After a contentious selection process, Morena is set to name its candidate for Mexico City mayor on November 10, and the battle between Clara Brugada and Omar García Harfuch could be the first significant test to reveal Claudia Sheinbaum’s influence within the ruling party. Either of the two would be in a strong position to win what is considered both the second-most important elected office in the country and a launching pad to the presidency. That means the candidate announcement will not only shape next year’s presidential election, but national politics for years to come.

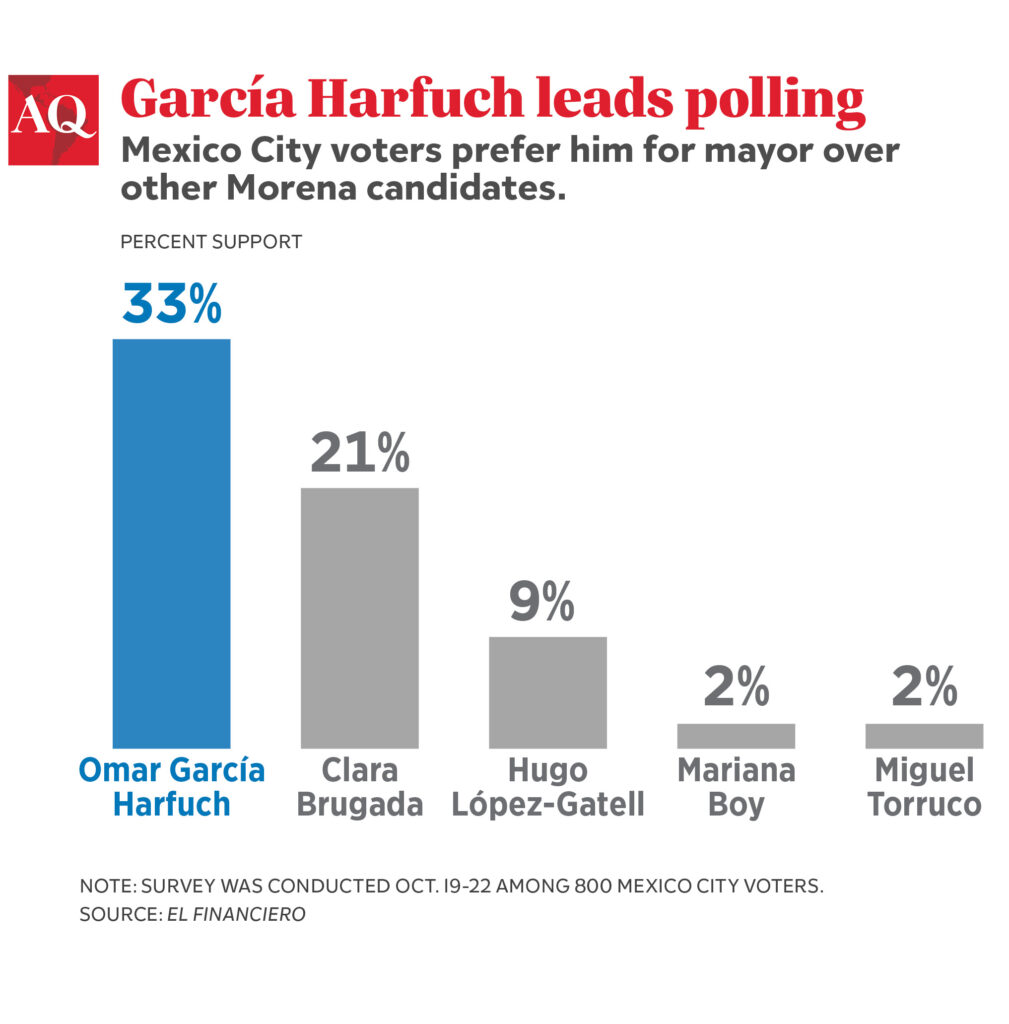

The city’s former security chief, García Harfuch, 41, leads polls and is a close ally of former Mayor Sheinbaum, now the presidential frontrunner and candidate for governing party Morena. Together, they slashed the city’s crime rates and became strong allies. But his background as an outsider to Morena’s leftist movement makes it uncertain that he will get the party’s nod, even though he is widely considered Sheinbaum’s preference.

His top rival is Brugada, 60, the former head of Mexico City’s most populated district and a loyal supporter of the movement of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, AMLO. With battle lines drawn, in October, over 800 Mexico City intellectuals signed a letter backing Brugada over García Harfuch. Public surveys put Brugada in second place. But even if García Harfuch does come out in front when Morena announces the results of its own internal polling process on Friday, a gender-parity rule could allow the party to set aside the results and give her the nomination.

The caped crusader

On a recent rainy night in Mexico City, a black-and-yellow Bat-signal lit up the iconic Monumento de la Revolución with a message across its bat wings: #EsHarfuch. García Harfuch’s backers compare him to Batman in part because of events that took place on June 26, 2020. As he traveled along Paseo de la Reforma, the capital’s most famous boulevard, hitmen linked to the Jalisco New Generation Cartel ambushed his vehicle. Two bodyguards and a bystander were killed. Garciá Harfuch took three of the more than 400 shots fired and, for many, became a figure willing to put his life on the line to combat organized crime.

And he has been effective on security. When Sheinbaum took office as mayor in 2018, the capital was facing rising violent crime rates. She put García Harfuch in charge of the city’s 88,000-strong police force, and, from 2019-22, Mexico City’s homicides dropped 43 percent to a rate of 8 per 100,000 inhabitants. (For comparison, Washington, D.C.’s rate was 29 per 100,000 last year.) “The sensation is that Mexico City is doing well at this moment. And that was achieved by Claudia Sheinbaum and Omar García Harfuch,” journalist and political analyst Salvador Camarena told AQ. With public safety is a top voter concern, this record is an asset. In El Financiero’s latest poll, García Harfuch stands 12 points above Brugada and 24 points ahead of AMLO’s controversial COVID-19 czar, Hugo López-Gatell.

García Harfuch’s party outsider status could also help Morena win back the middle-class voters it lost during the 2021 midterms. Should Sheinbaum and García Harfuch win, he would almost certainly remain a reliable ally; he has promised to continue her policies—security programs included.

A complicated history

But the Sheinbaum-García Harfuch alliance comes with a twist. “He became an atypical number two because he didn’t come from the [city’s leftist] movement, and because he represents a space that is rejected by and even cursed by this movement, and that’s the history of policing of our country,” Camarena said.

While Sheinbaum is a lifelong leftist whose parents were part of the 1968 student movement, García Harfuch’s grandfather, Marcelino García Barragán, was defense secretary during the infamous 1968 massacre of student protesters. And García Harfuch’s father, Javier García Paniagua, was a hardline power player in the once-hegemonic Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and led a federal police agency linked to dirty war abuses including torture during the 1970s.

García Harfuch himself was the federal police coordinator for the state of Guerrero when, in 2014, 43 students went missing there in the unresolved and still shocking Ayotzinapa case. Parents of the disappeared have called for an investigation into his involvement. He denies any connection, but questions about his role have stirred concerns about his policing career.

García Harfuch’s complicated past concerns many leftists in the country’s traditionally progressive capital, given that it would put him in line to run for president in 2030. “Twelve years after the great triumph of López Obrador in 2018 … the grandson of the general who represents the 1968 repression, the son of the director of a police force tied to the darkest moments of the PRI regime, could become the candidate of the left,” said Camarena, explaining progressives’ perspective. “You wouldn’t buy this plotline if it were in a novel.”

The other side

Brugada’s political career sprang from popular movements before she became a legislator and eventually went on to govern the working-class Iztapalapa district. While she was in office, Iztapalapa became home to the largest cable car in the Americas, some 7,000 street murals designed to transform the area, and a dozen largescale recreational and arts centers known as “utopias” that have earned UN recognition for combating inequality. When Morena suffered dramatic losses in the city in 2021, Brugada won reelection in her district by a landslide.

A recent ruling by Mexico’s electoral agency, the INE, further complicates the race. Due to a 2019 gender-parity reform, the INE ruled in October that political parties must nominate women in five of nine gubernatorial races, including Mexico City. In all nine entities, Morena’s candidate selection process involves three polls—one carried out by the party and two by private firms—to choose gubernatorial nominees. But the poll outcomes could be rejected to meet the INE parity guidelines. As parties scramble to conform, “there are states where it’s very clear who the final candidates are, but there are states where we have no idea,” said Fernanda García, a gender-issues expert at Mexico’s Institute for Competitiveness think tank.

Amid the confusion, Morena postponed its gubernatorial nominations from October 30 to November 10. Meanwhile, the divide in Morena’s coalition over the Mexico City competition has only gotten dirtier, adding intrigue to the presidential vote on June 2, 2024, as the city and the surrounding areas that form the Valley of Mexico are vital to the nation’s politics.

If García Harfuch is rejected in favor of Brugada, it would be Sheinbaum’s “first defeat” as the party’s presidential hopeful, Camarena told AQ. But Sheinbaum wouldn’t fight Brugada’s nomination, he said, because “she’s going to prioritize ensuring unity.”

For his part, García Harfuch would still be a top contender for a cabinet position if Sheinbaum wins the presidency. At that point, the question would be whether Morena loyalists will treat him as a hero—or a villain.

—

Zissis is editor-in-chief of AS/COA Online. She was based in Mexico City from 2013–21, during which time she covered, among other topics, the country’s 2018 elections.