There’s a reason why President Javier Milei seems like he’s in a hurry.

Even for a man who campaigned with a chainsaw to symbolize what he would do to the Argentine state, Milei has tried to implement a surprisingly ambitious array of reforms during his first month in office. Through decrees and an “omnibus” bill sent to Congress, Milei is pushing changes to more than 300 laws, the privatization of state-run enterprises, new restrictions on protests, and a broad deregulation of the environment, healthcare and labor laws.

This “maximalist strategy,” to borrow a term from the respected La Nación columnist Jorge Liotti, seems born from two contradictory facts.

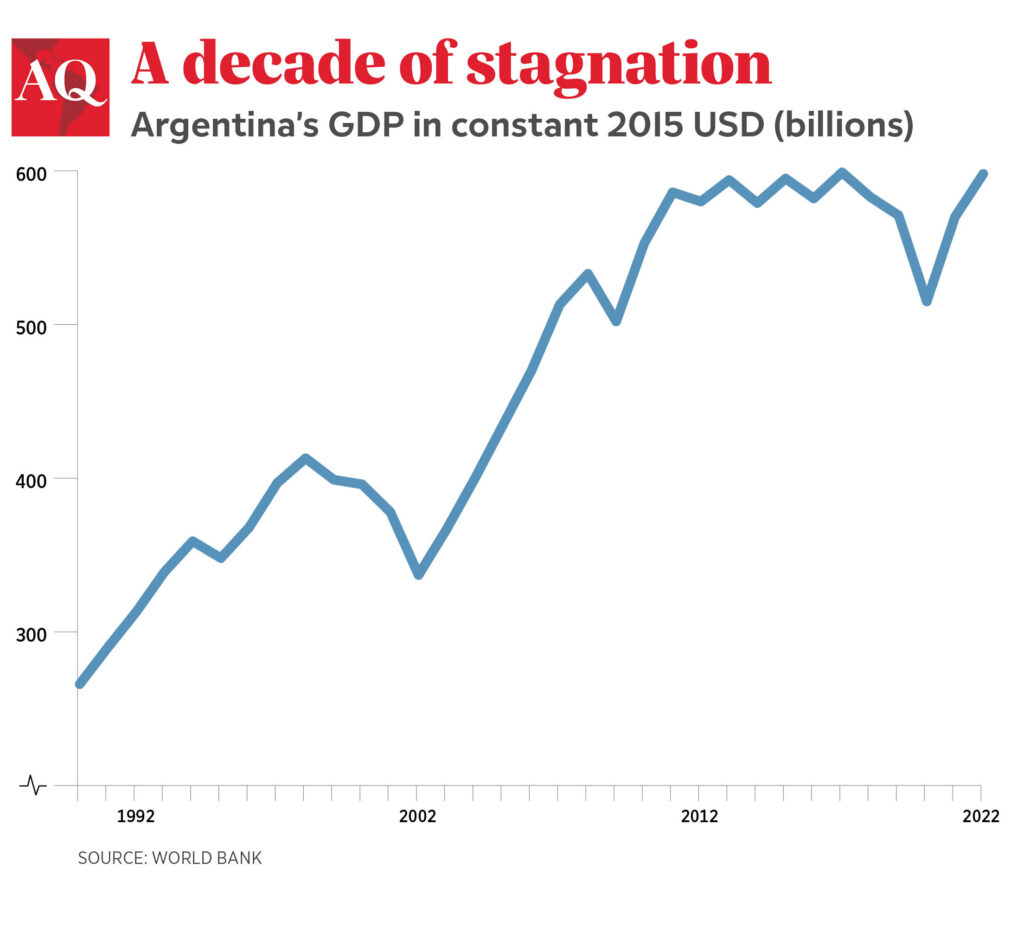

The first is that Milei is popular. Elected with 56% of the vote, recent polls suggest public support for his government remains high. Milei has a clear democratic mandate to slash Argentina’s public sector, which is one of Latin America’s largest and a main reason the economy has been stagnant or shrinking for most of the last decade. Milei has said the true size of the fiscal deficit is a stunning 15% of GDP (JP Morgan has cited a similar figure), a gap the previous government covered mostly by printing money, fueling inflation of about 200% a year and still rising.

Which brings us to the second fact: Milei will almost certainly lose popularity in coming months. His decision to devalue the peso by half and phase out price controls may bring long-term stability, but has pushed inflation higher for now: Prices probably rose more than 20% in December alone, the highest rate in 30 years. In coming weeks, his government is expected to begin increasing artificially low electricity and gas prices—just as Argentines return from summer holidays and the school year starts.

With so much pain ahead, Milei and his allies seem to have decided their window for action is relatively short.

“If by March or April the government can show results, and inflation starts to come down, that will be positive,” Liotti told me. “But if not, the social conflict could get intense.”

Everyone in Argentina knows what that could mean. The last serious attempt to reduce deficits erupted in 2001 in protests, riots and a carousel of five presidents in two weeks: a national trauma that I witnessed as a young reporter living in Buenos Aires, and that still looms large in the public imagination. Austerity is hard everywhere, but especially in a country with Argentina’s memories of faded wealth and countless failed stabilization programs over many decades.

Many Argentines today seem to recognize that sacrifice is needed; Milei’s unofficial slogan No hay plata (”There is no money”) has even been made into T-shirts and hats. Social welfare programs, which Milei has vowed not to cut, may do a better job protecting the poor compared to 20 years ago. Still, no one knows how much pain society is really willing to tolerate. The country’s leading labor union has already called a strike for January 24.

Milei’s “all or nothing” strategy is also under fire. Opposition leaders accuse him of trampling the Constitution. Even some non-Peronist politicians have criticized the government’s reliance on decrees, rather than going through Congress, where the president does not have a majority. For now, the government is insisting it will not negotiate, but some analysts expect that to change. “What I perceive are signs from Congress that this won’t pass, that Milei knows this, and he will protect what is essential,” Liotti said. “If the government gets even 70% of the bill, they’ll be satisfied.”

Given the political uncertainty, the atmosphere on Wall Street has been cautious. A vast majority of investors support efforts to reform an economy that, in a recent global ranking of competitiveness, put Argentina 63rd out of 64 countries, ahead of only Venezuela. Many have welcomed Milei’s apparent retreat from more radical proposals like dollarization, and hope he will reach an accommodation with the International Monetary Fund, with which Argentina has a $44 billion loan program. Argentina’s economy may be boosted in 2024 by a good harvest, new mining projects and continued growth at its enormous Vaca Muerta oil and gas field.

But I could find few economists who were willing to risk a forecast about when the government’s efforts might start to bear fruit. “Even if Argentina had a seasoned statesman at the helm, with ample political and executive experience … with majorities in Congress, and with a clear mandate for adjustment, it would be difficult given the fragile macro situation,” Ernesto Revilla, Citi’s chief economist for Latin America, told me via e-mail. Like many others, he will wait and see.

(with research by Emilie Sweigart)