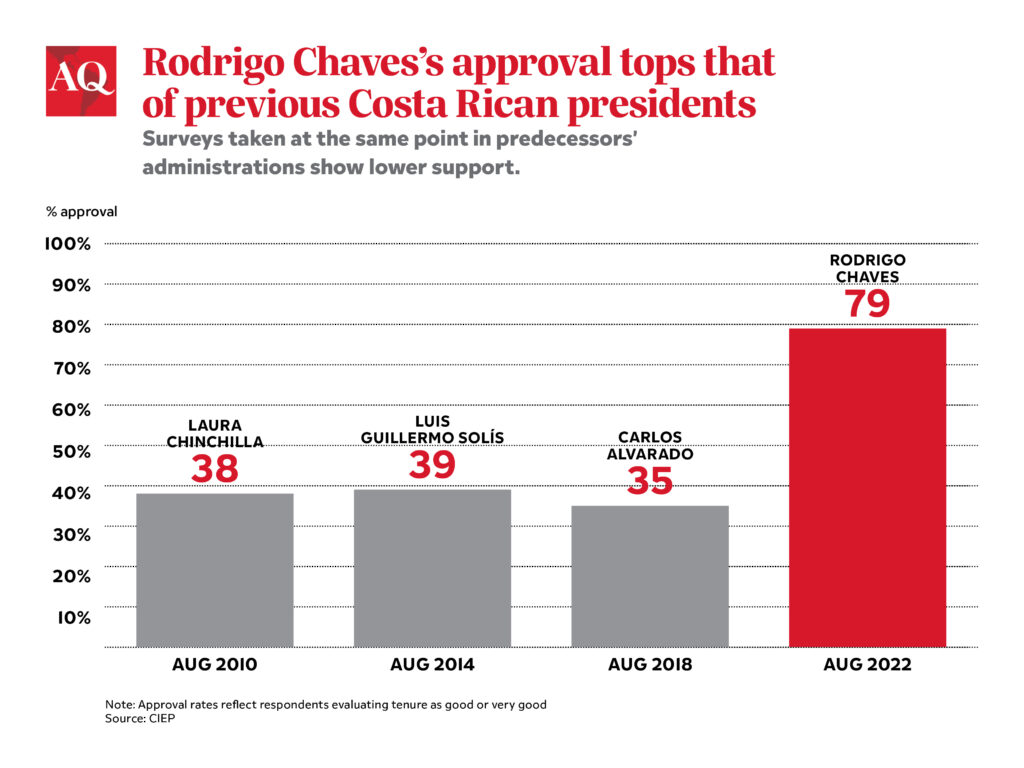

Rodrigo Chaves’s administration in Costa Rica is facing multiple international and local challenges in its first five months, from high oil prices and a fiscal squeeze to a conflictive relationship with the legislative branch. However, a new, domineering style seems to be in part helping him so far to enjoy approval of nearly 80%, according to recent surveys. Observers are left wondering how long this can last if the administration’s results continue to be scarce.

Besides high worldwide prices for the gas and diesel Costa Rica must import, the country faces an annual inflation rate of 12.13% as of August—the highest since March 2009. It has been difficult for the new government to prevent Costa Ricans from suffering new hardships after the ravages of the pandemic. At the same time, Chaves’s government has been in a race against time to get Congress to approve the issuance of $6 billion in Eurobonds (the country’s public debt bonds sold in international markets) designed to finance the country’s high external debt.

Tensions have emerged between the executive and other branches of government. In less than two weeks, Congress has overridden two presidential vetoes, while on October 21, the Constitutional Court annulled the government’s decision to suspend operations at Parque Viva, an entertainment center belonging to Grupo Nación, a news media company also funding the newspaper La Nación with which Chaves has particularly clashed. The court considered the government’s decision an indirect violation of the freedom of the press. International organizations have also issued warnings over the Chaves administration’s intimidation of media.

Four factors characterize the first five months of the Chaves administration: high popular support despite limited fulfillment of campaign promises, the administration’s limited ability to advance its agenda in Congress, a newly centralized and confrontational leadership style—and open clashes with the press.

Experts expected a short honeymoon period for Chaves’s government, due to the volatility of support in the electoral runoff and the fact that his electoral majority had been consolidated in part by the rejection of his opponent’s candidacy. Defying these predictions, Chaves has managed to generate trust in broad sectors of the population, according to opinion studies in August and September by CIEP and IDESPO. His decrees have garnered widespread approval, including one eliminating the fixed minimum price of rice, and others removing limits on the importation of medicines and suspending a contract with Spanish company RITEVE in charge of the obligatory technical vehicular inspection, whose operations had been criticized for its high prices.

Limits to Chaves’s popularity

Chaves’s success in employing the bully pulpit has not blotted out citizens’ concerns about the situation the country faces. Of those who have a favorable or very favorable opinion of the government’s work, 78% also have a negative opinion regarding the management of the economy according to CIEP, as his campaign promises to reduce the cost of living, reactivate the economy and limit public spending have not been fulfilled.

Still, Costa Ricans seem to be giving the new president a chance, although it is uncertain how long that vote of confidence will hold. Chaves’s leadership style and his way of doing politics have contributed to the perception that he is leading a government of change, if more through form than substance. Chaves is depending on the direct and abrasive communication style that won him the election. That strategy has resonated widely among those who are dissatisfied with the traditional political class and thirst for change.

Leadership so far has been centralized and concentrated in the figure of the president, who wields greater power over his cabinet. Televised press conferences held every Wednesday have become a space to call ministers to the stand and demand compliance with measures and deadlines before the media. That space is also used to further polarize the political environment, expose Congress representatives who oppose his policies, and demonize the media that questions him. The parallels of these conferences to Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s mañaneras have become apparent. “Rogue press” and “fauna”—the latter a comparison between journalists and animals—are just a few of Chaves’s preferred expressions for media outlets. Social networks have become echo chambers of his narrative. Despite its reputation for greater stability, it’s clear Costa Rica is not immune from the populist rhetorical strategies used by other governments in the region.

The government’s broad level of popular support, however, will be difficult to sustain over time if it depends exclusively on its communication strategies with no prompt evidence of results. Much depends on the measures that the administration can adopt despite a fragmented Legislative Assembly. The administration’s difficulties in presenting projects to the legislature, and the weaknesses of the emerging congressional delegation of the PPSD—the party that Chaves joined just a few months before the election and which managed to elect only 10 out of 57 deputies—to set the agenda, led to an unproductive Congress during the government’s first months.

The government has attracted criticism for this failure from other legislators, including from the president of the Legislative Directory, Rodrigo Arias of the opposition PLN party, who said that the projects presented had been limited and of little relevance, wasting the usual opportunity for the executive branch to control the legislative agenda during the first three months of government. The administration’s political capital meant an opening to make decisions on urgent issues like macroeconomic policy, social investment and corruption—but it has been wasted. Even the 2023 national budget bill that must be approved by Congress in October has attracted criticism for including abrupt cuts in key government areas without the support of technical studies.

Clashes with the media

Chaves has repeatedly characterized the media as representatives of the powerful groups in the country that, during the campaign, he vowed to fight. This message, linking the press with “self-crowned feudal lords,” has allowed Chaves to normalize attacks against the media among some sectors of the population, despite the risks that this entails to press freedom and democracy.

In July, the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) issued a warning on the risks to freedom of expression and the press in the country, after the Ministry of Health suspended the operating permit for Parque Viva, the Grupo Nación-owned center. The government had argued that the park was generating traffic problems and that there were irregularities in its operating permits. The Constitutional Court also issued a warning to the administration, stating that it will not tolerate limitations on the work of the press or any type of censorship, after the communications minister allegedly ordered the administration to suspend all state advertising in specific media outlets and avoid granting interviews to them.

Five months is a small part of Chaves’s four-year mandate—and governing is a marathon, not a sprint. It remains to be seen how much Costa Ricans will continue to be satisfied with a government for its new way of doing politics, rather than its response to the population’s problems during a difficult economic scenario that affects the most vulnerable first, threatening to widen levels of inequality that are already among the highest in the region.

—

Benavides-Santos is a political scientist, researcher and international consultant. She is an affiliated researcher at Columbia University.