This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the education crisis | Leer en español | Ler em português

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted education systems worldwide, but the challenges in Latin America have been particularly acute. Policy choices across the region led to the longest average school closures of anywhere in the world. But when classrooms finally reopened, parents’ mistrust of government stopped many from sending their children back. Meanwhile, limited Internet connectivity and lagging digital skills made alternative forms of learning perhaps even less effective in Latin America than they were elsewhere. All told, access to education and enrollment rates in the region could be set back 10 years or more as a result of the pandemic – with grave consequences for economic growth, political stability, democratic governance and efforts to reduce poverty and inequality. Not since the “lost decade” of the 1980s has Latin American education faced such a profound threat.

There are three paths that governments, civil society, parents and teachers can take in response. If they learn from the past, and choose wisely, the pandemic could be a springboard to remake Latin American education better than it was before. Choose the wrong path, however, and the stagnation and learning losses of the 1980s are sure to return – and worsen. The good news is that many in the region have already shown a way forward. From Brazil to Mexico, local governments, universities and the private sector have faced COVID-19 with collaboration and fresh ideas. But a truly better future will take an even larger dose of ambition.

Catching up

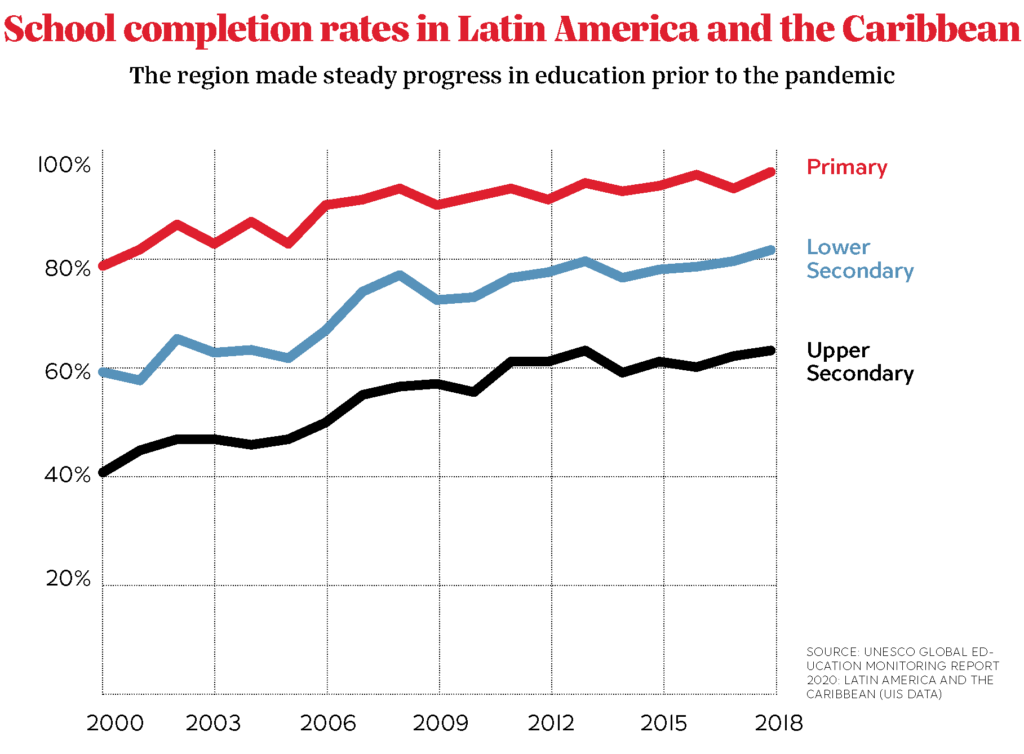

To understand where Latin American education needs to go, it helps to first understand how far it’s come since the 1980s, when budget cuts in response to the region’s debt crises led to stagnation in enrollment rates and student achievement. Not surprisingly, these effects were most keenly felt by lower-income families, as inequities in education spending deepened and students without access to private education fell further behind. In response, governments in the region supported reforms that produced visible gains, including increases in compulsory education requirements, which led to a significant increase in schooling levels across the region. By 2020, Latin America enjoyed almost universal enrollment for primary and lower secondary school. Overall the number of children out of school fell from 15 million in 2000 to 12 million in 2018, according to UNESCO. In that time, the share of students who completed primary education rose from 79% to 95%, while lower secondary education completion rose from 59% to 81% and upper secondary education completion in-creased from 42% to 63%, all above global averages.

Despite these advances, significant gaps remain. One in three children between the ages of four and five in the region does not attend preschool. Only four out of five stay enrolled between the ages of 13 and 17, and 14% of students that age are still in primary school as a result of chronic repetition. Educational opportunities remain stratified by socioeconomic status: More than half of children from low-income families in rural areas fail to complete nine years of basic education. Overall, half of Latin American students fall below minimum reading literacy rates by the time they’re 15, according to OECD assessments. COVID-19 has exacerbated these issues – and now threatens to reverse recent gains.

Three ways forward, one big opportunity

Paradoxically, the current crisis could encourage a cycle of reforms to tackle these challenges, and make education more inclusive and more relevant to the needs of a changing, complicated world. This will only happen, however, if stakeholders on all sides of the equation take the right approach. Their options are denial, retrenchment or ambition.

The first of these would be the worst. Policymakers in the denial camp might think their job is done once schools are fully reopened. But this would ignore the profound effects that two years of a pandemic have already had on education systems: learning loss, disengagement, student dropout, teacher burnout, and a growing lack of trust among the public, education authorities and governments.

This is especially true for students from lower-income families, where limitations on home-learning have been compounded by the health, economic and social effects of the pandemic. Internet connectivity and the digital skills divide between high-income students and teachers and their lower-income peers offer prime examples. While overall 77% of 15-year-olds in Latin America have Internet at home, the figure is just 45% for students from the lowest-income quintile, according to the World Bank.

Retrenchment, meanwhile, would perceive of the status quo as a worthy goal. It would aim to recover pandemic-related learning losses and enrollment rates, perhaps through a combination of added school hours and hybrid learning, though driven by awareness of new fiscal constraints. But prior to the pandemic, 30% of employers in Latin America blamed a poorly educated labor force as a serious constraint to productivity, compared to 20% worldwide. Why simply try to return to the way things were?

By contrast, an ambitious mindset would aim to build back better. The goal would be nothing less than a renaissance in education, to prepare students with the skills they need to improve their circumstances and those of their communities well into the future.

Such a rebirth of Latin American education would rest on the pursuit of three simultaneous goals: improving the effectiveness of education while the current pandemic persists, recovering and rebuilding educational opportunities post-pandemic, and making education systems more resilient to future disruptions and better equipped to prepare students.

Achieving these goals will first require a full diagnosis of how the educational context has changed with the pandemic. Educators and governments will need to develop new teaching strategies that can both respond to those changes and be adapted to future outbreaks. Finally, Latin American countries need to improve the capacities of teachers, administrators, students, families and education systems writ large. Coherence and alignment among these goals and the policy response will be critical, bringing together all sides of the education equation to pursue common strategies. A fragmented or siloed approach – one in which teachers are taught how to use digital platforms but household connectivity remains unchanged, for example – won’t be enough. Nor will simply trying to make up lost ground by adding to already overburdened curricula. Instead, learning plans need to be accelerated and reprioritized. This may sound utopian, but there are already signs that such ambitious change is taking place.

Opportunity in crisis

In a recent study, my colleagues and I identified a range of education innovations developed during the pandemic. Many of these were aligned with an ambitious vision for the future of education recently proposed by an international UNESCO commission.

In Brazil, for example, a lack of national education leadership led state governments and civil society organizations to generate their own approaches to teaching during the pandemic. These included the creation, in record time, of a learning program in the state of São Paulo to sustain education through a variety of delivery systems. An online platform to support learning and student assessment was supplemented with television, radio, WhatsApp and printed learning packages. Crucially, this came alongside programs to help teachers and school principals improve their own skills as well. The project was the result of unprecedented collaboration among the state government, the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, and the support of several state business leaders and companies.

Meanwhile, state governments in Mexico developed improvements to a national TV education program. Officials in Guanajuato, for instance, developed an online program of interactive home study guides and provided regular, real-time feedback to students.

In Colombia, the International Rescue Committee developed audio-based education materials to address Venezuelan refugee students’ social and emotional learning needs, a facet of education that was highly disrupted by the pandemic. Also in Colombia, Alianza Educativa, a non-profit organization that runs 11 charter schools in Bogotá, turned its traditional social and emotional learning curricula into a schoolwide strategy for children and their families in vulnerable communities.

The list goes on: an assessment of teachers’ digital skills in Costa Rica, an open-source platform to improve teacher training in Guatemala, an online development program for teachers in rural Peru. The common denominator in all these programs was partnership: institutional innovations as the result of new collaborations or the expansion of existing ones. This trend was true throughout the region. Universities in Latin America, especially, showed commitment to the common good, supporting public schools during the pandemic in ways that could well have lasting effects on how these institutions define their missions in the future.

In Chile, for instance, President Sebastián Piñera called on the rectors of the Universidad de Chile and the Pontificia Universidad Católica to join together to help the government develop a range of policy responses to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. The Catholic University helped public school systems reprioritize their curricula, with a focus on helping teachers understand and expand their role in supporting social and emotional development for students.

The variety of examples suggests that an education renaissance may look different from country to country. But a framework exists. COVID-19 led to one of the most serious crises in the history of education in Latin America. But it has also created new partnerships between public and private actors and produced unprecedented innovations. Maintaining the priority on improving education, sustaining collective leadership and deepening innovation would help restore faith not just in education institutions, but also in government, democratic rule and, most of all, a better future.