This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on transnational organized crime | Ler em português | Leer en español

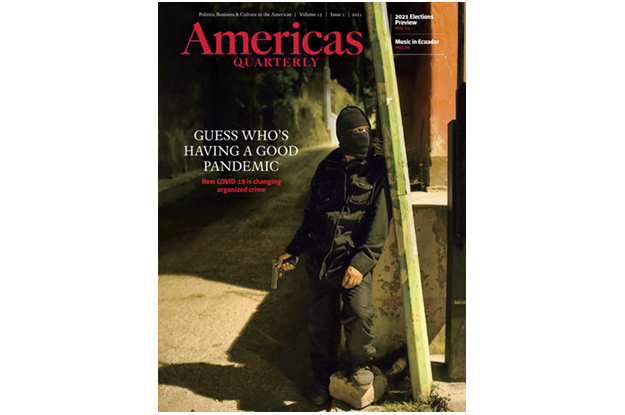

Along with Netflix, food delivery services and toilet paper manufacturers, the list of businesses bolstered by COVID-19 also includes organized crime groups. Gangs like the Brazil-based First Command of the Capital (PCC, by its Portuguese initials) and Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel are taking advantage of distracted governments and desperate populations to tighten their grip over swathes of the economy, political structures and, often, territory as well.

The tale of cartels getting rich off drug trafficking in the Americas is not a new one — it’s at least 40 years old and, while names and faces change, it’s depressingly constant in its themes of unwavering supply and demand (which still comes mainly from the United States). But there are signs the pandemic really may be a game-changer, creating long-term headaches for governments everywhere, including the new Joe Biden administration.

Criminal groups thrive best in areas where residents see them as a more effective and caring version of the state. As the virus spread, it was often gangs who enforced lockdowns in Mexico, distributed food in El Salvador and imposed curfews in Rio de Janeiro. They have trafficked in pandemic paraphernalia like surgical masks, test kits and sanitizer. Some expect they will try to control distribution of vaccines.

COVID-19 also caused a spike in unemployment, adding to the more than 20 million young Latin Americans who neither studied nor worked on the eve of the pandemic. After the region’s economies shrank 8% on average in 2020, most forecasts expect only a 3.5% recovery this year — meaning misery will persist. That has proven fertile recruitment ground for gangs in Colombia, and probably elsewhere. With fewer people on the streets, some gangs have diversified further into digital crime.

It’s a sobering picture, and though we consider ourselves optimists at AQ, this is one area where we frankly see little chance of major change. Under Biden and a split U.S. Congress, a wholesale rethinking of the “war on drugs” seems unlikely. Some governments don’t seem to see fighting organized crime as a top priority. Others such as Venezuela meet the definition of a narco-state. The rest are simply overwhelmed.

In that light, the focus should probably be on managing the consequences. That means better coordination among the hemisphere’s governments and militaries, as well as following the example of Brazilian police, who have cracked down on the PCC’s money laundering. Economic measures to attenuate rising inequality might also help. These steps are more Band-Aid than cure — but in the age of COVID-19, that may be all we can expect.