CARACAS— An “a la carte” presidential election many had feared lies ahead for Venezuela after a contentious registration process ended with 13 candidates formally running. In a matter of days, the National Electoral Council green-lighted a slew of hopefuls but blocked the opposition Unitary Platform candidate Corina Yoris from participating in the contest. Yoris was the proxy candidate for María Corina Machado, the opposition’s most popular leader, who was herself banned.

Prominent among the long list of names is Manuel Rosales—founder of the political party Un Nuevo Tiempo, governor of Venezuela’s most populous state, and former presidential candidate—who is now distrusted by others in the opposition as a pro-system contender. His participation increases the uncertainties over this new chapter of Venezuela’s long-standing political crisis and creates a narrowing path for a political alliance to dislodge Maduro.

Rosales was the sole opposition candidate to compete against the late Hugo Chávez Frías in 2006, went into exile to Peru in 2009 under corruption accusations made by Chavismo, and came back to Venezuela in 2015. Shortly after his return, he was jailed in El Helicoide, the dictatorship’s most notorious political prison. Nevertheless, he was soon moved to house arrest and was released in 2016, when his ban from running for office was unexpectedly removed while others in the opposition were banned. Twice elected governor of the state of Zulia, he has national name recognition, and his party is a member of the Unitary Platform, which complicates the coalition’s position.

Still, he’s considered one of the “few members of the opposition who has a direct connection to Miraflores Palace,” the presidential residence in this capital, Madrid-based El Pais newspaper reported earlier this week. For many, the core issue is Rosales’s ambiguous position, sometimes more eager to criticize other sectors of the opposition than the regime itself.

That unpredictable stance raises the stakes on Venezuela’s already fragile political landscape. Beyond Rosales, the Unitary Platform has a placeholder candidate –former career diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia– who hopes it can replace Yoris. The clock is ticking, as the deadline for the final printing of candidates’ images on the ballot is April 20. The opposition can still change its candidate 10 days prior to the election, but his or her image won’t appear on the ballot, diminishing the chances of a successful run.

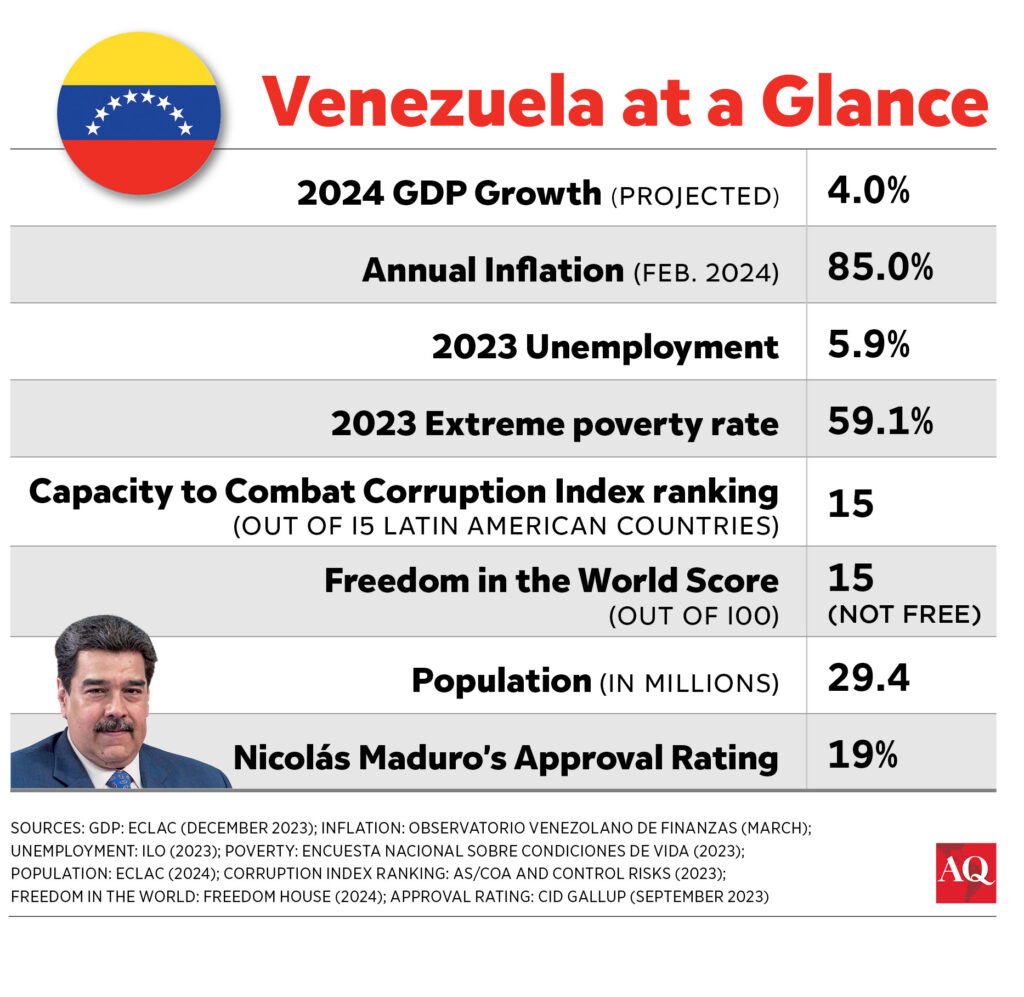

While Machado has hinted that Rosales’s registration for the election was a “betrayal” of the opposition, Rosales has reiterated in public events and interviews with local media his intention to endorse Machado should the electoral council later approve her candidacy. However, such a decision is all but ruled out, and a divided field of characters vying for the presidency simply increases the chances of a politician with a low approval rating, like Maduro, winning a third presidential term. Nevertheless, many in the coalition expect that the Rosales and Machado factions could achieve an agreement in the next four months.

Reflecting the international concerns over recent events in the country, earlier this week Colombian President Gustavo Petro blasted Maduro over the disqualification of Machado from the election as an “anti-democratic coup.” His comments are perceived as an unprecedented criticism from a leader who worked with Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva until weeks ago to create fair electoral conditions in Venezuela. “It was undoubtedly a way to shut out a real political current existing in Venezuela,” Petro added. “The people will determine whether it is a majority or not.” Additional condemnations from the U.S. and the European Union were all expected.

International observers

The arbitrary disqualification of candidacies and escalation of political repression in recent days raises concerns about the guarantees needed to ensure a transparent political competition ahead of the July 28 vote. In October, the government and the opposition signed the now-defunct Barbados accord, which provided for expanding the national electoral registry, permitting a freer press during the campaign, doing audits of the electoral system, and inviting foreign observation missions. But these points, meant to ensure free and fair elections, are all faltering, and will come under scrutiny in the days ahead.

“These are going to be the elections with the most restrictive conditions in the last twenty years,” Eugenio Martínez, a Caracas-based journalist and electoral expert, told AQ. Besides the restrictions, irregularities abound: While Venezuela’s electoral law states that the elections timetable must be published in its entirety in the electoral gazette as soon as the CNE calls for elections, the timetable has only been published as a set of dates in the CNE’s website. “Legally, there’s no electoral timetable,” Martínez added.

The electoral authority has invited delegations from the United Nations, the European Union, and the Carter Center to accompany the vote, but the invitations were sent in early March under a tight schedule. “This is clearly intended to prevent them from coming on time,” Gerardo Blyde—chief negotiator of the opposition’s Unitary Platform for the Barbados agreement—recently said in a radio interview. The European Union is expected to send a first exploratory mission to Venezuela this month, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it will have a complete observation mission deployed for the July contest, as a series of conditions and requisites are still needed. This schedule “makes the process difficult,” he added.

Local media reported that a delegation from Norway, a leading negotiations facilitator of late for Venezuela, has been in Caracas since April 2 for high-level meetings with the government, the opposition, and Machado.

Some rules

However, the regime has probably predetermined the outcome of the contest by scheduling the election on very short notice, pushing political parties and international organizations to race against the clock. The government has made 291 temporary registration points for new voters, scattered in sparsely populated areas, available only until April 16—Venezuela has 335 municipalities.

The more than 7 million Venezuelans living abroad the majority of whom would vote against Maduro – have been mostly excluded from this process. Despite protests from Venezuelan migrants, many embassies and consulates say they lack equipment or instructions from the CNE regarding a registration process from abroad. Only a few have started their electoral registration processes and are far behind schedule. Another point agreed upon in Barbados was freer electoral coverage for the press. However, the government has closed nine radio stations so far this year. Similarly, since 2018, the CNE hasn’t allowed questions at any of its press conferences

The CNE has also moved forward with scheduled audits of Venezuela’s automated electoral system’s software, hardware and databases. These include representatives from all political parties allowed to run, including the opposition coalition. “These processes give transparency to the technical aspects of the elections,” said José Huerta, the opposition’s representative in the audits. “When we have observed irregularities in other processes, like the 2017 Constituent Assembly elections, it’s because we didn’t participate in the audits.”

Against this backdrop, the Rosales-Machado relationship would be decisive, and nobody expects obstacles and repression to wind down in the next four months. While visiting Spain this week, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian A. Nichols expressed caution about Venezuela’s political outlook. “I would say at this time, the election doesn’t offer much hope,” he said, adding a veiled message to the ruling regime. “Nevertheless, there’s still time to change course.”

In Venezuela, where 80% say they are willing to vote, according to a recent survey by local pollster Delphos, not everyone is pessimistic: “Today I speak to you from the heart: We are right and we have the strength, we have the people, and we have a great opportunity,” Machado said on Easter Sunday, “Let us be confident that no one is going to derail us from the route that will lead us to clean and free elections.”

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify and other platforms

—

Michael Rendón also contributed to this story.