Even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, economists at the World Bank, the IMF, and credit rating companies warned that many Latin American countries were facing daunting fiscal challenges. The alert followed a considerable surge in borrowing and debt-to-GDP ratios after unusually slow economic growth during 2012-19.

Worsening debt and interest burdens, it was cautioned, would limit governments’ ability to respond to potential new shocks. Unless economic growth accelerated markedly, fiscal restraint was warranted in nearly all countries. To make a meaningful and lasting difference, structural reforms in government spending and revenue streams were required.

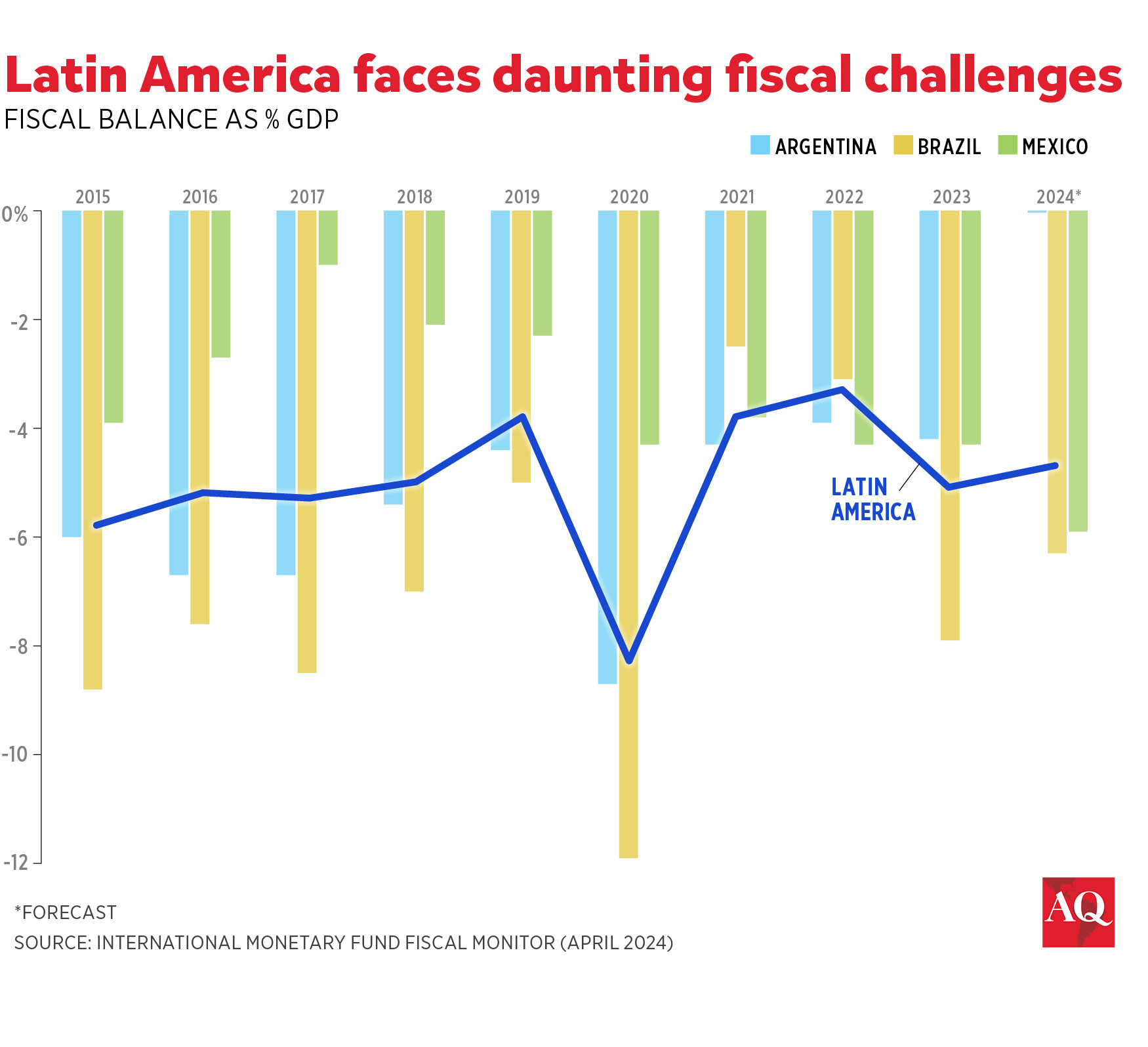

But then the pandemic arrived, and to support their economies and public health, most governments increased spending despite a decline in revenues, running even wider budget deficits. That entailed yet more borrowing, which led to heavier debt burdens. The combined regional fiscal deficit widened to 8.3% of GDP in 2020 from 3.8% in 2019, though one-third of that increase took place as the region’s GDP shrank 7%.

Fearing jeopardizing their future access to international capital markets, most governments in Latin America and the Caribbean reduced spending as revenues and GDP recovered and ran much smaller fiscal deficits in 2021 and 2022, averaging around 3.5% of GDP. In late 2022, forecasts were that fiscal prudence would continue and, thus, that budgetary imbalances would not widen again in 2023-24.

Nevertheless, the region’s fiscal deficits expanded again last year to 5.1% of GDP, and they are unlikely to narrow much this year except in Argentina, where a shock fiscal austerity experiment is underway. The regional deterioration was skewed by Brazil, where the fiscal deficit nearly tripled in 2023 to 7.9%. And there were some exceptions: in Colombia, the deficit narrowed significantly, and in Mexico, it remained unchanged.

Since governments are experiencing slow revenue growth and face higher borrowing costs, there is a new wave of concern in policy circles and financial markets, as prospects for this year’s fiscal outcomes are not looking good. The IMF’s credible forecast for Latin America is a combined fiscal deficit of 4.7% of GDP, marginally lower than last year’s, mainly due to an expected improvement in Brazil plus a potential deficit narrowing in Argentina worth four percentage points of its GDP.

Big countries, considerable tasks

In Argentina, the challenge is for the government to move from emergency spending cuts and payment delays enacted by executive decree to lasting spending reductions and revenue-raising measures approved by Congress. The latter have more legitimacy and are likely to prove more durable. Also needed are improvements in monetary, capital control, and exchange rate policies, as well as deregulatory and other initiatives that will enhance the investment climate.

The assignment in Brazil is to decelerate the growth of government spending as its public debt, equivalent to 86% of GDP, is among the most burdensome in emerging markets. Such restraint contradicts President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s election promises to boost welfare spending and expand the state’s role. During April-June, financial markets sounded alarms over the nation’s fiscal largesse because it prevents inflation expectations from converging to the central bank’s 3% target, thus forcing it to keep interest rates higher than otherwise. Fortunately, Lula relented earlier this month and agreed to some spending cuts, prompting a rally in beaten-down stocks, bonds and the currency.

Mexico’s President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum faces the unenviable task of fulfilling campaign pledges to expand social programs after her predecessor’s election-year spending spree. The 2024 fiscal deficit is forecast to reach 6% of GDP, up sharply from 4.3% in 2023—the widest deficit since the early 1980s.

Government expenditures in Mexico are currently equivalent to 30% of GDP, up from 25% pre-COVID. Spending on investment projects with low social returns, rising pension and interest payments, and substantial financial transfers to Pemex, the floundering state-owned oil company, are a growing concern. Since 2019, the outgoing administration has provided Pemex with over $50 billion, the equivalent of nearly 4% of average annual GDP. The company’s tax burden was reduced, and this year, the government is even picking up the tab for almost all its sizable debt repayments falling due.

Other countries disappoint

There are also fiscal concerns in several medium-sized and smaller nations. The pace of economic growth has slowed down sharply in the Andean countries: in Chile to 0.2% in 2023 from 2.1% in 2022; in Colombia to 0.6% from 7.3%; in Ecuador to 2.3% from 6.2%; and in Peru to -0.6% from 2.7%. These decelerations, mainly due to investment-unfriendly policies and/or political uncertainty, undermined their governments’ revenue base, jeopardizing their fiscal outcomes. Meaningful turnarounds are unlikely this year.

Panama, a relative success story during 2000-20, has become a concern because it is in danger of succumbing to economic problems that bedevil many other Latin American countries—including fiscal woes. Despite running a fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP last year and the authorities’ plans to bring it down further this year, Panama faces mostly downside risks. As drought has impaired shipping, earnings from the Panama Canal have fallen short, and so have revenues from a huge copper mine forced to shut down. In March, Fitch Ratings took away the government’s investment-grade rating, though Moody’s and S&P have not followed so far.

Implications

There are two main reasons why fiscal issues are taking center stage in policymaking and financial circles, a trend that also applies to many high-income economies, where budgetary deficits and public debts are running higher now than pre-pandemic projections foresaw. The reasons are the slower pace of economic—and thus of government revenue—growth, and the higher level of domestic and international interest rates—and, therefore, of borrowing costs.

Latin America’s annual economic growth during 2006-15 averaged 3%, but it dropped to a mere 0.5% between 2016-19 before undergoing pandemic-related swings from 2020 to 2022. The region’s GDP growth rate for 2023-25 is expected to average 2.3%, with correspondingly slower government revenue growth than in 2006-15. This alone justifies greater fiscal caution.

However, the compounding factor is the higher cost of borrowing. This rose by several percentage points in 2022-23 nearly everywhere worldwide and is coming down slightly this year. Moreover, chances are that interest rates in 2025-27 will not return to the extraordinarily low levels that prevailed before and during the pandemic. Many Latin American governments will likely have to keep paying meaningfully more for their new deficit funding, whether in domestic or international markets. In countries like Brazil and Mexico, where more than one-fifth of their indebtedness falls due each year, those higher costs are gradually being locked-in with each refinancing of short- or long-term debt.

With less favorable sovereign debt dynamics, particularly for the slowest-growing, more highly indebted, and/or deficit-prone countries in Latin America, policymakers and investors should stay increasingly focused on the region’s medium-term fiscal sustainability.