Correction appended below.

ASUNCIÓN—Santiago Peña assumes Paraguay’s presidency on August 15 with a number of advantages, including a supportive Congress. But he faces also numerous challenges, as he tries to unite his party, manage the influence of his political mentor—businessman and former President Horacio Cartes—and handle international negotiations, from the Itaipú accord to U.S. sanctions against Paraguayan politicians.

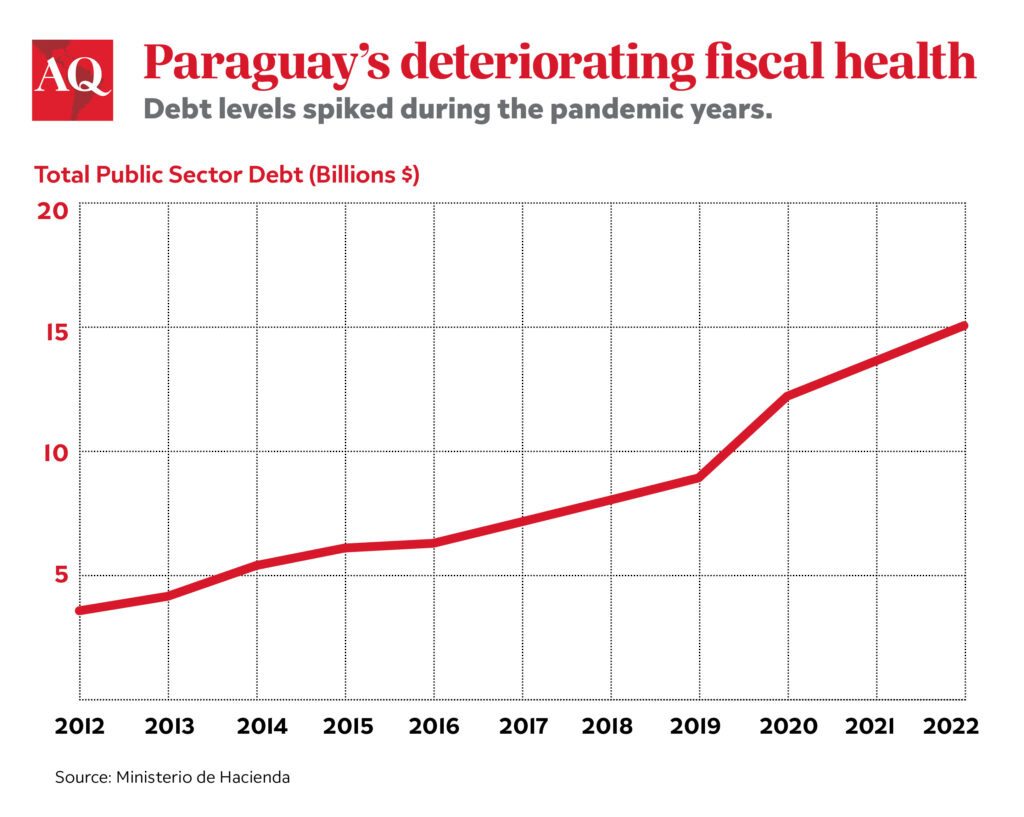

Paraguayans are concerned about unemployment, insecurity, corruption, infrastructure and healthcare—while the search for economic recovery from a 2022 contraction, driven in part by drought and a controlled but constantly increasing public debt, goes on.

To tackle these challenges Peña, who ran emphasizing his technocratic profile, wants to put his political capital to work reorganizing the Paraguayan state. Bolstered by a commanding victory of nearly 15 points in April’s elections, the incoming government enjoys robust support and holds majorities in both chambers of Congress.

Peña is so sure of his position that he has moved to set his plans in motion before even taking office. The new Congress, sitting since June, has set to work on two pivotal institutional overhauls. The first, already signed into law, unifies the National Customs Directorate and the Undersecretariat of State for Taxation (SET) into the National Tax Revenue Directorate. The second involves transforming the Ministry of Finance, previously led by Peña himself from 2015 to 2017, into a newly christened Ministry of Economy and Finance.

Peña has introduced a third, more contentious measure: the dissolution of the National Anti-Corruption Secretariat (SENAC), citing alleged inefficacy and the drive to optimize resource allocation. Detractors of this measure argue that rather than dismantling SENAC, it should be empowered with greater autonomy, resources and commitment. Some associate Peña’s move with the recent surge of corruption allegations targeting influential political figures in recent months.

Behind this confident barrage of legislation are underlying tensions that will test Peña’s political mettle. Despite the continued dominance of the Colorado Party, which has held sway with only one interruption since 1948, its unity is beginning to fracture amidst tensions between its two main factions. The primary faction, led by Cartes and aligned with Peña, is pitted against another faction characterized by diffuse centers of power prominently featuring current President Mario Abdo Benítez.

The battle lines were drawn between these two sides in a grievance submitted by former President Horacio Cartes to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Cartes argues he has been subjected to political persecution since the onset of Mario Abdo Benítez’s presidency. This legal action serves, too, as Cartes’ opportunity to distance himself from allegations levied against him by Brazil and the United States—Cartes contends these investigations are grounded in fabricated information supplied by the outgoing president.

This display of Horacio Cartes’ political influence sheds light on challenges for Peña: asserting himself as a political actor independent from his political patron. As Cartes’ political successor, the president-elect must demonstrate his capability to prioritize his own interests over those of others. This dynamic will play out both within his cabinet and in the inaugural actions of his administration.

Meanwhile, the opposition, fragmented by a substantial defeat, has yet to ascertain how to harness the sizeable portion of the population disenchanted with conventional politics and the absence of solutions. The primary opposition party, the Authentic Radical Liberal Party (PLRA), is embroiled in a fierce internal power struggle. The advocate for marginalized political voices, Payo Cubas, remains under house arrest due to his involvement in post-election unrest. Meanwhile, other parties grapple with the challenge of standing out against more dominant forces, either attempting reinvention or conceding ground.

Peña’s foreign policy challenges

On the international front, two major issues will concern Peña: the renegotiation of Annex C of the Itaipú dam treaty with Brazil and the forging of a new relationship with the United States.

After 50 years of the Itaipú treaty, this year a provision triggers talks to revise the framework for electricity provision. From 1984 to 2017, Paraguay provided Brazil with 85.7% of its energy at prices below market value. This energy powered Brazil’s southern, southeastern and central-western regions, especially São Paulo, a key industrial hub. But the arrangement resulted in estimated losses of around $77.3 billion for the Paraguayan state due to an initial agreement that placed Paraguay at a distinct disadvantage, and due to Paraguay’s inability to harness surplus energy for its own development.

Paraguay wants access to additional energy for projects such as electric transportation and clean-energy industrialization, and to attract investments and win better commercial terms for the energy surplus it supplies to Brazil. Lastly, Paraguay aims to lay the groundwork for expanding its energy sources and infrastructure. Brazil, meanwhile, will strive to safeguard its allocation of energy for industrial use and try to keep the right to buy Paraguay’s energy at a rate below market value. Talks will be tough, putting the Santiago Peña government to the test in its bid to level the playing field between the countries.

Meanwhile, tensions are emerging in the relationship between Paraguay and the United States. The overt insertion of the United States into Paraguay’s domestic political sphere through administrative and financial sanctions—for example, by designating Cartes and Vice President Hugo Adalberto Velázquez Moreno for “significant corruption” and applying Treasury sanctions in January to Cartes’s businesses—has provoked discord between these historically allied nations. Peña and his pick for foreign minister, Rubén Ramírez, want to preserve relations with the United States as a strategic partner—but they also want to curtail the United States’ sway over Paraguay’s internal affairs.

To this end, Peña has frequently emphasized his government’s commitment to its core alliance with the United States, Israel and Taiwan, while maintaining ongoing cooperation projects with the United States. However, he also promotes a discourse that emphasizes sovereignty and sees South America as the primary arena for international integration.

Santiago Peña’s new government begins its mandate with an advantageous position compared to preceding administrations. The Colorado Party’s majority will streamline the approval of numerous government initiatives. But this advantage also represents a major challenge. Ensuring control over his party and creating the essential scope for autonomous action, independent of the influence of his political mentor, Horacio Cartes, will be the hurdle most likely to persist throughout his tenure—and in this regard, regrettably, the odds seem to be against him.

This article was updated on August 10, at 12 pm EST, to correct a figure for estimated losses for the Paraguayan state from the Itaipu agreement with Brazil.