SANTIAGO—For the past several years, Ecuador has been in the international spotlight as it battles the brutal consequences of an aggressive expansion by organized crime and the growth of illegal markets. Drug trafficking is dominant, especially cocaine, thanks to the scale of international distribution routes to the United States, Europe and Asia—but other illegal activities, from logging to migrant smuggling and money laundering, are thriving too.

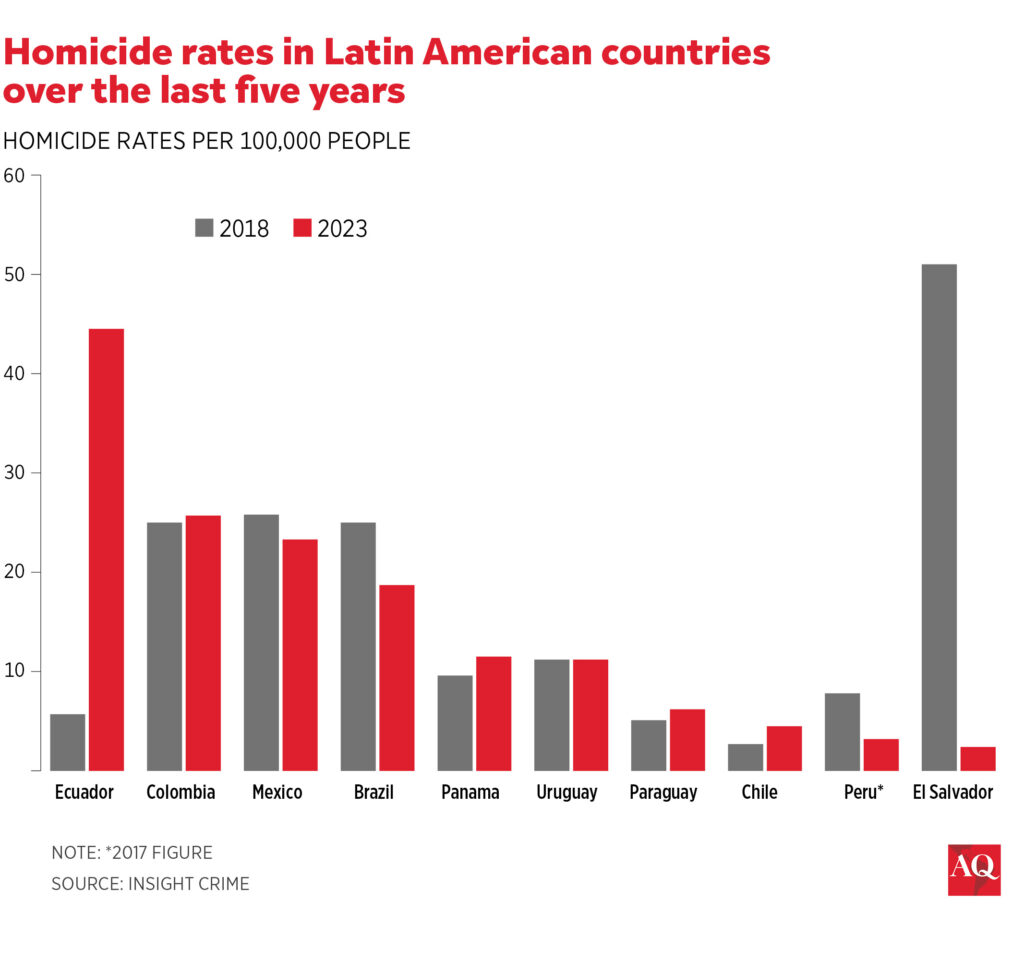

Ecuador’s crisis has been especially stark, but the problem of pervasive influence of organized crime is a regionwide one in Latin America. Many parts of contemporary Latin America see government failure to ensure citizen security and uphold the rule of law, especially for the underprivileged. From Mexico to Ecuador to Brazil, violence has surged in poor and precarious areas often neglected by governments, leading to neighborhoods and informal settlements falling under parallel criminal governance.

And it’s not merely a social or economic issue—at its core, it is deeply political. The entanglement of crime and politics has shaped the landscape of governance and public trust, posing significant challenges to stability and development in the region. The phrase, “It’s politics, stupid” captures the essence of this complex problem, underscoring the critical role of political dynamics in perpetuating and exacerbating illegal markets and organized crime.

Criminal organizations draw strength from many factors, not least of which is a strong and growing appetite for drugs in the developed world, but corruption, lack of transparency and fragile institutions at home provide fertile ground for them to flourish. In many countries, illegal markets have infiltrated politics as criminal groups influence elections to protect their operations—which not only undermines democratic processes but also erodes public trust in political institutions.

Several notable cases exemplify this phenomenon. In Panama, former Presidents Ricardo Martinelli and Juan Carlos Varela have been implicated in significant money laundering scandals. (Martinelli and Varela deny the allegations.) In Peru, a series of corruption scandals have engulfed multiple former presidents. Alejandro Toledo, Ollanta Humala, and Pedro Pablo Kuczynski have all faced legal troubles related to bribes from Odebrecht. (Each has denied the allegations.)

In Paraguay, former President Horacio Cartes has been sanctioned by the U.S. for significant corruption and money laundering, indicating the extent of his involvement in illegal financial activities. (Cartes denies the U.S. accusations.) Similarly, in El Salvador, former President Antonio Saca was convicted of embezzling and laundering hundreds of millions of dollars. Additionally, the cuellos blancos scandal in Peru and the “metastasis case” in Ecuador alleged involvement by judicial officials in various illegal markets, seeming to demonstrate the extent of criminal organizations’ infiltration of the justice system.

Trust is at a low ebb: The most recent LAPOP survey showed that in countries like Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Colombia, citizens profess little to no confidence that the justice system can punish criminals. (For good reason: the region has astonishingly high impunity rates, with only 24 homicide cases ending in convictions for every 100 homicide victims recorded—significantly lower than Asia’s 48 per 100 or Europe’s 81). In Peru and Nicaragua, nearly half of respondents said they would support a coup d’état to address security problems; in Ecuador, it was even higher, 57%.

Corruption scandals have hit members of the legislature in multiple countries, affecting not only their campaign financing processes but also the way laws are discussed and approved. At the local level, institutionalized corruption and collaboration with illegal and informal organizations has worsened, as these organizations provide security services, participate in public investment tenders and manage strategic areas of municipal work. Despite the prevalence of such entanglements, electoral punishment appears minimal, as many key figures involved in these scandals continue to be re-elected. When political systems become accustomed to receiving illicit funds in exchange for favors, the origin of these funds becomes irrelevant—especially as illegal markets develop various mechanisms for laundering money.

Fertile ground

It’s a general rule that institutional frailty hinders attempts to combat crime, and prisons are an especially stark example. States lacking control over penitentiary systems witness prisons becoming hubs of criminality, as in Ecuador, where gang leader Adolfo Macías Salazar, aka “El Fito,” escaped from a Guayaquil prison in January. But criminal control over prisons is widespread in the region. The “hyperinflation” of prison populations, combined with minimal investment in rehabilitation, infrastructure, and training, has created a critical situation, allowing criminal organizations to extend their power both within and outside prisons.

This situation highlights the need for comprehensive reforms in the justice and penitentiary systems, emphasizing data collection and institutional capacity-building.

Police forces, judicial systems, and other key institutions struggle with inefficiency and lack of resources. Moreover, the politicization of these institutions further erodes their credibility and effectiveness. Policymaking, in the absence of accurate data, often relies on intuition and past experiences, leading to ineffective and sometimes counterproductive measures. High impunity rates across the region—where only a fraction of homicide cases result in convictions—highlight systemic failures in the justice system. This ineffectiveness not only emboldens criminal organizations but also perpetuates a cycle of violence and lawlessness.

In the absence of robust data, policymakers face substantial challenges in adequately designing, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating security programs. Crime statistics are often inconsistent, insufficient, untimely, and not accessible to the public, resulting in data gaps that complicate policy design and implementation. Without high-quality data, it’s hard to comprehend the multifaceted factors influencing crime, forcing policymaking to rely on unreliable intuition and past experiences.

Addressing the political roots

To tackle illegal markets and organized crime, Latin American countries should address its political roots by strengthening democratic institutions, enhancing transparency and fostering political accountability. Anti-corruption measures must be prioritized, with stringent enforcement and independent oversight mechanisms. Building institutional capacity, particularly in law enforcement and the judiciary, is essential to restoring public trust and ensuring effective crime prevention and prosecution. Focusing only on police infrastructure, militarization of criminal deterrence and technological solutions will bring limited results.

Improving data collection and analysis is also vital. Reliable and timely data can inform more targeted and effective policymaking. Enhancing interagency cooperation and fostering regional collaboration can also help address the transnational nature of criminal networks. By recognizing and addressing the political dimensions of organized crime, Latin American countries can take meaningful steps towards breaking the cycle of violence and fostering a more secure and just society. Otherwise, the region risks treading a path that leads toward the construction of true mafia states.

—

Dammert is professor of international relations at the Universidad de Santiago de Chile.