This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

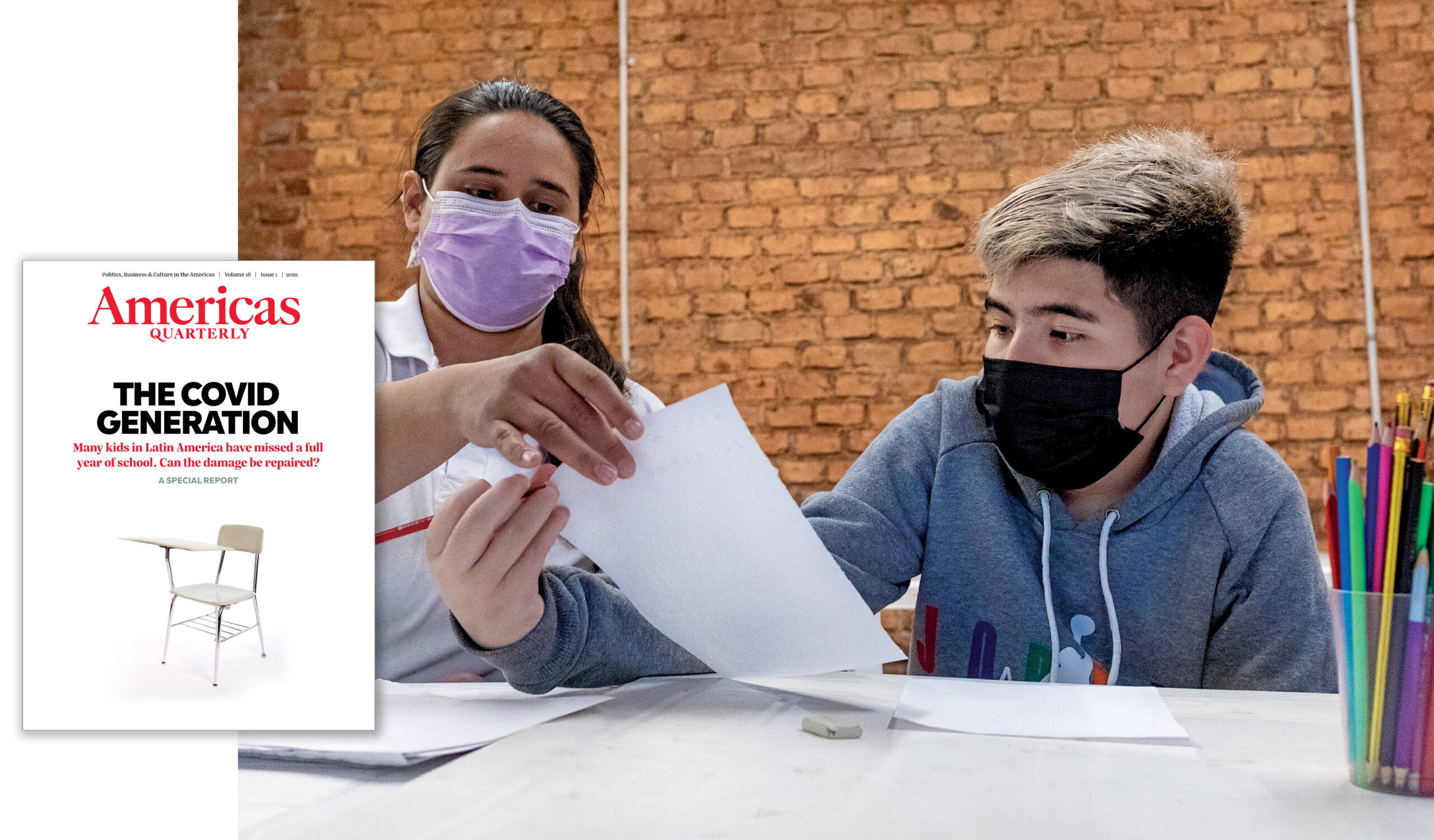

While there is awareness of the educational loss caused by the pandemic in Latin America, what was also lost was the opportunity to learn from the crisis. Much of the region’s progress in improving access to school over the last decade was undermined by the pandemic.

The crisis robbed many students of the opportunity to learn, while also causing them to lose skills they had already gained, pushing some children out of school.

The direct public health impact of COVID-19, its toll on human lives and the indirect impact on economic activity exacerbated inequalities in what was already the most unequal region in the world. The UN’s Human Development Report from 2022 that documented declining measures of life expectancy, education and income per capita since 2020—wiping out gains made between 2016 and 2019—shows that those declines were greatest in Latin America.

The suspension of in-person educational activities in Latin America was longer than in any other region, averaging 159 missed days of classes during 2020 alone, according to the World Bank. However, aggregate figures of school closures and attention to the approaches to educational continuity at the national level mask important variations within countries in how local governments and individual schools responded. For example, data from 10 Brazilian states (Alagoas, Amapá, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Maranhão, Pernambuco, Piauí and Sergipe) show that reading fluency of second graders decreased, while the percentage of children who did not even reach the most basic level—those considered pre-readers—increased from 35% in 2019 to 72% in 2021.

The inability to engage with and learn from remote education modalities caused some children to disengage from learning and to drop out. In Mexico’s Guanajato state, for example, the high school dropout rate increased from 11.6% in 2019 to 15.8% in 2020. Similarly, in the state of Querétaro, also in Mexico, high school dropout rates increased from 11.3% in 2019 to 15.7% in 2020.

In Latin America as a whole, 3 million students dropped out of school in 2020, or 1.7% of all students in the region, according to the Inter-American Development Bank. In contrast, in Uruguay, which had the shortest school closures and which had made considerable investments in digital education through the Plan Ceibal, the dropout rates in secondary education even decreased slightly during the pandemic and secondary school completion continued to improve.

It was not just deficient approaches to education and the compounding effects of the pandemic on income and health that limited the educational opportunities of poor children. It was also the differences in the responses of the various educational streams into which students are sorted. Poor children are often segregated into schools of low quality, which magnify the losses. In Chile, for instance, schools serving the most privileged students experienced the shortest closures. Across the region, governments and private education institutions created a variety of alternative ways to deliver instruction remotely.

To date, most studies of the educational impact of the pandemic have focused on national aggregate figures, missing out on the opportunity to learn from the important variations in policy responses within countries and the different results they achieved. We are missing out on the opportunity to understand the mechanisms that underlie the increases in educational inequality that the pandemic has produced. For instance, the municipality of Sobral, in Pernambuco, Brazil, had experienced considerable learning gains over the last two decades.

In 2019 most students in the first two grades of elementary instruction were reading at grade level. For first graders, 91% could decode, 80% could understand and 71% could read fluently. For second graders, 90% could understand and 84% read fluently. Two years later, in 2021, those figures had dropped precipitously. Among first graders, only 49% could decode, 22% could understand and 18% were fluent. Among second graders, 60% could understand and 51% were fluent. In another study, though, two other municipal networks (Coruripe in Alagoas, and Machados in Pernambuco) showed much higher levels of fluency than the average in their states. The likely reason is that both towns had, before the pandemic, implemented data-based, formative professional guidance for teachers to improve literacy instruction.

The effect of the pandemic on education is not a single story, but several different experiences, largely mediated by nationality and social class. And COVID-19 proved to be a quintessential “Matthew effect,” a term coined by sociologist Robert Merton drawing on the parable of the talents: how unequal initial conditions often compound inequalities.

—

Reimers is the Ford Foundation professor of the practice of international education at Harvard University, where he directs the Global Education Innovation Initiative. Since 2020 he and his colleagues have been studying the educational impact of the pandemic and options to rebuild educational opportunity.