As bad as life has been for Venezuelans over the past decade, it could have been worse. For all the suffering, the repression of political dissidents, the exodus of a quarter of the population and other horrendous acts, it was still a country where—unlike Cuba and Nicaragua—political speech was not completely restricted, and some trappings of democracy were maintained, apparently because Nicolás Maduro and his backers cared at least somewhat about global opinion and maintaining economic linkages to their neighbors and other Western democracies.

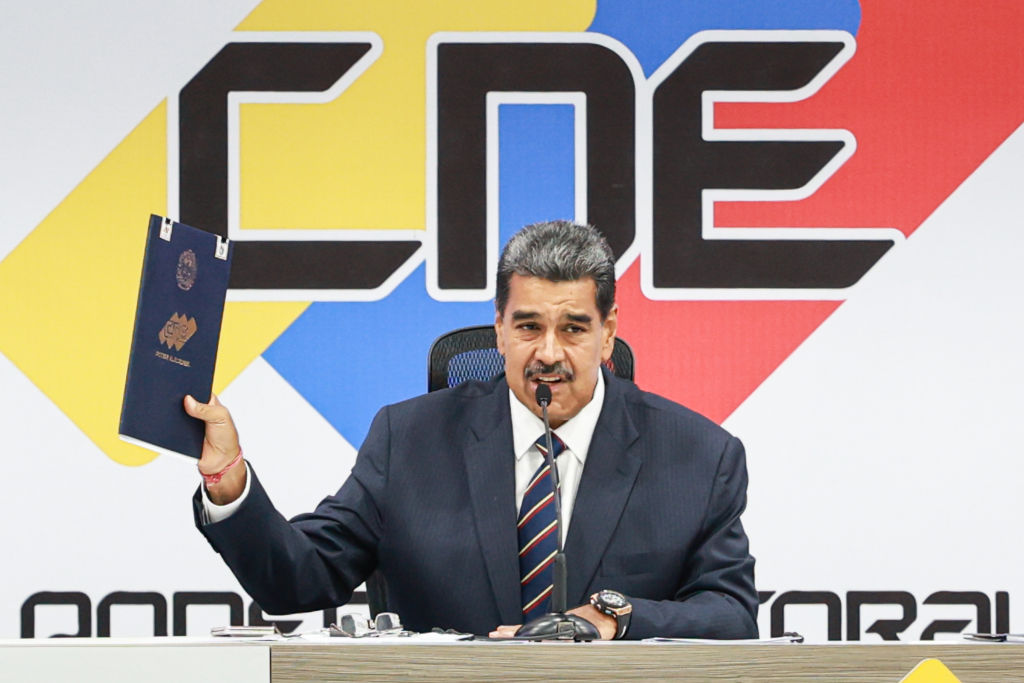

This desire, this reluctance to go “full Ortega,” in the mold of Nicaragua’s dictator Daniel, seems to have led Maduro to a miscalculation he now surely regrets: Allowing Sunday’s presidential election to take place as it did. Even though voting was never going to be free or fair, Maduro did ultimately, under pressure from the United States but also his longtime leftist supporters in Brazil and Colombia, allow for the participation of Edmundo González, a candidate aligned with the popular opposition figure María Corina Machado. Maduro vastly underestimated Machado’s political skill, while his prohibition of European and most other credible election observers was in the end not enough to blind the world, or his own people, to the nakedly obvious election fraud his government announced on Sunday night.

As Monday progressed, it became clear that Maduro was willing to take the next step—and become a fully rogue, isolated, Nicaragua-style regime if necessary to retain power. The regime named Machado as a suspect in so-called electoral sabotage, a potential prelude to arresting her and other opposition figures. After several Latin American countries called for Maduro to respect the popular will, Maduro reacted by ejecting all their diplomats from Caracas—an extreme step even the Cubans have hesitated to take over the years. He suspended many of the few remaining international flights into his country. And as thousands of Venezuelans streamed into the streets late Monday and into Tuesday to demand their vote be respected, toppling several statues of the late Hugo Chávez, there were fears of a crackdown even more violent than previous rounds of repression in the 2010s which left hundreds dead.

In trying to understand Maduro’s behavior, and anticipate what may happen next, I come back to two key assumptions. The first is that what Maduro and his allies fear most is not losing power per se, but spending the rest of their lives in a Supermax federal prison in the United States. With numerous officials including Maduro facing indictments in U.S. courts on drug trafficking charges, and enough documented corruption and human rights abuses to keep The Hague fully occupied for a decade, Maduro and his backers in the Venezuelan military were never going to leave office without some kind of sweeping deal for immunity and/or transitional justice. The second assumption is that Chavismo’s model has always been Cuba, where authorities have “successfully” stayed in power by repressing dissent, ignoring the economy when necessary and exporting malcontents for 65 years and counting. Take the long view, the Havana view, and this is just another storm that will pass.

It is possible these assumptions are wrong: The Venezuelan power structure may be weaker, more divided and eager for change than we appreciate, believing their growing lack of legitimacy at home and abroad to be unsustainable. Maduro may be staking out tough ground now in anticipation of an eventual negotiation. But if Maduro is indeed willing to do whatever it takes to stay in power, then whatever path remains to a democratic transition will be both narrow and extremely dangerous in the days ahead.

International pressure, particularly from Brazil and Colombia, will be necessary—but insufficient. At this stage, Maduro’s regime knows that the world knows that it lied about Sunday’s results, and it simply does not care. The threat from Washington or European nations of further sanctions, or recognizing González as Venezuela’s legitimate leader, also seems unlikely to move the needle; we’ve been there already, with little positive effect and plenty of collateral damage. Critically, Maduro received instant support on Monday from the governments of China, Russia and Iran, which may provide enough of an economic and diplomatic lifeline for him to weather whatever storm is coming (but may lead Latin America’s democrats to ask renewed questions about those countries’ true interests and impact on the region).

The focus, then, turns to dynamics within Venezuela itself, many of them unknowable: How willing will everyday Venezuelans be to risk injury or death to attempt to force Maduro from power? Can Machado and González keep their supporters, many of whom are understandably disillusioned by numerous cycles of hope and repression over many years, engaged over time? Can they do so while simultaneously keeping channels open with elements within the state apparatus in order to negotiate some kind of transition? Will the security forces, which so far seem united and capable of suppressing any dissent in their ranks and in society at-large, begin to fracture if the show of popular resistance is massive enough? How willing will rank-and-file soldiers be to spill their countrymen’s blood?

These are the questions that dissidents in Nicaragua, Cuba, China, Russia, Romania, Libya and elsewhere have faced over the years. The results have mostly been grim, pointing once again to that old adage: Once dictators take power, they are almost impossible to remove. Almost.