This article is part of AQ’s special report on sustainable development of the Amazon | Ler em português | Leer en español

Half a century ago, during Brazil’s military dictatorship of the 1960s and ’70s, magazines burst with propaganda portraying the Amazon as a “Green Hell” to be conquered at all costs. “Here, we defeated the forest!” boasted one ad showing bulldozers and fallen trees. In the decades since, an area bigger than Texas and Pennsylvania combined has been razed, reducing the forest’s area by some 20%, mostly to make room for cattle ranches, soy farms and illegal mines.

Today, we know this was a disastrous growth model for the planet – but also for the 35 million people who live in the Amazon basin, which includes parts of eight countries. Whatever profits came from destroying the forest went to a miniscule number of ranchers and companies. In the Brazilian Amazon, residents have incomes 40% lower than the national average, while suffering higher rates of unemployment and health issues. Meanwhile, a resurgence of the slash and burn model under President Jair Bolsonaro, a former Army captain still enamored by some of the former dictatorship’s ill-advised ideas, has put Brazil’s entire economy at risk of consumer boycotts and sanctions from a world no longer willing to tolerate such devastation.

The good news is that another model is possible; One in which the standing Amazon forest is treated as a one-of-a-kind, priceless economic asset, rather than an obstacle to progress. Recent technological advances, as well as changing global consumer preferences, point to a future in which Brazil and other countries could become green superpowers, harnessing the Amazon’s natural wealth to export everything from sustainably cultivated cocoa, açai and fish to promising new inputs for cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Such business, if managed the right way, could generate millions of green jobs inside and outside the region.

The idea of sustainable development tends to generate skepticism, and with good reason. Bolsonaro’s recent embrace of the concept feels to many like a cynical diversionary tactic. Others worry about “greenwashing” by corporations. But simply building a fence around the Amazon will not work. After progress in the 2000s, deforestation rates started to rise again in 2012, just as Brazil’s economy began its current struggles, and have doubled since then. It is clear that poverty, along with corruption and organized crime, must be addressed to help keep the Amazon intact.

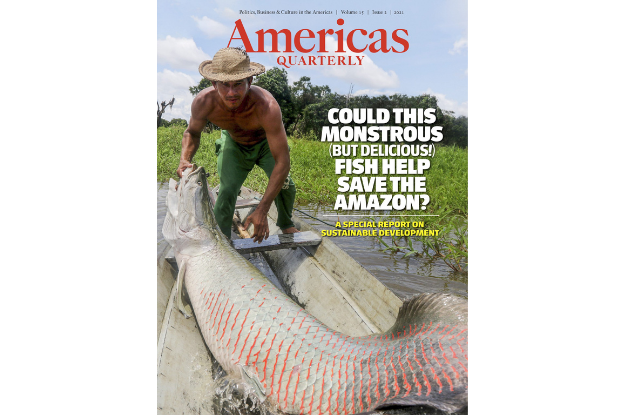

Going forward, governments, companies and civil society should work together to help build a virtuous circle – in which Amazon communities see the value of the forest, work to preserve it, and benefit directly from its bounty. In this issue, we highlight several cases where this is already happening. Our cover story looks at the pirarucu, a monstrous 450-pound fish that will never win a beauty contest, but has a delicious white flesh that gourmets find irresistible. Other case studies range from coffee to highly regulated mining to jaborandi, a once-endangered Amazon shrub that is used in eyedrops for glaucoma.

There is much work to be done to make this vision a reality: Global consumers will never pay a premium for Amazon products as long as deforestation continues — it must fall to zero as quickly as possible. Governments need to resolve the poor logistics, high taxes and other challenges that make doing business in the region so difficult. Some Wall Street investment funds complain they can’t find nearly enough viable businesses capable of achieving scale.

But there is a list of powerful reasons to keep pushing, including the quest for social and racial justice in a region where more than 80% of residents come from historically marginalized Black and Brown communities. Speaking before the US Congress in April, President Joe Biden said the key to dealing with the global climate crisis is “jobs, jobs, jobs.” Under the right conditions, it could be a strategy for saving the Amazon, too.