The election to succeed President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2024 is already receiving blanket media coverage in Mexico and beyond. But another contest, for Mexico City’s mayor, is also grabbing headlines, as early signs suggest it could lead to a nationally relevant shift in control of the megacity of 9 million.

The position of Mexico City mayor “has always been historically the second-most important political position in the country,” Eugene Zapata Garesché, global director for strategic partnerships and head of Latin America and the Caribbean at the Resilient Cities Network, told AQ. “Being mayor of Mexico City is like being a head of state”.

Indeed, the position has been a platform for many politicians with bigger ambitions: López Obrador is a former Mexico City mayor, as is Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard. Both Ebrard and Claudia Sheinbaum, the city’s current mayor, are current presidential candidates within the ruling Morena party.

The city’s population and budget exceed those of some nations. According to INEGI, the national statistics agency, Mexico City accounted for 15.8% of Mexico’s GDP in 2020. The 2023 budget for Mexico City is $13.5 billion, and a 2020 government survey counted over 90,000 public security officials in the capital. Zapata commented that the city’s budget is “bigger than the budget of many countries in the world” and the “police force is bigger than the armed forces in many countries.”

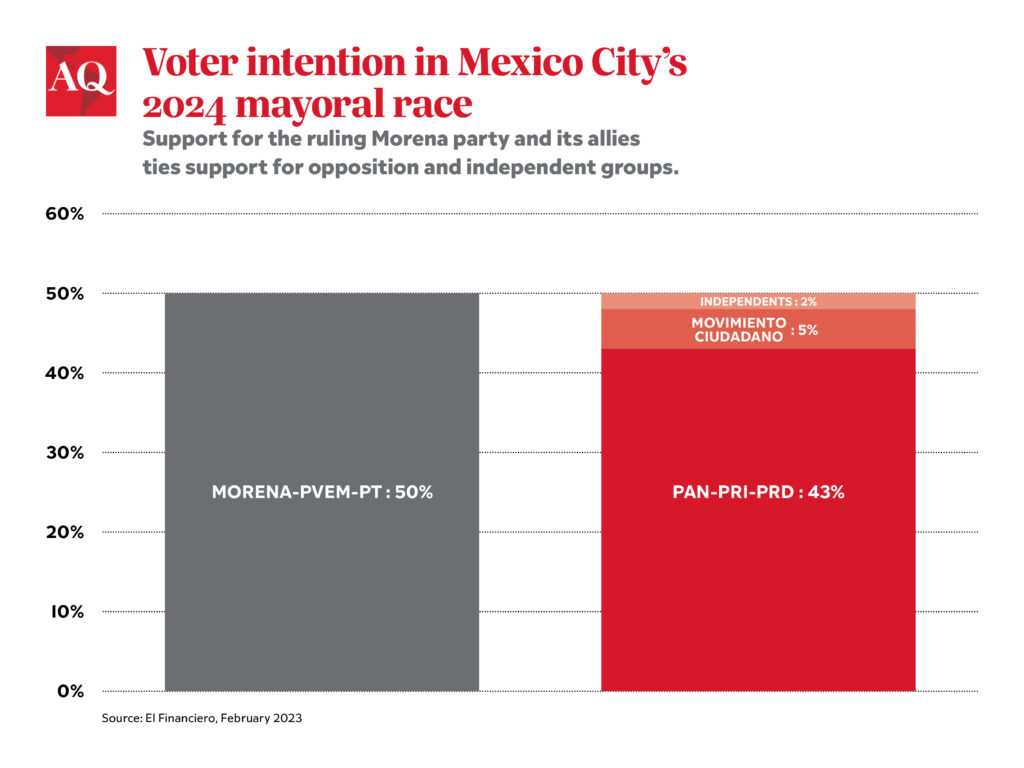

And that’s why a potential shift in control is generating so much attention. Recent polling suggests that the opposition, though fragmented, could have a chance of winning in Mexico City in 2024. Opposition politicians already gained control of half of the city’s districts in the June 2021 midterm elections, fueled by voters’ dissatisfaction with the ruling party’s pandemic management, economic losses, and problems with the capital’s infrastructure, most notably the May 2021 metro overpass collapse that killed 26 people.

Traditionally, the processes of fielding mayoral and presidential candidates are closely aligned. According to Luis Rubio, president of México Evalúa, “since the 90s, some 89% of Mexicans pick the candidate for the presidency and vote straight down for them in every other election for the same party.” Rubio told AQ “the importance of Mexico City is to align the two candidates because one helps the other.” Zapata noted that “the election for Mexico City government will be part of the presidential election. This is not going to be an independent situation.”

An opening for the opposition?

Since 1997, Mexico City has been governed by two left-leaning parties: the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) or Morena (the party founded by López Obrador). But that tradition may be threatened by problems in the city’s aging metro system, which have continued since the 2021 tragedy. In January, a collision led to one death and left over 100 people wounded. Sheinbaum decried sabotage, and last month her administration deployed over 6,000 members of the national guard in the metro system.

Longstanding dissatisfaction with the quality of other public services, especially water management, may cause voters to shift their support away from Morena. Feminist movements have expressed their frustration with the government’s inaction amid increasing femicides and violence against women. In recent years, massive demonstrations have been held in Mexico City, and protests are expected in the capital in March.

The opposition has sensed an opening. Alejandra Soto, associate director at Control Risks, noted that “as the presidential election draws near, there are a lot of incentives by Sheinbaum’s political rivals to shine a light on everything that’s not going well in the city.”

The opposition Va por México bloc, which includes the PAN, PRI and PRD, offers several potential candidates. They include Senators Xóchitl Gálvez and Kenia López Rabadán, as well as Mexico City district mayors Santiago Taboada and Lía Limón. Many observers see Gálvez, a former leader of the capital’s Miguel Hidalgo district who has emphasized Indigenous rights, as a leading contender.

On the Morena side, possible candidates include Iztapalapa Mayor Clara Brugada, Secretary for Security and Citizen Protection Rosa Icela Rodríguez, party president Mario Delgado and Secretary of the Mexico City government Martí Batres. Brugada is a popular, security-focused mayor of a district of 1.8 million people in eastern Mexico City, and has taken an early lead in polling.

National congressman Salomón Chertorivski, who hails from the progressive party Movimiento Ciudadano (MC), has also thrown his hat into the ring. His party has so far resisted attempts by Va por México to join their coalition. Though it is small, Rubio described MC as a “relevant player not only in Mexico City, but in general.” If MC goes into the election on its own rather than as part of the coalition, the party could siphon votes from both the opposition and Morena.

Mexico City tends to be more progressive than the rest of the country, but Soto told AQ that it is “more likely than ever before that we’ll have alternation (of power) in Mexico City. The chances of the opposition will be more even now than they have ever been in the city, which is usually not drawn to a right-wing agenda.” Still, Soto cautioned that “it will not be an easy win in Mexico City, because there are interesting candidates from Morena and in the opposition.”

Beyond 2024, the future leader of the capital, like López Obrador, may also aspire to the nation’s highest office. As Zapata noted, “Mexico City is the waiting room for the presidency today more than ever.”