SÃO PAULO – Argentine President Alberto Fernández has declared a different type of war at home – a “war against inflation”. To fight this war, Argentina has implemented price controls and blocked exports of soybean meal and oil in an attempt to prevent “speculators” from reaping gains at the expense of higher prices for consumers. In Brazil, Congress rushed to cut taxes on fuel and cooking gas, and the government is mulling additional measures such as a temporary stipend for truckers, an increase in income transfers and even a change in fuel pricing policy to disconnect domestic fuel prices further from global prices.

The two countries’ strategies differ, but they both underscore the complex calculus of determining winners and losers in the context of war, especially when it comes to Latin American economies. The various economic impacts of the war – described Wednesday in Americas Quarterly by Martin Castellano – will have dramatic effects. So will the choices governments make in response. In many cases, policy responses may backfire, compounding risks and curbing potential gains.

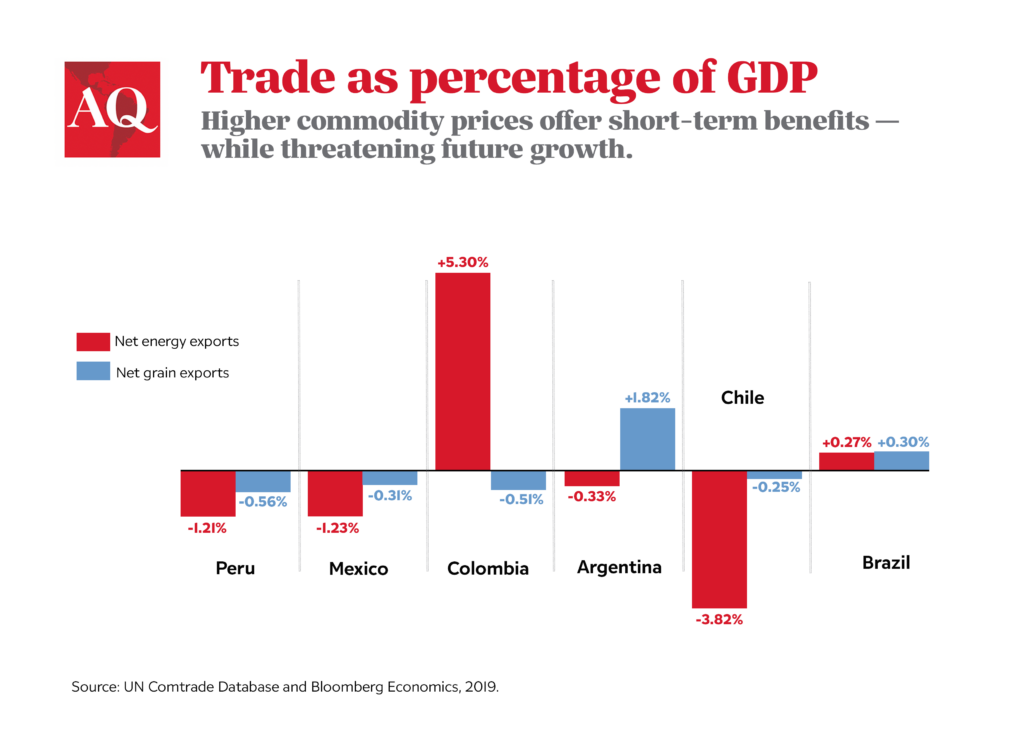

At first glance, Latin American economies might seem positioned to benefit, in strictly economic terms, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. All else being equal, higher commodity prices appear to favor the region’s exports. For example, a back-of-the-envelope estimate suggests that – should prices remain where they were at the close of the second week of war (+13% in energy and +10% in grains since the start of the conflict) – Colombia’s trade balance would see an annualized gain of 0.6% of GDP, while the trade surpluses of Argentina (0.2% of GDP) and Brazil (0.1% of GDP) would improve marginally. However, Chile’s trade balance would fall by 0.5% of GDP and Mexico’s and Peru’s would each fall by 0.2% of GDP.

These estimates focus on the direct impact of commodity prices on the trade balance, but the war changes other important variables. In addition to the human tragedy, the war represents a major setback for the world’s post-pandemic recovery. Bloomberg Economics estimates that the war will shave 1.1% off U.S. growth this year and may tip the European economy into a recession in 2022. Slower global growth means less demand for Latin American exports – so the windfall from higher prices may be partially offset by a decline in export volumes. Also, the key role of Russia and Belarus in the fertilizer market means that the agricultural sector may face a sharp rise in costs, not to mention the risk of supply chain disruptions.

If the trade gains are a possibility, the inflation pain is a given. The surge in international prices throws a wrench in what was already a challenging campaign to bring inflation back to target rates – which all major Latin American economies missed in 2021. Food and fuel – two of the most important items for consumer budgets – tend to follow international prices, with two possible offsetting factors. First, local currencies can magnify or mitigate the impact of a change in international prices. There’s some good news on that front; Latin American currencies have suffered, so far, limited contagion from the meltdown of the Russian ruble. This is consistent with their relatively low exposure to Russia and the positive correlation with commodity prices.

Second, governments may opt to cushion the impact of higher prices on consumers’ pockets with subsidies, tax cuts or income transfers (the path chosen by Brazil). That solution may be tempting, but most Latin American economies have little or no space to accommodate the fiscal costs. Finally, some countries may turn to the oft-tested, ever-failing strategy of price and export controls, ending up with high prices anyway, food and fuel scarcity, or both. This is the path Argentina has chosen.

Advanced economies may weather the war’s economic storm by postponing or slowing the increase in their interest rates, but emerging markets in general, and Latin American economies in particular, cannot afford that luxury. Most central banks in the region will meet war-driven inflationary pressures with additional rate hikes. Combined with depressed purchasing power for consumers and possible supply chain disruptions, the prospect of higher interest rates suggests that winds are becoming less favorable to growth in region, regardless of possible trade gains.

Dupita is Bloomberg’s Senior Economist covering Brazil and Argentina and holds an MSc in Economics from the London School of Economics. She is quoted often in international media, most recently on CNN Brasil.