Since the pandemic, some workers around the world have embraced the trend of “quiet quitting”—in which they don’t actually abandon their jobs, but try to do the absolute minimum amount of work necessary to avoid negative attention.

The term came to mind during last week’s terrifying outbreak of drug-related violence in Ecuador, which saw gangs kidnap police and prison guards, invade a TV station and paralyze the business capital of Guayaquil. In response, conservative President Daniel Noboa vowed a crackdown, labeling the gangs “terrorist groups” and ordering the military to round up hundreds of suspected cartel leaders.

If Noboa stays the course, it would be something of a novelty. These days, several key Latin American countries including Mexico appear to be moving in the opposite direction—by quiet quitting the war on drugs.

Quiet quitting in the business world has been described as a way of coping with burnout, or a lack of commitment to the job’s core mission. It’s easy to understand why some regional leaders might be suffering from the same affliction, without—as the term suggests—being willing to say so publicly.

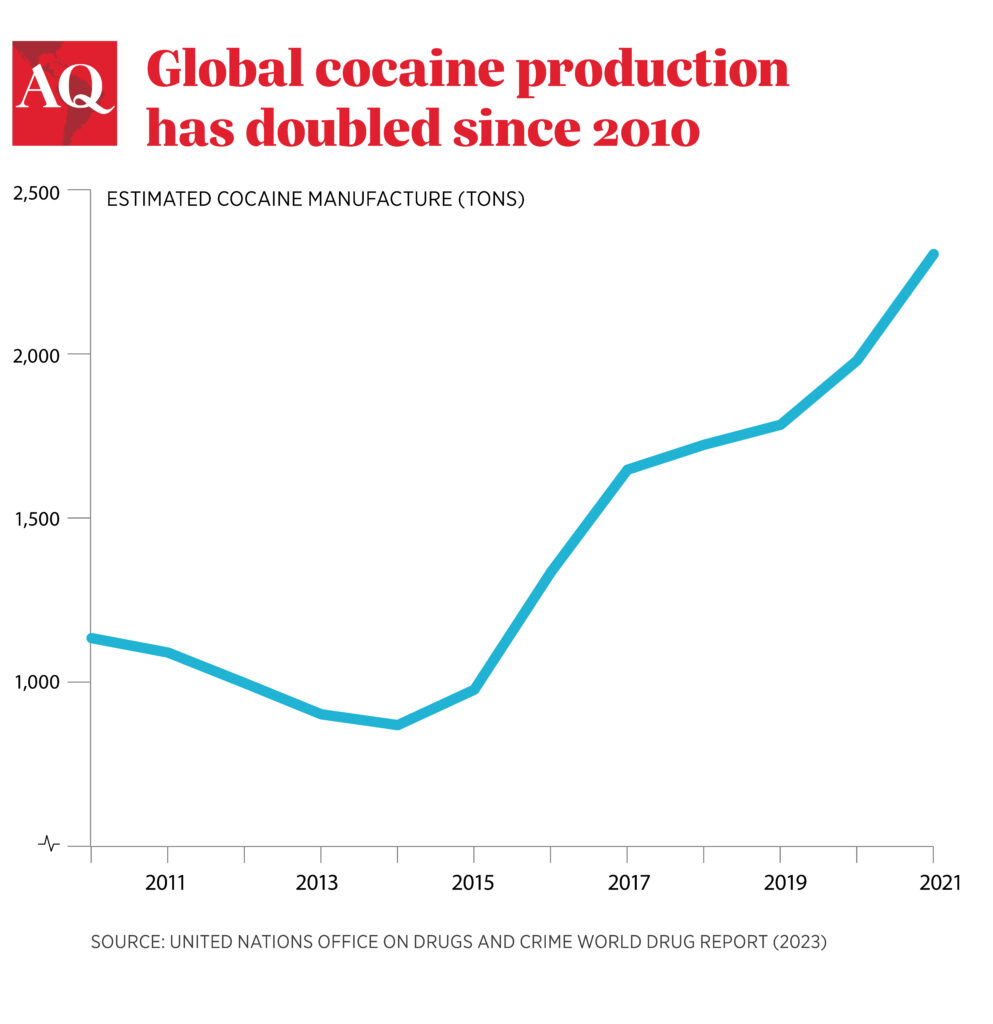

More than 50 years after Richard Nixon declared narcotics “public enemy number one,” and despite Plan Colombia, the Merida Initiative and other strong anti-drug initiatives by Latin American governments over many decades, both supply and demand have continued to reach new records. Global production of cocaine has doubled in the last decade, according to UN estimates. Nearly all the raw material is grown in just three countries, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia.

The profile of consumers has also evolved. While North America remains the leading market for cocaine, accounting for about 30% of global users, there are now about as many users within Latin America and the Caribbean (24% of the world total) as in Europe, the UN estimates. Asia (11%) and Africa (9%) have also seen rising demand.

Smuggling routes have shifted in response, helping explain why previously peaceful countries such as Ecuador, Chile and Uruguay have seen spikes in violence—as gangs battle each other, and sometimes governments, for control of ports and other territory.

Some governments, most notably Nayib Bukele’s El Salvador, have doubled down on the fight.

But several others, facing what they see as the futility of the drug war, yet unwilling to risk pariah status by forswearing it entirely, appear to be—quietly, sometimes subtly—backing off.

Listen to a conversation on Latin America’s security crisis on The Americas Quarterly Podcast

In Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador has shunned the tactics of his immediate predecessors, who confronted the cartels with unprecedented vigor starting in 2007—and saw Mexico’s homicide rate quadruple over the next decade, while drug flows did not decline in a lasting way. López Obrador has repeatedly described drugs as mainly a U.S. problem, one of “social decay,” and did not mention the issue at all in his latest State of the Union address.

While Mexico has continued to dutifully conduct some arrests and seizures, successive delegations of U.S. officials have visited in recent months to try to urge the government to take anti-drug efforts, especially on fentanyl, more seriously. A recent Reuters investigation found that, even when Mexico does raid drug labs, most are already abandoned—leading the influential Republican Senator Chuck Grassley to accuse López Obrador of conducting “an imaginary war on drugs.”

Some Mexican observers reach similar conclusions. “The president himself, with his rhetoric of ‘hugs not bullets,’ his courteous gestures with members of criminal families, and his allusions to the United States as the main interested party in combating some criminal organizations, seems to be sending a message that fighting crime is a subject far from his will,” wrote the prominent security analyst Eduardo Guererro in a recent column.

In Colombia, which produces about 60% of the world’s coca, President Gustavo Petro has said “the war on drugs was a failure,” and pushed other Latin American leaders at a summit in September to treat drug use mainly as a public health problem. While Petro’s government has continued some enforcement efforts, manual eradication of coca plants has fallen almost 80% in the past year, according to National Police data. Cultivation has jumped 65% since the pandemic began (under a prior government), reaching new record highs.

Elsewhere, one sees similar if not quite identical trends. In Bolivia, where coca growers are an important constituency of the ruling party, enforcement has long seemed half-hearted. Peru’s political volatility has undermined drug interdiction there, officials say. While Brazil’s government recently militarized security at some ports and airports, some officials privately say they are hoping not to disturb a tentative equilibrium between that country’s two main drug gangs. And of course Venezuela’s dictatorship abandoned the anti-drug fight years ago, allowing officials to get rich off of smuggling.

None of these strategies can be considered a panacea.

In López Obrador’s Mexico, the homicide rate has fallen slightly. But the cartels, apparently feeling less pressure, have dramatically expanded extortion, kidnapping and theft while buying off ever more politicians, Guerrero wrote. A similar dynamic can be found in São Paulo, South America’s biggest city, where the Primeiro Comando da Capital operates with considerable impunity: Homicide rates are among the continent’s lowest, but the gang controls vast swathes of the economy including illegal gold mining and logging in the Amazon, and kills anyone who gets in its way.

Still, it’s a balance many officials seem willing to pursue, believing it a better set of problems than the mayhem unleashed by direct confrontation.

The irony is that Ecuador’s latest crisis seems to have been presaged by a prior wave of quiet quitting. The government of Rafael Correa (2007-17) pursued an accommodative strategy with cartels as they dramatically expanded operations in the country, some observers say. When ensuing governments tried to arrest judges and police who had been co-opted by the gangs, the cartels lashed out—helping explain the violence last week.

Whether quiet quitting is really a novel trend, or just a new name for an old, cyclical behavior remains to be seen—in the workplace and in drug policy.

(With research by Emilie Sweigart)