Ilan Goldfajn, elected president of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) last Sunday, has a low public profile but a reputation for competence. He has held positions in the public and private sectors, led Brazil’s Central Bank, and was director of the International Monetary Fund’s Western Hemisphere Department. Now, his reputation will be put to the test as the IDB navigates formidable internal and external challenges.

Many of his peers say he has what it takes. “He is a rare almost-unanimity in the profession,” said Adriana Dupita, an economist at Bloomberg Intelligence. Marcelo Neri, founder of the Center for Social Policy at Fundação Getúlio Vargas, said Goldfajn’s uncommon combination of high-level experience in academia, international organizations, and the private and public sectors made him “an exceptional choice.”

But when Goldfajn takes office on December 19, he will need to restore the morale of an institution buffeted by the firing of former head Mauricio Claver-Carone after an investigation into misconduct, all while tacking against gale-force global economic headwinds and advancing a difficult but promising reform agenda seeking to bring modernization and growth to the institution.

A history of competence

Goldfajn was Brazil’s nominee to lead the IDB and will be the first Brazilian to hold the position. During the selection process, he was considered the favorite all along even though four other member nations also put forth candidates, in part because he has such a good reputation among fellow economists.

Before working with the IMF, Goldfajn led Brazil’s Central Bank from 2016 to 2019, an especially tumultuous time for the country. Nominated by then-President Michel Temer—who had just been given the reins to the country during Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment process—Goldfajn faced a deep economic crisis that saw Brazil’s GDP fall by 3.5% in 2015 and 3.3% in 2016.

“He kept his calm and cautious stance while the country was in upheaval in 2018 due to a national trucker strike,” said Dupita, “despite markets claiming for an interest rate hike, and later for cuts before it was time.” While he was at the helm of the Central Bank, inflation in Brazil fell steeply. From the end of 2015 to the end of 2018, inflation declined from 10.67% to 3.75%.

In his role as director of the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department, which he will leave to head the IDB, Goldfajn tackled the region as a whole, as well as the latest negotiations over the debt of Argentina, holder of the largest loan the Fund has ever made. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva credited Goldfajn as “instrumental” in the development of climate change-specific programs for the region. He is expected to continue to focus on climate in his new role.

That same experience drew criticism from other quarters. Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador called the IDB’s choice of Goldfajn “more of the same that has been applied during the whole neoliberal period.” Ricardo Carneiro, writing for the left-wing Brazilian paper Carta Capital, argued of the selection process that it “causes discomfort among the countries in the region that an IMF staff director … could ask these same countries for votes for his election at the IDB,” implying Goldfajn could retaliate against governments opposed to his bid.

During the selection process, there was initially some doubt about whether the transition team of Brazil’s President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva would try to sabotage Goldfajn’s candidacy, which had been presented by outgoing President Jair Bolsonaro’s economy minister. Former Finance Minister Guido Mantega—a member of Lula’s transition team who has since resigned—asked the IDB to postpone the election. However, Lula’s international advisor, Celso Amorim, later said the president-elect did not have a view on Goldfajn’s candidacy either way. For Arturo Porzecanski, a research fellow at American University, this was “crucial to the outcome” of the November 20 IDB selection. Goldfajn was elected by a large majority of the vote from the Bank’s Board of Governors, which includes representatives from its 48 member nations.

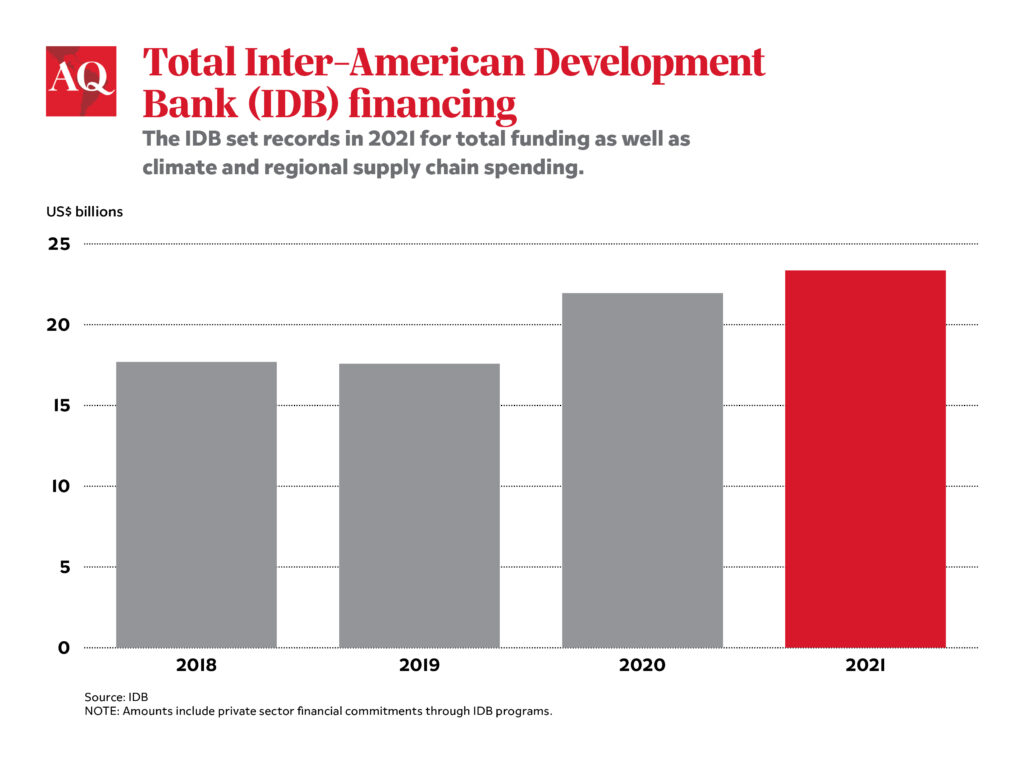

In 2021, the Bank and IDB Invest, its private sector arm, set a series of promising records. They arranged a record $23.4 billion worth of financing for Latin America and the Caribbean, up from $17.6 billion in 2019. This figure included three other record numbers—$3 billion in mobilized private financing; $2.3 billion to shore up regional supply chains; and $4.5 billion for climate-related projects. Meanwhile, the 2022 Aid Transparency Index ranked the IDB third among 50 major aid and development organizations, giving it high marks in all five areas of evaluation.

Challenges ahead

Earlier this year, the institution’s leadership approved a roadmap for reform and modernization. This internal modernization seeks to reduce bureaucracy and risk-aversion so the IDB can focus on de-risking private sector investment, establishing new equity investment policies, and deploying new financial and technical tools to help crowd-in private funding. The Bank also aims to introduce major new climate instruments and rapid disbursement facilities.

To help the region confront a daunting global environment marked by the consequences of inflation, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the IDB’s leadership also mandated a proposal for a capital increase, and promised that IDB Invest—which as of March managed a portfolio of $14.8 billion—would become more active.

Yet morale seemed to be flagging under the strain of reform as the institution began to fall behind on its timetables. Then it hit a low point when Mauricio Claver-Carone was investigated for failing to disclose a conflict of interest involving a romantic relationship with a subordinate. The Board of Governors voted to fire him in September.

Adding to the drama, the practices of multilateral lenders like the IDB emerged as a central issue at the recent COP27 climate talks in Egypt. Various leaders and delegations called on multilateral lenders to help avert the worst consequences of climate change by more closely aligning financing with their own stated climate goals. The need for climate-related reform in international financial institutions even made it into the final agreement inked at the summit.

Now, it falls to Goldfajn to restore the reputation of the Bank’s presidency and guide the institution through a period of global economic turmoil as well as an internal process of growth and modernization.

During the selection process, Goldfajn said, “The IDB should be less ideological [and] more technical.” He promised to focus on issues like inequality, climate, the energy sector’s transition to renewables, and improving the region’s physical and digital infrastructure to boost investment.

“Now migrating to financing long-term projects at the development bank, [Goldfajn] will be able to combine his views on the need for initiatives that can impact society,” Dupita said, “and acknowledge the macroeconomic reality of recipient countries.”

Otaviano Canuto, a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South who has held posts at the World Bank and the IMF, said Goldfajn would indeed seek to ensure that “the IDB can support Latin America and the Caribbean in the current global context as a provider of accessible, reliable and green energy, in addition to contributing to regional and international food security.”

“I like the vision that Ilan proposes for the IDB,” he said.

—

Brown is editor and production manager at AQ.

Tornaghi is managing editor at AQ.